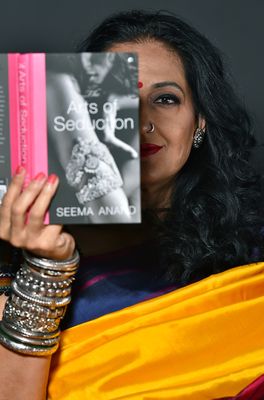

While many authors are discovering the Kamasutra’s non-sex content, Seema Anand—author, mythologist and narrative practitioner—says there is a lot to celebrate about sex in the ancient treatise. An authority on eastern erotology and tantric philosophy who uses the title Kamadevika, instead of Ms or Mrs, the London-based storyteller considers the Kamasutra the first book to place women on an equal footing with men. She views it as an incredible narrative of diplomacy and a brilliant lesson on language—there is no coarse or abusive language in the book, in contrast to today’s abusive vocabulary around the sexual act. Her book, The Arts of Seduction, published in June 2018, is a guide to having great sex in the 21st century. Excerpts from an interview:

Suddenly there is a lot of Kamasutra all over the place. Are we rediscovering ancient Indian erotica?

For a nation that ‘doesn’t talk about sex’, we seem to be focusing a lot on it in recent times.

I think it has more to do with how utterly dysfunctional our sexual attitudes have become and the kind of violence and aggression and ugliness it is leading to. We Indians live in a twilight zone of sexual attitudes. For centuries we have grown up with schools teaching sex is bad, sinful, evil. That is the front-of-brain, conscious thought.

My teacher at boarding school—I was six years old at the time and yet I remember this so clearly—told me, ‘Only fast girls enjoy sex’. I didn’t know what a ‘fast girl’ was. You can understand how we’re trained to think about sex. It’s a sin and it is so deeply ingrained that each time we ‘do’ it, we feel we have done wrong. Is it any surprise that we react to it with ugliness?

But we also have the Kamasutra factor, a subconscious DNA memory that talks of sex as a thing of pleasure and beauty, a thing of divinity even. I think our return to the work of Vatsyayan is a subconscious effort to try and change the ingrained attitudes.

The Kamasutra is the most beautiful, elegant and refined of all erotic writings. It inspired the poets of India—Kalidasa, Bhanu Datta, Bihari—to write epic romances. It laid the foundation for the most civilised of societies, a thing that we have not known ever since.

Our sexuality is an inherent part of our psyche; it is the core of our being. Maybe, we are all trying to dig deeper into our subconscious and understand ourselves better. Maybe, we have realised that there is more to sex than sin and evil—or at least I hope we have.

Is this rediscovery of the Kamasutra a reflection on our moral policing and our resistance to the feminist movement? A reminder that ancient India had very liberal attitudes towards women’s sexual freedom?

There is certainly a conscious ‘Kamasutra branding’ going on. A jingoistic “Look, we were such a liberal society thousands of years ago when the west couldn’t even be called a society.” But I would like to think that it is representative of the new identity that women are working towards.

For a long time ‘pleasure’ has been a male privilege—the woman’s duty was to please, and in pleasing her man, she would experience pleasure. The taking away of a woman’s right to pleasure is what has reduced the sexual act to nothing more than a quick involuntary ejaculation that most people mistake for an orgasm. Result: There is no real ‘pleasure’ for anyone; not for the man and definitely not for the woman. And if, as a result, a woman found herself turning off sex, then ‘she was frigid’.

Then came the studies that told us how women had voracious sexual appetites and could have as many as 40 orgasms at a time—another thing to add to male fantasies. It will take decades to get the point across that women don’t ‘come to’ multiple orgasms—they have to be ‘brought to’ multiple orgasms. There is no button you can press to make the woman come; there isn’t even a little blue pill with which to arouse her. It is up to her partner to bring her to excitement; it takes time and effort!

But changing economic and academic circumstances are bringing a new independence for women. And, with it, women are finding their voices and coming to a better understanding of their own feelings and desires. Things are changing.

Sex should be about pleasure, for all parties concerned. The Kamasutra is about pleasure. It is not about having children or ‘duty’ in any form—just pleasure at its most elevated and refined avatar, worthy of divinity.

In the era of the world wide web, what makes the Kamasutra a timeless book?

The Kamasutra comes with a sort of mystique. It represents a fantasy that is beyond any kind of articulation that would have surprised Vatsyayan.

Because most people actually do not know what the text is about—everyone has built up their own ideas around it—in its own weird way, the Kamasutra encompasses everyone’s fantasies.

The book has a global identity. Mention Kamasutra, and everyone smiles a quiet little smile; they know it is a book about sex. And not just sex, but [because of the years of mistranslations and misrepresentations] wild sex and crazy positions. Which is quite ironical because the book is extremely sensible, almost to the point of being prosaic. And other than a couple of extremely strange positions which really don’t make any sense at all, the positions are useful, practical and even medicinal.

The language is archaic and the references so obsolete that very little of it makes sense to the average person, which is probably why no one really reads it, and so it has come to be represented by its lowest common denominator—a sexual fantasy that is beyond anything that anyone can actually do or see; it is that innermost arousal that has to remain in the imagination.

For me the Kamasutra has a lot of agency. If we could get people to really understand what it stands for—the gender balance, the acknowledgment of women, the narrative of refinement and beauty, the distinct lack of misogyny and violence, the fact that it refined the art of loving and lovemaking to such heights of elegance that it inspired the poets of ancient India to write epic romances for the next 2,000 years—I think people would consciously want to keep the book alive and relevant.

But in the meantime, if the misconceptions are what it takes, then so be it. So long as it stays paramount in everyone’s minds as the text on sexual activity at some point, its message will come through.

