An attempt by the owner of the private military company Wagner, Yevgeny Prigozhin, to march along with his soldiers to Moscow turned out to be unsuccessful, but it greatly undermined the prestige of Russian authorities. The Kremlin already knows how to deal with the so-called “liberal opposition”―mostly intellectuals and young students. But what about the rebellion of 25,000 well-armed criminals and mercenaries with combat experience? It seems that Moscow was not ready for this.

The first signals of the rebellion, in fact, appeared by the end of 2022, when Prigozhin began to speak critically about the senior command of the Russian armed forces, including Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu. He said the defence ministry was not providing ammunition to Wagner units in Ukraine. Prigozhin’s critical speeches culminated in a statement on June 23 in which he accused the Russian oligarchs and leaders of the armed forces of corruption, lack of professionalism and unwillingness to stop hostilities in Ukraine.

Prigozhin said Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky “was ready for negotiations” when Putin launched the military operations last year. He also blamed the Russian army for allegedly launching a missile strike on the Wagner units, which led to the death of about 30 fighters. As his troops started moving towards Moscow, he called it a “march of justice” to find out “why the country was in disorder”.

Rostov-on-Don, the million-plus city that houses the headquarters of Russia’s powerful Southern Military District, fell under Prigozhin’s control in a matter of hours. There were reports that the rebels also took Voronezh, a major logistics hub. Some of them even turned to the secret city of Voronezh-12, where Russia maintains a nuclear-weapon storage facility. Russian fighter jets stopped them from going there, but the rebels shot down some of them.

In Moscow, the authorities ordered a counter-terrorist operation regime. Mayor Sergey Sobyanin asked residents to stay indoors. Military vehicles appeared in the city centre and ordinary policemen were given machine guns. On the federal highways leading to Moscow from the south, checkpoints were hastily set up, while excavators smashed the asphalt, digging anti-tank ditches. Petrol prices went up and so did the cost of flying out to neighbouring countries like Turkey, Georgia, Armenia and Kazakhstan. Employers began instructing their staff to stock up water and other essentials. But it all ended abruptly as the Wagner forces, which were only about 200km from Moscow, stopped their advance and drove back. Prigozhin apparently reached a compromise with the Russian government through Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko.

The sudden uprising, however, showed how unstable the situation inside Russia was, even as the war in Ukraine continued unabated. When the war started, there were quite a lot of people who opposed it, but the authorities silenced them with repressive measures. However, by shutting them up, they allowed the emergence of another wing of the disaffected, called “angry patriots.” These are right-wing people who believe that the current Russian Federation is the heir to two empires―the Russian Empire, which collapsed in 1917, and the Soviet Union, which disintegrated in 1991. The Putin administration, which has been using the narrative that Ukraine―at least its eastern part―is an integral part of Russia, has become a hostage of the “angry patriots”. They want the hostilities to be intensified, including tactical nuclear strikes on Kyiv. They also want to keep Russia away from “unfriendly countries” and to subordinate the life of the entire state to one goal―to defeat Ukraine. And then, if necessary, restore by force Moscow’s influence in the Baltic states and other countries of the former Soviet bloc.

It seems that the authorities do not know what to do with “angry patriots”. While the opponents of the war were defamed as “agents of the accursed west” and “traitors to the motherland”, the same will not work with “angry patriots”. The Kremlin worries that Prigozhin could well become their leader.

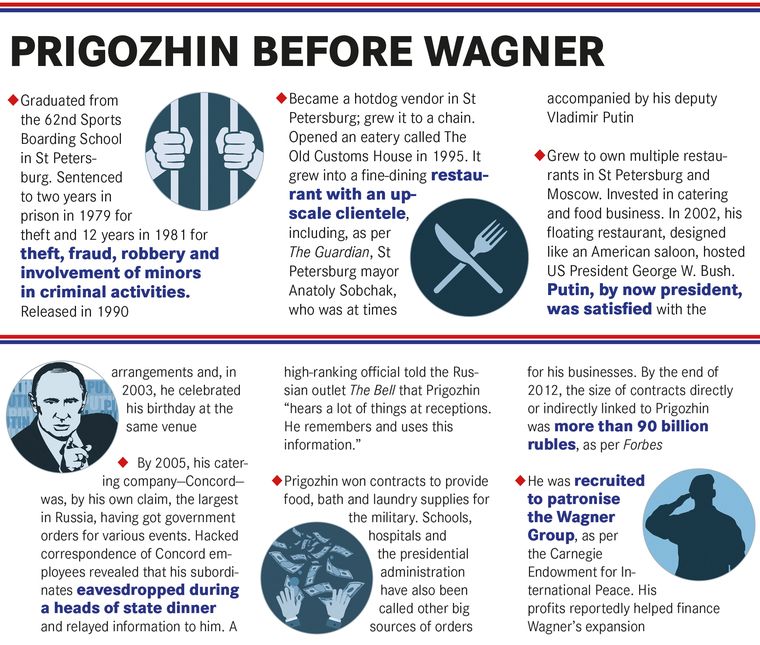

According to publicly available information, Prigozhin was convicted twice in his youth―for theft and fraud. He spent several years in prison, after which he started a restaurant business in his native Saint Petersburg. It was in his restaurant that President Putin met with the leaders of France and the United States in the early 2000s. Prigozhin gradually branched out into other areas such as construction, media and trade.

