ON OCTOBER 3, PAKISTAN Interior Minister Sarfraz Bugti announced that illegal immigrants in the country should leave by November 1. The caretaker government warned that they would be deported, if they failed to comply. The order has hit unregistered immigrants from Afghanistan the hardest, forcing the United Nations to weigh in. Said Qaiser Khan Afridi, spokesperson for the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “We have seen disconcerting press reports about a plan to deport undocumented Afghans and we are seeking clarity from our government partners. Any refugee return must be voluntary and without any pressure to ensure protection for those seeking safety.”

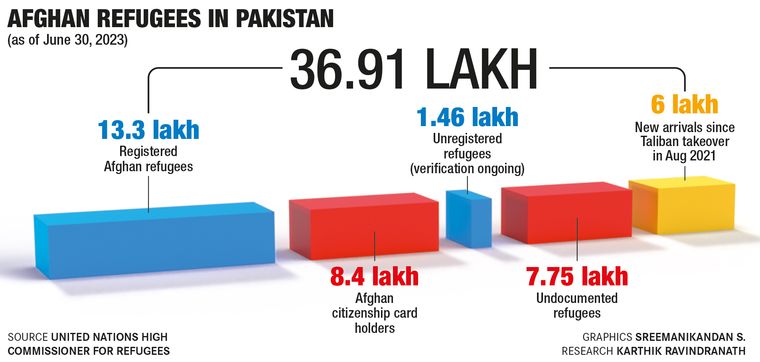

Since the move has been seen as targeting Afghan migrants who number around 37 lakh, Pakistan’s foreign office clarified that the order applied to all foreigners without valid documents. A foreign office spokesperson said Pakistan’s policy towards Afghan refugees “remained unchanged” and the ongoing operation was against individuals who had either overstayed their visas or did not have valid documents. Pakistan has hosted millions of Afghan refugees since the Soviet Union’s invasion in 1979.

There are about four types of Afghan refugees, according to journalist Azaz Syed. The first category has been in the country since the time of the Soviet invasion. A lot of them still remain undocumented despite the group being in Pakistan for at least three generations. The second group got themselves registered in 2007, and got a document called proof of registration (PoR). This was done with the help of the UNHCR. The third category comprises people who registered in 2017 through the Afghan Citizen Card (ACC). Those with the PoR and ACC number around 22 lakh.

The fourth category, numbering around seven lakh, came to Pakistan after the fall of Kabul to the Taliban in August 2021. Most of them are in ‘transit’, as they want to leave for a third country. They are spread across cities such as Islamabad, Peshawar, Lahore and Karachi. The UNHCR and some countries are supporting them. “A large number of Afghans have become an integral part of Pakistani society. Some of them have also sneaked into the system and got Pakistani citizenship and passports,” said Syed.

A distressing situation has unfolded in Karachi, where over a thousand Afghan refugees were arrested by the local police, said Moniza Kakar, a lawyer. “Police say they are undocumented, but a majority of them possess valid identification cards,” said Kakar. “The wrongful arrests and detention of documented refugees have raised serious humanitarian concerns. These individuals have fled from conflict and instability in Afghanistan, seeking refuge and safety. Their unjust incarceration not only puts their wellbeing at risk, but also highlights the need for a closer examination of the situation.”

Uncertain future: An Afghan family waiting at the Torkham border in Pakistan to return to Afghanistan | Reuters

Uncertain future: An Afghan family waiting at the Torkham border in Pakistan to return to Afghanistan | Reuters

Aman Ullah, a PoR card holder, told THE WEEK that after the announcement about illegal immigrants was made, even PoR card holders were not spared. Often, their cards are snatched and destroyed by the police. “Wherever the police see an Afghan, it happens. More than 2,000 Afghans with PoR or ACC cards are in jail, apart from those who do not have papers. Afghans are worried and are going back home,” he said. “Things have improved a little after the interior minister’s announcement that seized identity documents should be returned. Some courts in Karachi have given relief to card holders, but others have not. Those Afghans who have businesses like restaurants in Karachi are being told by building owners to vacate.” Most Afghans are scared to venture out of their homes.

