DECEMBER 24, 1999; 4:12PM IST

Indian Airlines Flight 814, flying from Kathmandu to Delhi, was passing over Lucknow. Flight purser Anil Sharma finished serving tea to Captain Devi Sharan and copilot Rajinder Kumar and came out of the cockpit. Instantly, he ran into a stocky man in a grey suit and a red monkey cap. The man pointed a copper-coloured pistol at Sharma’s chest; his other hand held a grenade.

“Don’t move,” said the man. “I have pulled the grenade’s pin. If you do anything, we will blow up the plane.”

Before Sharma could warn the pilots, the man entered the cockpit and told them to fly to Lahore. Sharan said he did not have enough fuel to do so. The man, referred to by the other four hijackers as ‘Chief’, replied: “Then we will blow the plane up.”

VARANASI ATC, 4:57PM

It was an ordinary day at the air traffic control in Varanasi. On duty were controller Sampat Kumar and watch supervisor Y.K. Rohilla. At 4:57pm, IC 814 informed them of the hijack.

The ATC alerted Delhi. Inspector Yadav, who happened to be in the room, dialled a senior official in South Block and broke the news.

THE PLOT

The hijack had a single aim—free the most prominent terrorist in the subcontinent, Maulana Masood Azhar.

Masood had been in jail in India for more than four years. Attempts to break him out of prison had failed several times; once, he got stuck in a tunnel because of his girth. “You will not be able to keep me in custody for long,” he had told an investigator.

Masood turned out to be right. It was to free him that terrorists hijacked the plane carrying 155 passengers on the eve of the last Christmas of the last millennium.

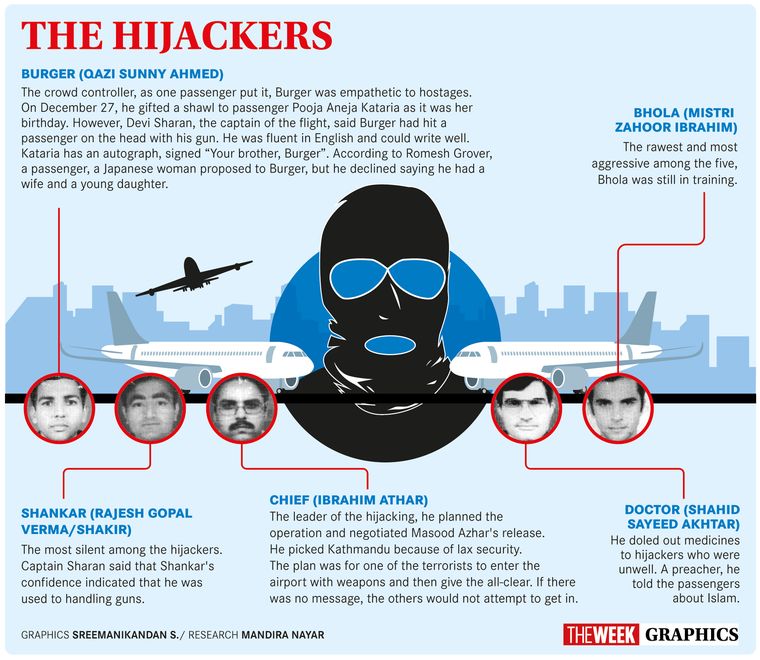

What turned out to be the subcontinent’s longest hijack drama was coordinated by Masood’s brother Rauf. The plan got its final touches on December 13, 1999, when the five hijackers—S.A. Qazi (aka ‘Burger’), A.A. Shaikh (Chief), Z.I. Mistry (Bhola), S.A. Sayeed (Doctor) and R.G. Verma (Shankar)—met at the Kathmandu Zoo. Also present at the meeting was Abdul Latif Momin of Mumbai who helped the hijackers obtain forged documents, including passports. “Momin wanted to be part of the operation,” said M. Narayanan, who headed the investigation into the hijacking. “But he was asked: If they were caught, who would carry on the operation in India? So he stayed back.”

Well-trained, well-armed and highly motivated, the five men knew exactly how to control the hostages. “They knew exactly how much pressure to apply and when to release it,” recalled R. Parthasarathy, one of the passengers.

