In my younger days, I have gone bungee jumping, scuba-diving, jet-skiing and indulged in a few other adventure activities which, with age and wisdom, I might not repeat. Caving was something I had never tried. The only time I had gone underground was at the Catacombs of Domitilla in Rome—a network of burial sites of early Christians dug into volcanic rock. The walls are covered with elaborate paintings of Christian symbols and scenes from the gospels. But exploring the caves of Meghalaya, of which there are more than 1,700, was a radically different experience.

The two kinds of underground spaces that I visited in Rome and Meghalaya could be called a theatre in which the battle between religion and science was being played out. While one documented the origin of Christianity, the other advanced scientific discovery—like a stalagmite from Krem Mawmluh, a seven-kilometre-long limestone cave in Sohra, that helped prove the existence of a 200-year-long drought which took place around 4,200 years ago, after the Ice Age. The term Meghalayan Age was coined to describe this period. The drought destroyed many civilisations around the world, including the ones in Mesopotamia and in the Indus Valley.

Caving expert Bryan Daly Kharpran—who founded the Meghalaya Adventurers’ Association (MAA) in 1990, and was part of the team that discovered the stalagmite in Krem Mawmluh—says that the eco-system of the caves provides a clue about the evolution of life forms on earth. “Since cave fauna have lived in total darkness, they have, over generations, adapted and evolved,” he says. “They have no eyes, since they have become redundant. They are white because of lack of pigmentation. They feel about using extra-sensory hairs that are ultra-sensitive. So a cave cricket might be five centimetres long, but its antenna will be ten times its body length.”

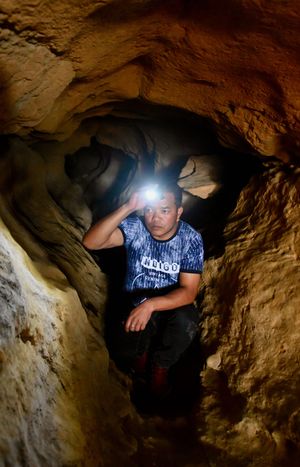

We visited Krem Mawmluh on a beautiful, glossy morning, which is a rarity at one of the wettest places on earth. Sunlight pooled on a pebbled stream, which we crossed to reach the entrance of the cave. A rough-hewn wooden ladder sank into a black void. My colleague, our guide Rishan Wahlang, and I climbed down into a cavern. A little way in, the light converged into total darkness, and there was only a slim shaft of it from our headlamps slicing the darkness.

I felt my way from one slippery rock to the next, praying that I would not fall. Then, a moment before hearing Rishan’s warning, I stepped into freezing water and yelped out. The water reached up to our thighs and we splashed our way across it as fast as we could. After shaking it out of our gumboots, we encountered the next obstacle—the roof of the cave slanted in, so that we could not move without bending low. It gave the phrase ‘back-breaking’ a whole new meaning. Rishan disappeared out of sight, and I heard my colleague calling out to him, his voice eerily hollow. Desperate to catch up, I crawled ahead, my helmet clunking against the roof. All that creeping, ducking, balancing, wading and climbing could perhaps be called a low-grade version of a Navy SEAL training session.

“Are there snakes here?” I asked Rishan.

“Oh yes,” he answered. “Some of these caves are breeding grounds for snakes.”

I stopped dead in my tracks. Snakes ranked pretty high on my list of things to avoid in life, right up there with syringes, screeching children on airplanes and books by Greek philosophers. One kilometre into the cave, we were spent and had to turn back. Upon surfacing into the light, I had a newfound appreciation for the sun, level ground and life without gumboots.

“You didn’t go far enough to see the formations?” Bryan asked when we met him the next day in Shillong. Apparently, we had missed some beautiful stalagmite formations in the cave. (I thought it was a fair exchange for the pleasure of missing snakes.) Bryan lived in a charming house full of framed photographs, with a front yard where several children were playing. Only six or seven caves had been discovered in Meghalaya when he founded the MAA. Now, almost 30 years later, his team has identified over 1,700 caves, of which around 1,000 have been mapped.

“More than any other adventure [activity],” he told us, “Ninety per cent of caving is scientific work. If you climb a mountain, whether you succeed or not, it is finished. The pleasure of discovering a cave is different. You are exploring something that is unknown, going completely into the dark, and not knowing what obstacles you are going to encounter or how big the cave is. That is the beauty of caving.”

Bryan and his team have just finished mapping the longest sandstone cave in the world—Krem Puri—over 25 kilometres long. We were possibly one of the first travellers to visit the cave after it was mapped in February. Getting there itself was an adventure. A trail cut through a dense forest. The loose sand and slippery rocks made it a treacherous trek. On one side, the mountain sloped into a gorge, and I tried not to look down. Around 45 minutes later, we reached the entrance of the cave, a shadowy portal into the unknown. We did not have a guide with us, so we only went a little way into the menacing darkness.

Krem Puri translates to ‘cave fairy’ in Khasi, a fitting name because of all the treasures it holds, from the fossils of shark teeth to, possibly, those of marine dinosaurs. According to Bryan, it is one of the most complex cave systems in the world. Every day people get lost there. “It is a complete maze,” he says. “Even I would think twice before entering unknown passages.”

The first time Bryan saw a cave was in 1964, when he went for a picnic with his family. Inspired by the adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer, he wanted to explore it but the others forbid him. So he got some local boys to accompany him inside. Today, the cave has become a show cave called Mawsmai, with ticketed entry and artificially-lit corridors.

It was the last cave that we visited in Meghalaya. Inside, a woman in a salwar kameez knuckled past us, ignoring the entreaties of her husband—a portly man struggling to keep up with her. A group of boisterous youth with pushed-back sunglasses and slick hair ambled ahead of us, seemingly more interested in their selfie sticks than in the cave.

After our ‘SEAL training session’ in Mawmluh, Mawsmai felt bland—like eating spinach after steak. It is not like I will ever be an experienced caver like Bryan. I will never get excited at the prospect of freezing water and claustrophobia. But I will no longer be puzzled about why people explore caves. There is something about the sufficiency of nature that calls out to the insufficiency in us. We are built to seek the unsought after. Sometimes, our minds are brightest when the light is dimmest, and each step we take is a step into the unfathomable.