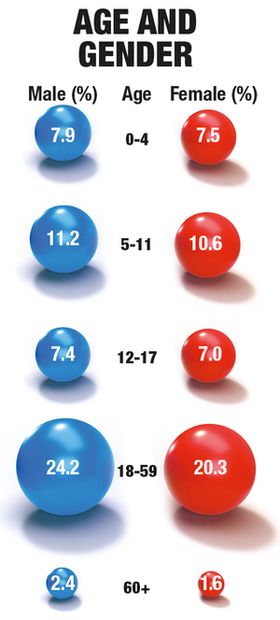

“Refugees fleeing war and turmoil have a moral right to seek refuge in another country and to be treated with dignity and empathy,” said Harris Khalique, secretary general of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan. He said the HRCP was lobbying the government to reverse the blanket decision to ban all migrants, as it would affect vulnerable groups, including women and children.

Khushal Khattak of the National Democratic Movement (NDM), a Pashtun nationalist political party, told THE WEEK that following the caretaker government’s announcement, Afghans were arrested in hundreds and raids were being conducted in their places. “This is why it seems that this is directed at the Afghans.” And, in the case of valid document holders, many of them are let off after bribes are paid. In recent weeks, some Afghan settlements in Islamabad have been razed. “These are poor people. There is also a fear within the Afghan community that if they are arrested, the bail process is very problematic and difficult,” said Khattak.

NDM chairperson Mohsin Dawar introduced a bill for the protection of refugees, but it was not allowed to be on the agenda. “There is a lot of uncertainty and fear within the Afghan community. Human rights activists and Pashtun parties are talking about it. Unfortunately, mainstream voices are missing,” said Khattak. “There is a danger to some of these Afghans from the Afghan Taliban and it would be difficult for them to go back. Also, there is no state in Afghanistan at the moment. What are they supposed to return to? This is a humanitarian crisis. There needs to be more voices so that the government reconsiders this policy.”

Former lawmaker and senior politician Bushra Gohar said the Afghans were being forced out because of the Doha deal between the US and its allies and the Taliban. “The unending cycle of pain and suffering of the displaced Afghans has been exacerbated by Pakistan’s caretaker government with its announcement of forced eviction and deportation. Giving a deadline to leave and threatening to check DNAs of Afghans is meant to add to their sufferings and is in violation of human rights.” She said it was not the first time that such knee-jerk reactions had been taken by the government against vulnerable Afghan refugees to divert attention from its failed Afghan policies.

“Those who came much earlier and have legal documents are also facing harassment and extortion. Homes in Kutchi (an Afghan nomadic group) settlements have been razed before the announced deadline. Such reactions are in violation of universal human rights and international conventions. Pakistan with a large refugee population does not have a coherent policy and law for refugees. A private member bill was tabled in the previous National Assembly but it was obstructed and not allowed to be debated,” said Gohar. She asked the government to facilitate registration of families, especially women and children forced to leave Afghanistan to avoid persecution by the Taliban. Gohar said terrorising the vulnerable Afghan population to build pressure on the Taliban must end. “Finally, it is not the mandate of caretaker governments to take such policy decisions with serious human rights, security and foreign policy implications.”

Zebunnisa Burki, a senior journalist who focuses on humanitarian issues, said it would be cruel to send back scores of refugees to a country devastated not just by war, but also by a regime that did not care for its people. She also spoke about the devastation caused by the recent earthquake and the impact of the western sanctions. “Why are we sending them back now? If the government wants to crack down on smuggling and other activities, it should be done, but sending the Afghan refugees back by giving them a deadline is sheer cruelty.”

The government, however, pushed back at the criticism. Interior Minister Bugti told THE WEEK that the new policy was not specifically against Afghans. “It is not aimed at any specific ethnic group or any specific country,” he said. “Anyone who is here with a refugee status or a transit status are our guests. We are only asking illegal immigrants―those who have illegal businesses here, those who have breached our security data to make illegal identity cards, be it Afghans or people of any other nationality―to leave.”