JAWAHARLAL NEHRU was expansive in everything that he wrote and spoke. After having served as a leader of the freedom movement for 30 years, he was prime minister for 17. It took 48 years to collate the archival material generated over the 47 years of his public life. The Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, popularly known as the Nehru Project, is now complete, with the recent release of the 100th and final volume of the collection.

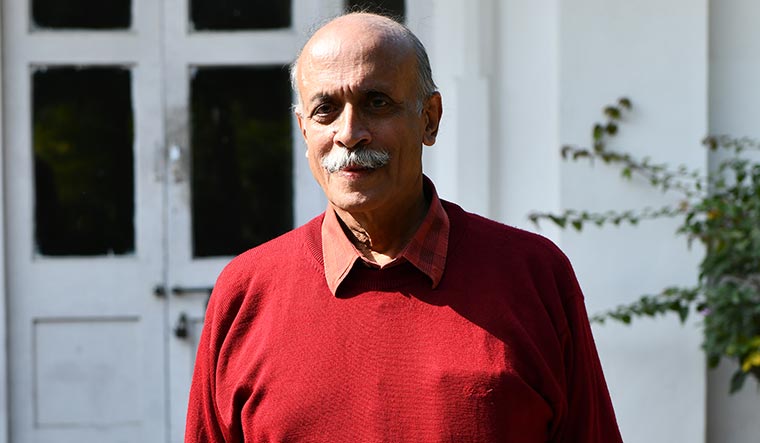

Madhavan K. Palat, who took over as the editor of the collection in 2011 and at volume number 44, describes it as the largest single archival publication of a historical kind which offers a panoramic view of 20th century Indian history from the perspective of one of its key figures.

“We do have publications of correspondence of Sardar [Vallabhbhai] Patel, Rajendra Prasad, Rajaji [C. Rajagopalachari] and so on. But none of them can be compared with the prime minister himself. And, especially a prime minister who was in a leadership position of a kind that was just next to [Mahatma] Gandhi’s,” said Palat.

The Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund started the project in 1972. Prime minister Indira Gandhi, who chaired the fund, saw in it a lasting memorial to her father. The first editor was historian Sarvepalli Gopal, who laid the foundation by assembling all the documentation. This included the archives at Nehru’s house as well as documents from various government departments. Editors who followed in his shoes include historians like Mushirul Hasan and Mridula Mukherjee.

The volumes contain Nehru’s speeches, interviews, letters and minutes of his meetings with world leaders among other documentation, which could help the reader understand how various decisions and policies were arrived at.

Palat, however, said that there are blank spaces in the project because of the ministries of external affairs, defence and home not sharing documents with the research team. Specifically, he spoke about the inability to publish papers related to Kashmir, China and Pakistan, and a majority of the defence matters.

Palat said that Nehru’s correspondence with president John F. Kennedy after the Chinese invasion in 1962 was procured from US sources. “I would obviously like to have our own government’s official, authenticated version, not the American copy of Nehru’s letter, although that is totally authentic,” he said.

Even the record of Nehru’s discussions with Kennedy when he was in America in 1962 could not be procured from the government. Palat, however, discovered it by accident. Three weeks after the Kennedy-Nehru meeting, the foreign secretary sent the minutes of the discussion to Indian ambassadors. By chance, a copy arrived in a collection, and Palat used that.

Getting specific documents on whether Nehru asked the Israelis for help in 1962, and if he did get any help from them, would have helped since it is all shrouded in mystery. “There are various statements by various people,” said Palat. “Actual documents would have helped. It is not surprising anymore since we have a close relationship with Israel now. Earlier, in the context of non-alignment, taking help from Israel would have been debatable.” Palat thinks the government officials are afraid of getting penalised if a document generates controversy. “Their way of exercising caution is to put a blanket ban on sharing all documents,” he said.

The initial part of the series covers the planning for a post-independent state that began even before independence. Nehru chaired a number of sub-committees; Subhas Chandra Bose was the president of the Congress then. Then, there was the question of partition and communal riots.

The volumes also reveal Nehru’s nervousness about the reorganisation of the Indian states. “He had just come out of partition,” said Palat. “To his mind, states’ reorganisation looked like more partitions coming. However, it worked very well. On Punjab, he took a stand, saying what the [Shiromani] Akali Dal wants is a communal state, and not a linguistic one. After his death, it was conceded as a linguistic state.”

While Nehru was known to be an impatient man, in his letters he would not tire of explaining matters, and came across as a flexible and accommodating leader. “Master Tara Singh, for example, in his letters to Nehru, would go on and on about Punjabi Suba and his demands for it,” said Palat. “Nehru would keep on explaining to him the contrary view. You can tell that Nehru means to write, ‘See I am weary of telling you the same thing again and again, but let me say it again’.”

Also, the exchanges were always courteous and civilised, no matter the differences. According to Palat, the only two persons who seem to have offended Nehru in their letters are the socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia and an Army general, Nathu Singh Rathore.

Nehru, said Palat, responded to every letter. He would normally reply the next day, and would apologise even if it were late by a few days. “Everything that came out of Nehru’s hands was actually drafted by him,” he said.

On the question of the project’s relevance in today’s times, when there is a perceived assault on Nehru’s legacy, Palat said he was under attack from the extreme right and the extreme left even during his own time. “He has to be relevant for the important role that he has played in our history,” said Palat.