KUNDAN BHOI, 22, had been meeting his elder brother in Udaipur Central Jail in Rajasthan once in two weeks. He trudged 15km from home every time. But the last time he went there two months ago, the prison had stopped allowing visitors because of the pandemic. He returned home distraught. Later, the prison advised him to apply for an online meeting through the National Prison Portal.

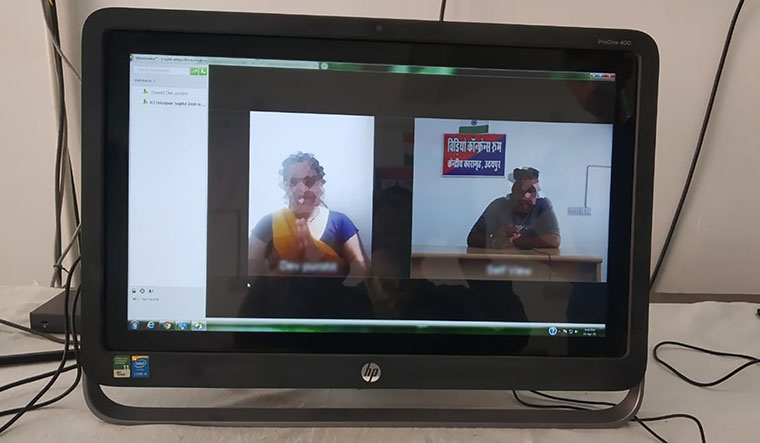

Such meetings, called eMulakat, had started in Rajasthan on April 2. On the ePrisons page, Bhoi keyed in the details of his elder brother, who was serving a seven-year sentence for murder. An OTP confirmed his registration for eMulakat and he got a website link for a video-call and the date and time.

When he logged in from his smartphone for that first video-call with his brother, he was delighted by the swiftness of it all. “My brother met all the family members all at once. We showed him his house waiting for his return. This system is so time-saving,” says Bhoi, who is doing his BCom in a Udaipur college. “Better than going all the way to the prison complex, waiting there and then going through multiple people to meet my brother.” He has met his brother online four times now. “I hope they keep this system working even after Covid-19.”

Surendra Singh Shekhawat, deputy inspector general of Rajasthan prisons, is also excited about how the state is embracing the new system. “We are No 1 in running eMulakat,” he says. “It is happening in most of Rajasthan jails. And not just central jails. There are five subjails in Udaipur; even they have it.”

Shekhawat concedes that connectivity is a major worry and that many prisoner families in remote, tribal belts do not have access to the internet. “Prisoners get five minutes to meet their kin via video-calls. Yes, they complain about the short time. There are some technical problems,” says Shekhawat, who plans to upgrade the infrastructure for eMulakat. “We are also in the process of getting families to make online payment for canteen material, so they do not have to come every time to deliver fruits and knick-knacks.”

Restrictions on visits and fears about the virus had led to riots in the Dum Dum correctional facility, the largest prison in West Bengal, in the third week of March. Four inmates were killed and 60 policemen injured in the clashes and arson. “A complete ban on visitations can do great emotional and mental damage to prisoners in these uncertain times,” says Sanjeev P. Sahni, criminologist and principal director of the Jindal Institute of Behavioural Sciences, Jindal Global University, Sonipat.

Sahni says, “States like Odisha, Rajasthan, Punjab and Gujarat are leading in digitisation of visits. Odisha has even ordered [starting of] eMulakat in all 30 district jails. Prisons are establishing visitor rooms equipped with laptops and broadband, and making suitable arrangements at prison cells. These facilities are advantageous for visitors from poorer families.”

But eMulakat scheme remains under-utilised for various reasons. R. Rochin Chandra, director of the Centre for Criminology & Public Policy, says prisons tend to balk at spending on high-speed wired internet connection for eMulakat as it is expensive. “The states are struggling to cover the usage fee for video-calls.” In prisons where eMulakat is working well, he says, the demand is increasing, which is why inmates get to see their relatives only for five minutes. And if they somehow miss an appointment, the web link expires, and they have to wait for long for a new booking. Chandra also notes that many families have lost their livelihoods during the lockdown and may not have the means to take internet subscriptions.

Criminal psychologist Anuja Trehan Kapur warns against making eMulakat a norm. “These are video recordings at the end of the day. They can be weaponised later as evidence for punishment even though it is illegal,” she says.

Much has been said about mass release of undertrials and petty offenders to decongest prisons, but it is easier said than done because lawyers are no longer readily accessible. “The district legal services authorities are themselves wary of prison complexes which are seen as high-risk contamination zones,” says Smita Chakraburtty, founder of Jaipur-based Prison Aid Action Research, who has been working across jails in Rajasthan as an independent observer and adviser. She says prisoners should be allowed to use eMulakat to interact with their lawyers as well. One can get out of prison only through remission or bail, and one needs a lawyer’s help for that, she notes.

Chakraburtty says open jails are better equipped to handle overcrowding. Rajasthan has the largest number of open jails in the world, nearly 40 of them. “Nobody has run away from open jails,” she says. “Prisoners live with their families. Closed colonial-era structures do not work anymore; they are inhuman and expensive. Even the Supreme Court has admitted that open prisons should become the norm in the future. There is no need for eMulakat there.”