Prigozhin’s main business now seems to be leading the Wagner group, which was launched in 2014 to support Russia’s annexation of Crimea. It soon transformed into a full-fledged mercenary structure, playing an active role in global hotspots like Syria, Libya and the Central African Republic. Throughout 2022, when it became clear that Moscow’s plan to quickly “denazify and demilitarise” Ukraine could not be carried out, Prigozhin reportedly started visiting Russian prisons, recruiting prisoners for Wagner, which by that time had begun operating in eastern Ukraine. In exchange, the prisoners were offered pardon, the possibility of employment after demobilisation and even the possibility of studying in Russia’s leading educational institutions. They were paid about $1,300 a month and in case of fatalities, the families were paid more than $50,000.

Sudden retreat: Members of the Wagner group prepare to pull out from the Southern Military District headquarters | AFP

Sudden retreat: Members of the Wagner group prepare to pull out from the Southern Military District headquarters | AFP

Wagner units took part in the most difficult battles, including the one for the city of Bakhmut in eastern Ukraine. At the same time, Prigozhin, in the style of the “angry patriots”, wanted Russia to be made a wartime economy, called for the return of the children of Russian officials and oligarchs from abroad, asked for the borders to be closed and demanded the reinstatement of death penalty. As a result, when Prigozhin launched his rebellion, he was opposed not just by the government, but also by most of the opposition that adheres to liberal views. If the opposition cursed Putin earlier, the president suddenly turned out to be the guarantor of order following Prigozhin’s threat. The only exception, perhaps, was oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who lives in exile and is bitterly anti-Putin. He sought support for Prigozhin in the hope of capitalising on the rebellion.

Although Putin was able to defuse the crisis quickly, the “justice march” showed that the government was unable to respond quickly to a serious threat. It is clear that the Wagner military columns would hardly have been able to enter Moscow unhindered, but an open fight between the Russian army and a private military company on the outskirts of the capital would have caused panic across Russia.

Equally concerning was the reaction of the residents of Rostov-on-Don, who greeted the Wagner mercenaries with flowers, which showed that many Russians sympathised with the “search for justice”. In Russia, the idea of justice has always been extremely popular among common people. The bloody riots of people’s leaders Stenka Razin in the 17th century and Yemelyan Pugachev in the 18th century attracted huge support. In both cases, the authorities had to organise full-fledged army operations to suppress the rebels. This thirst for justice has not disappeared completely. The only difference is that now the rebels have missiles and tanks, and could even appropriate nuclear weapons. Moreover, Russia has a large group of people connected with crime, and many of them are in prison. They consider Prigozhin as one of their own and they understand him quite well. If an opportunity presents itself, they will follow him.

The multiple U-turns of the Russian government has, meanwhile, hurt its image. On the afternoon of June 24, Prigozhin and the participants in his march were branded “traitors”. A criminal case was filed against him for inciting rebellion. Putin called Wagner’s actions “treason”, threatening the rebels “inevitable punishment”. But, in the end, there were no traitors. All charges were withdrawn and the criminal case against Prigozhin was closed. It made many Russian citizens unhappy as Wagner had, indeed, tried to start a civil war and betrayed the homeland at a difficult moment, but was quickly forgiven. The Kremlin was forced to compromise as it realised that the niche of the “front-line hero” was empty in today’s Russia. Prigozhin can possibly claim that space as “a tough guy who really fights while the professional military is busy with who knows what”. He has a chance to become a “people’s leader”, albeit with a criminal past.

Prigozhin is now in Belarus. While some of the group’s fighters are moving there, the rest are either going to serve in the Russian army or end their military careers. Most observers believe that Wagner will return to Africa and the Middle East, where they will continue to perform a variety of tasks.

In Russia, the authorities have tightened control in order to prevent new rebellions. It can be expected that there will be no new armed uprisings in the near future. However, the questions that Prigozhin raised―about Russia falling short in Ukraine and who is to blame for the problems of its army―remain. And they continue to remain a major headache for Putin.