K.V. Rajan, who was the Indian ambassador in Kathmandu, was at a podium when he got a slip of paper telling him of the news. He left for the embassy, where he had more bad news—an officer of the Research and Analysis Wing, S.B.S. Tomar, was on the flight. Tomar was a sitting duck, unless he kept very quiet.

At the embassy, Rajan got a call from a devastated Jaswant Singh. “‘You know what has happened?’” he recalls the foreign minister asking him. Singh suspected that terrorists had got off a Pakistan International Airlines flight before boarding IC 814.

INSIDE THE PLANE

Businessman Romesh Grover, who had almost missed the flight, remembers the passengers being asked to put their food trays on the floor and blindfold themselves. Grover could not tie the sash around his head, so he shut his eyes instead. The next thing, there was a cold knife at the back of his head. “I was told that I was next,” he said. “I should have really missed [the flight].”

Twenty years on, Grover has overcome his fear of flying. He was in Bangkok when he spoke to THE WEEK, and said that he had never gone back to Kathmandu. “It was a rebirth,” he said of the ordeal.

More than the fear, it was the feeling of helplessness that really shook him. “All we were given during the day was half a cup of water,” said Grover.

The hijackers wanted the flight to land at Lahore. But the ATC refused the demand. So, they threatened to kill the passengers one by one. Finally, at 6pm, the plane was allowed to fly to Amritsar.

AMRITSAR, 7PM

Captain Sharan still feels the gun’s cold barrel against his head. Twenty years on, he still has nightmares about it. “It isn’t the same each time,” he said. “The versions differ, but there is always a gun to my head.”

At Amritsar, the nervous hijackers feared a surprise operation; the crew hoped for it. Anxiety was palpable in the 45 minutes that the plane was in Amritsar.

The ATC had asked the pilot to park the aircraft at the end of runway 34, but Sharan had made it clear that he would follow the hijackers’ instructions. The ATC’s efforts to communicate with the hijackers failed. “The pilot kept asking for the bowser,” said Narayanan. “He said if it didn’t come in five minutes, they would start killing passengers.”

The bowser failed to come on time. The deadline was extended, by five minutes. To stress their point, the hijackers took seven passengers to the executive class and tied them to the seats. Two passengers, Satnam Singh and Rupin Katyal, were stabbed in the chest. Katyal was a newly-wed, and his wife, Rachna, was unaware of the attack. He bled slowly to death, becoming the lone casualty of the ordeal.

IN THE COCKPIT

Burger entered the cockpit and declared that they had killed three passengers. Another request was made to the ATC. Chief threatened to let the aircraft take off without refuelling, and the countdown from 16 began. “I had hoped that the bowser would block the way and prevent a takeoff,” said Sharan.

No such luck; he was forced to take off using half the length of the short runway. Destination: Lahore.

Katyal’s death still haunts Sharan. “My wife and I went to see his parents when we returned,” he said. His wife, Navneet, still remembers the scene in the house. On the table was the wedding album, which had just come in. “The parents were broken,” she said. “You could see that they were wondering why it was their son who had lost his life.”

Rachna remarried years later. “The day before the wedding, she came to see us,” said Sharan. “I think she hoped that I would have some answers for her, about her husband. I didn’t.”

LANDING AT LAHORE

The scariest moment Sharan had during the entire episode was when the Lahore ATC refused his request for an emergency landing and switched off all emergency lights. With the aircraft dangerously low on fuel, crash-landing was the only option.

Permission to land, however, came through just in time. The plane was refuelled; but Sharan’s request to drop off the injured passengers was denied. (He later recounted the ordeal in his book Flight Into Fear: The Captain’s Story, co-written by veteran journalist Srinjoy Chowdhury.)

The authorities allowed the plane to take off at 10:32pm, before the helicopter carrying Indian ambassador G. Parthasarathy could reach the airport. “I asked them what games they were playing,” said Parthasarathy.

MANAGING THE CRISIS

Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee was on a plane when IC 814 was hijacked. National security adviser Brajesh Mishra briefed him after he landed. At 6pm, 23 members of the crisis management group gathered at Rajiv Gandhi Bhavan in Delhi.

An officer remembers his shock at the meeting. On a blackboard were names and designations of those in the group and Salman Haider was listed as foreign secretary. Haider had retired two years earlier; the incumbent was Lalit Mansingh. “There was no handbook,” said the official, “nor a guide about how to deal with such a crisis.”