What made you write The Arts of Seduction? Did you write it for Indians of a particular age or were you targeting people the world over?

I am fascinated by the literary and cultural heritage of the Kamasutra which is all but lost to us. This is the book that inspired Sanskrit and Tamil classics—prabhandhams (epic romances) and padams (poetry of the lotus foot). This is the book that created the traditions and metaphors of sensuality and pleasure that went on to inform the vocabulary, arts and practices of ancient and medieval India.

What did it mean, for instance, when in Kalidasa’s Kumarasambhavam the bride’s handmaidens, having perfumed and painted her feet (for her wedding night), giggle and whisper, ‘Now let’s see how he (the groom) places these to his head’? Why should he be placing her feet on his head? Or what was the significance of the ‘jingling girdles’ that the royal courtesans wore? Why is dance the entertainment of the heavens?

Why does Nala apologise to Damayanti for his (apparent) shortcomings in kissing? What is the significance of Ardh Narishwar wearing two different types of earrings? Why are the eyebrows so important or why is the mole on the cheek so erotic?

There was an entire erotic vocabulary based on the different shapes and fillings of paan—what does each one mean?

The Kamasutra holds all these answers. It is a book of great literary importance—no less than Shakespeare’s plays or Milton’s Paradise Lost as expressions of their time—and it should take its place among the world’s literatures.

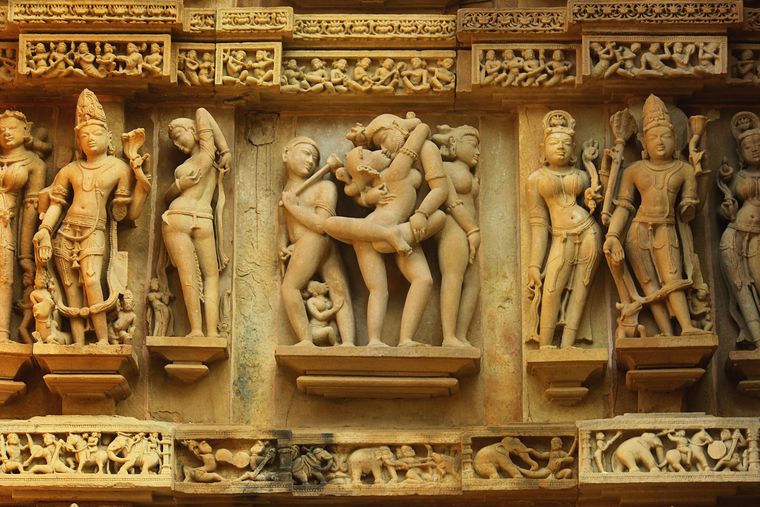

Even our old paintings and sculptures are based on metaphors from the Kamasutra. Which is why, to do any justice to a translation of the Kamasutra, one needs to have a background in mythology. The Kamasutra is not just ‘erotica’; it is not just about sex—it is the expression of sringhar rasa where each sringhar is based on a story and each story spans the three worlds and their inhabitants. If you don’t understand the stories you cannot understand the rasa.

The ancient Indians truly thought of sex as a poetic experience and had obviously spent a great deal of time devising a vocabulary for the sexual experience which was worthy of the beauty and the ‘nakhra’ that they were trying to express.

There is so much of sex and pleasure-related content online, particularly visual. And yet we have so much of writing and art on ancient Indian erotica. How do you explain this?

It is part of our evolution. As attitudes shift we are coming to the realisation that sex and sexuality do occupy a great deal of our minds. And with that has come the understanding that pleasure is important to us and not everyone’s pleasure is served by the ‘visuals’ that exist. Not everyone who enjoys sex wants to watch porn.

For many of us the experience has to be more subtle, more cerebral, more poetic. Considering the amount of literature being produced (and consumed) on the subject, there is obviously a lot of people who think like that. It is catering to a longer lasting fantasy, something that can delve just a little deeper into the long closed off recesses of the brain.

You also tell stories at corporate training programmes you conduct. Does that include erotica like Kamasutra? How do they fit in? Are the corporate participants surprised?

Normally I would use a lot of stories from the Mahabharata for corporate training sessions but in recent years there has been a call for content from the Kamasutra there as well.

The Kamasutra is quite an incredible narrative of diplomacy, on what kind of stories to tell for what occasions in order to get what kind of reaction.

It serves as a brilliant lesson on language—there is no coarse or abusive language in the book, which is pretty amazing considering that today’s vocabulary around the sexual act is synonymous with abuse.

The Kamasutra is also the first book to acknowledge women on an equal footing with men and that is a lesson worth translating into any environment.

Yes, participants are surprised, but not because I mention the text—if they have read up on me they sort of expect that. The surprise comes from what I have to say and its relevance across disciplines.

Apart from spawning other books and works of art, how does it affect life today?

I have always maintained that the Kamasutra is my not-so-secret formula for world peace. In ancient India every king, on coming to the throne, commissioned a book on sexual pleasure (generally, and surprisingly, to teach men how to satisfy a woman properly) because they believed that really good sex (sex that would lead to really good intimate, mutual pleasure) meant that the marriage would be stable. If the marriage was stable, then society would be stable and, if society was stable, then the kingdom would be stable.

In today’s society if we can use the philosophies of this amazing text to change the way we look at sex, change the abusive patterns around it, shift it from being an act of violence and aggression to a thing of beauty and pleasure, just think of the difference it would make.

As Naomi Wolf says, ‘Just imagine how differently a young girl today might feel about her developing womanhood if every routine slang description of female genitalia she heard were metaphors of preciousness and beauty, and every account of sex was centred on her pleasure—pleasure in which the general harmony depended.’

Imagine a society like that, instead of the one we have! That’s what I think is the potential of the Kamasutra.