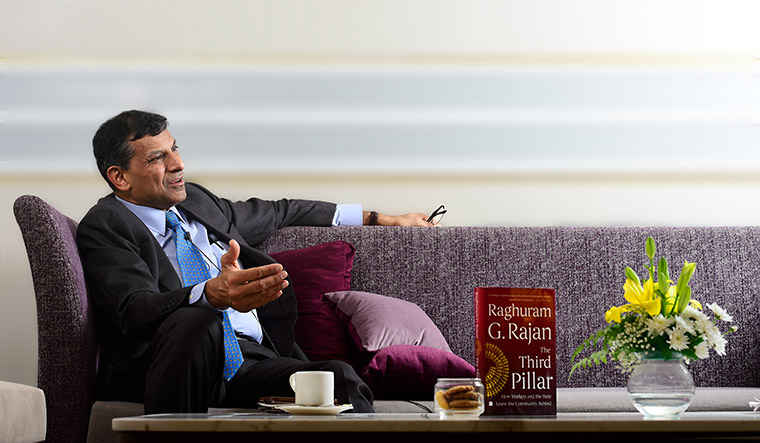

Raghuram Rajan says he has no interest in entering politics, but his latest book, The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind, is as political as it can get. The highly readable book, published by HarperCollins, is more than economics—it is about people and how their lives are impacted as governments and markets grow strong, and how technology can be both villain and hero. While references to political parties are made just in passing, the ideological discussion is in great breadth and depth, and it makes no secret of what in his view is good for the economy and society.

The Katherine Dusak Miller Distinguished Service Professor of Finance at the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago, Rajan seems a totally political being with an ideology on the table. And the timing of the book launch is also interesting, as India is preparing to vote for the Lok Sabha. Rajan has been doing television interviews and presentations to packed halls. And his unambiguity and logic have definitely rattled the right wing in India. He says he has an open mind when it comes to public service, but draws a clear distinction between politics and public service. Excerpts from an interview:

“Populist nationalism will undermine the liberal market democratic system that has brought developed countries the prosperity they enjoy.” Can we illustrate or estimate the damage on account of this?

In the book I talk about populism as having healthy elements to it because it raises the right questions. Populism is often the revolt against the elite. It is saying we the people think you are not doing enough for us. Because it raises the right questions, I think there is an element of value to those kinds of movements.

My worry is they sometimes take the wrong direction, and are often supported by people who are very disgusted with the existing system because they feel the elite support the immigrants, they support too many minorities, they are not really looking after the majority community. That is what populist nationalists do.

There are other forms of populism we can go into, but the broader point I am trying to make is that the problem with populist nationalism is that it may highlight the problems with the elite policies, which is not a bad thing, but its solutions often involve very protectionist or narrow policies. We are going to help the majority by removing any protection the minority has or we are going to stop migrants from coming in, we are going to erect trade barriers with other countries. Essentially these are very myopic solutions and do not lend to a long-term sustainable answer.

You have written about the aspirational young not getting the right kind of education. That reflects on the RTE, the school education reforms.

I am not an expert in education, but what I understand about the RTE is, on the one hand we have made progress in getting almost everybody into school at an early age. The problem is they do not stay in school. And it may well be that elements in our education policy are contributing to that. Because kids need to be at a level commensurate with the level of the class, if they are to continue learning. Because teachers are teaching to the level in the class. If a child falls behind but is promoted regardless, the child is not only going to be unable to understand the material for the previous class but is also totally unprepared for the next class. So the level of incomprehension of the child will just continue to increase.

One of the elements of our policy today is ‘no holding children back’; the way that works is only if you offer significant remedial education for the children who are weak. If you do not bring them up to the class level, what you are ensuring is that they fall further and further behind. I think some of the evidence from the Pratham or the ASER surveys suggest that our children are not doing well. Many in the eighth grade cannot read fifth grade level; they cannot do third grade level math. Our system is not working well. We need to really think about how much of this is because of our current policies.

Will populist nationalists retract from their mission of remaking the country in their image?

I think that path, if taken, is very dangerous for the world, because it is not a path that encourages significant dialogue between countries and within the country it creates the possibility of social conflict. So I would hope that it is a path than can be put back, that we can contain the impulse for populist nationalism and make it a much more decent populist nationalism, if you want to go there, but not the aggressive populist nationalism that we see.

For that I think we need an understanding of why it emerges and is pushed back by the other forces; a pushback by essentially dealing with the causes of the populist nationalism at its roots. And that is why the book is about explaining why we get to these kind of situations, what is it about our economies that push us into politics of anger and how do we alleviate those policies.

How do you see the journey from globalism to nationalism to inclusive localism panning out for India?

I think we are already in the process. In colonial times, because we were ruled by a small group of Englishmen from Delhi, essentially there was a lot more centralisation and we continued that over the first few years of the republic. Since the early 1990s we thought maybe we have centralised too much, let us decentralise so that people get control and they can actually do things. We started with panchayati raj, but there is still some way to go. Many of our municipalities, many of our mayorships do not have enough power. They are almost ceremonial positions. Some of our panchayats are not empowered with a lot of funding. So, you can elect the sarpanch but the sarpanch does not have much to do that affects the lives of people, and there is much to do. They do not have local schools, they do not have control over the local PHC (primary health centre). So what we need to think about is how we can empower people more, give them a sense of engagement so that they can address their problems. That is why I say empower the community more by pushing down power from the national to the regional to the local.