The external affairs ministry worked through the night to build international pressure. When the flight landed at Dubai, the UAE extended full support to India. After prolonged negotiations, the hijackers released 26 passengers and Katyal’s body.

ENDGAME BEGINS

IC 814 landed at Kandahar, Afghanistan, on the morning of December 26. The first Indian to arrive at the airport was A.R. Ghanshyam of external affairs ministry. He was the youngest in the Indian negotiating team.

Posted in Islamabad, Ghanshyam had flown in on a United Nations plane and was received by Wakil Ahmed Muttawakil, foreign minister in the Taliban government. The hijacking had by then become a global story. Kandahar’s tiny airport, which had barely two rooms and a functioning toilet, was packed with journalists eager to cover the talks.

But Taliban forces were eager to storm the plane. Ghanshyam met Major Usman, the core commander at Kandahar. “Even if there were 200 sheep in there, we would have blown up the plane,” said the impatient major. Ghanshyam retorted: “Your Excellency, if they were sheep, even I would.”

Other members of the negotiating team arrived by nightfall. There was N. Sandhu from the Intelligence Bureau, C.D. Sahay, Ajit Doval and Anand Arni from R&AW and Vivek Katju from the external affairs ministry. They were accompanied by relief crew and medical staff.

Ghanshyam made first contact, which led to negotiations over the phone for several days. “The army commander used to come each time there was an impasse,” said Narayanan. It was Usman who rejected the hijackers’ demand for ransom, saying it was un-Islamic. Chief was a tough negotiator; he demanded that 36 militants who were in Indian jails be freed. The negotiators tried to whittle down the number.

Inside the aircraft, toilets had stopped working. Grover recalled not eating or drinking for fear of needing to relieve himself. “We took the curtains off the aircraft windows and used them as mats,” he said. “They had tried to clean the bathrooms without the right equipment and the carpets were soaked.”

Each morning, the hijackers would threaten to kill more passengers. “They were very rude to the passengers on December 28,” said Narayanan. “They didn’t allow food or water to come in. The situation was getting bad.”

On December 30, the hijackers told the passengers that they were going to die. “Everyone was asked to bow down,” said Parthasarathy, the passenger. “We sat there for a long while.”

But talks resumed after Afghanistan’s foreign minister intervened. “As time stretched on, I realised that there was some hope,” said Parthasarathy. “[The hijackers] had used the plane’s system [to address the passengers], which meant they wanted the negotiators to hear their threat.”

It worked. The negotiators struck a deal with the hijackers and the following day, Jaswant Singh flew to Kandahar with three terrorists whose freedom the hijackers had demanded—Masood Azhar, Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh and Mushtaq Ahmed Zargar.

Singh was later criticised for his decision to accompany the terrorists. “The threat was real; it could not be brushed off: what if the aeroplane is blown up?” he later wrote in his memoirs.

Singh said it was the most “emotionally draining decision of his life” and that he could not accept the responsibility of letting the hostages die. “At first I stood against any compromise; then, slowly, as the days passed, I began to change.”

The passengers were freed after the three militants landed in Kandahar. They were flown back to India on a special flight, even as Taliban ensured safe passage for the terrorists.

“I remember that we had vowed to visit every pilgrim spot if we survived,” said Pooja Aneja Kataria, a passenger. “Twenty years later, we still have Pashupatinath left.”

Survival instincts

JEAN MOORE was the only American on board IC 814. She helped the hijackers spell ‘coffin’ when they sent their demands in writing. It was only on the fourth day, when the hijackers asked for passports, that they discovered she was American. She came back home with three pieces of bread, which she had hidden away to eat when desperate.

Massive evidence

THE ILL-FATED aircraft became possibly the largest piece of evidence in any investigation. The sleuths got fingerprints of the hijackers from it. It was later sold as scrap—the hull is believed to have fetched 022 lakh. A model, complete with seat numbers, was created to be produced in court and a court official was trained to assemble it, as it was unwieldy.

Language barrier

THE INDIAN negotiators in Kandahar suspected that they were being monitored. Three of them who knew Kannada—Anand Arni, A.R. Ghanshyam and C.D. Sahay—often spoke in the south Indian language. Pakistani newspapers reported that the Indian negotiators spoke in code language. Thus proving the suspicion that their rooms were bugged.