We have been seeing a lot of announcements in the nature of safety nets.

Well, it is something we have to be conscious of and avoid. That is why it seems to me that costing out the kind of promises we make, and to see whether in the long run the benefits will outweigh the cost and we can pay for it, is very important. To some extent, when we make income transfers to a particular segment of the population, the hope is that we give them enough of a support that they come out of whatever situation they are in, whether it is poverty or agricultural distress, and they can start generating sufficient income down the line. That kind of an idea, if it works, can pay for itself. But, in the longer run, if they do not come out of it and become fully productive citizens, and continue absorbing these kind of flows, you have to worry, whether in fact you have overburdened the fiscal system. Then you have to ask yourself whether we can afford this any longer. So, every kind of fiscal support you give should be assessed—is this sustainable in the long run. And to the end that it improves the capability of the targets. They may earn enough to pay back some of the support and more. It is a good thing then.

It is election time in India, and it rains promises.

This goes back to the time when we make the promises, the degree to which we scrutinise them. So what is important going forward is that we have a kind of fiscal commission of outsiders to the government who opine on the kind of policies that the government is proposing—this pension scheme, that transfer scheme and all these. It looks at the cost you are raising and the revenues. It looks at both and asks—is this feasible, is this viable? And to the extent that if the fiscal commission does not think it is viable, it puts pressure on the government to rectify these. That is a good thing. It keeps us from getting into trouble, from making promises that we cannot keep.

We used to hear the mandarins of North Block and South Block say India is a sweet spot. But no longer now.

One of the surveys I saw recently, by Prof Trilochan Sastry at IIM Bangalore and Prateek Raj, a colleague of his who used to be at the University of Chicago, is on 2.7 lakh voters going into these elections, asking them what are your major concerns. The number one concern is jobs. Are there jobs? Are there likely to be good jobs for us? And when you say we are not hearing about the population dividend, the population dividend is a dividend only if the people coming into the workforce thinking they will get jobs. If the anxiety reflects the difficulty of getting jobs, then the dividend is at best neutral and at worst can turn into a curse, because what you have is people who cannot get jobs essentially getting angry.

How damaging would the aggression of the right wing behaviour be to the markets?

I think the low-level conflict can be handled. I would not worry about that. We are a country that has always had some low-level issues in different states. What could be more worrisome is some very strong movements, mass movements to achieve a particular goal—let us try and ease these people out of the positions; let us keep the jobs for those people; let us erect strong barriers against inflow of goods through trade. If you take more dramatic action because you feel you have the mandate of the people, then we can get into more severe problems. Otherwise it is handleable.

You named the RSS in the context of populist nationalism.

The RSS is one example of a populist nationalist organisation, and the book is largely against the aims of the populist nationalist organisations. The RSS counts as one of the problems. There are good people in every organisation. There have been very very honourable and praiseworthy [RSS] members like Atal Bihari Vajpayee, a very decent human being and a great leader. But that said, the organisational aim is imposing a sort of a view on everyone else, a view which is much narrower than the broad syncretic country we have become, and that to my mind is counter to the view of India as embedded in the views of our founding fathers like Jawaharlal Nehru and Gandhi as well as in the Constitution. So, to that extent, I believe it is a much narrower view and because of this it does not give as much freedom of participation in the broad stream of Indian life to a variety of communities outside the majoritarian community and others that it considers part of the majority. That to my mind is deeply problematic for an open democratic country like ours. We cannot afford it, and so long as they do not fulfil their aims it is fine. But they are a very powerful organisation. And they are working towards fulfilling their aim. I dispute that aim.

Will Indian voters be able to distinguish between their view, the impact it can have on society, and the development agenda?

I think the voter is far smarter than we give him credit for. They understand a good development agenda of some of these organisations and some good nationalistic work done in times of calamities. But when the other, more divisive side, takes over, the voter knows this is the downside and can react to that.

Electoral bonds are within the purview of the RBI. It has reached the Supreme Court.

There are multiple aspects to it. The safety and soundness aspect. It is just a way of transferring money from a donor to a political party. There is no safety and soundness, it seems to me, embedded in that bond.

The second issue for somebody like the RBI is, do I know whether this is clean money or not. Because of the murkiness of the origins, the bank that gets the money is supposed to check. What I am not sure about is whether there are enough checks to see if the money is relatively clean. I think there are checks in place, but I am not familiar with them.

But where I understand the Election Commission is unhappy is that it reduces the transparency of the election funding process. You have no idea of who is giving it to the party receiving it. Many election issues are about transparency. If I know who is paying that party, I know the aims behind it, and then I can make an informed decision as a voter. This non-transparency about who gave the money will make the funding much less clear. So I would take the Election Commission’s concern seriously.

You are popular. Do you see a political role for yourself?

I think you are popular until you enter politics. Then you become unpopular. That is why I have no interest in entering this. I have no interest in becoming a politician.

The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind

Author: Raghuram G. Rajan

Publisher: HarperCollins

Pages: 434; Price: Rs799