Sukumara Kurup has been on the run for 37 years, after faking his death by murdering a man who resembled him. His alleged intention was to commit insurance fraud. Over time, the murder and the vanishing act combined has made him an enigma. Even after all these years, this gulfukaaran (man employed in the Middle East), and his crime continue to haunt popular imagination—stories are still being written about him, and top actors have played him on screen.

THE AMBASSADOR OUTSIDE HARI TALKIES

Around midnight on January 21, 1984. K.J. Chacko, 30, was sipping black tea outside Hari Talkies in Alappuzha when the killers' spotted him. A film representative, Chacko was at the talkies to deliver movie reels. Considering what happened later that night, the movie’s name would prove to be coincidental—Keni (The Trap).

“I was with Chacko till midnight. We both had tea after the second show,” recalls K. Sreekumar, son of the then owner of Hari Talkies. “I had asked him to stay back and leave in the morning. But he had promised to take his pregnant wife to the church feast [the next morning]. After the tea, I bid him goodbye and went inside the theatre. I never saw him again.”

After Sreekumar left, Chacko stood there alone, waiting for any bus that would take him home. Soon, a black Ambassador pulled over and offered him a lift. KLQ 7831 had driven past him twice that night, but he had not noticed it. In the car were three men—Sukumara Kurup’s loyal driver Ponnappan, his wife’s sister’s husband Bhaskara Pillai, and Shahu, an attender in Kurup’s company in Abu Dhabi. The trio had agreed to assist Kurup allegedly for a cut of the insurance money. Chacko gratefully accepted the lift and sat in the back, flanked by Pillai and Shahu. Kurup tailed them in another car, KLY 5959.

Kurup was inspired by an insurance fraud committed in Germany; the perpetrator faked his death and his nominee collected the money. Just before Kurup left Abu Dhabi for Kerala, he had taken an insurance policy worth 3,01,616 dirhams (roughly Rs30 lakh)—a sizable amount in the 1980s. His wife, a nurse, and two kids were still in the emirate.

Kurup had initially planned to rob a lookalike’s body from a mortuary. When that plan fell through, the four planned to rob graves. Murder was Plan C. They had been scouting for a lookalike for days when they saw Chacko outside Hari Talkies.

AN ACT IN HASTE

In the car, Pillai and Shahu force-fed Chacko with poison-laced liquor and choked him to death. Then they drove to Pillai's house, Smitha Bhavan in Cheriyanadu. There they stripped the body of its clothes, wedding ring and watch, dressed him in Kurup’s outfit, and charred his face. They then loaded the body into the boot of KLY 5959.

The two cars then headed to nearby Kollakadavu, a scenic village on the banks of the Achenkovil river. The site chosen for the ‘accident’ was a paddy field bordering the river; the field is now known as Chacko paadam (Chacko field). At the site, the body was transferred to the driver’s seat of KLQ 7831 and doused with 10 litres of petrol. The car was then pushed down into the field and set afire.

While dousing the car with petrol, the gang had spilt some; the raging fire jumped from the car to the spilt fuel, burning Pillai’s arms. The four jumped into an adjacent field to douse the flames, and then fled. In the confusion, they left behind their gloves and a rubber sandal.

Early on January 22, 1984, the Mavelikkara police received a call reporting the burning car. Circle inspector M. Haridas and his team reached the scene around 5am. They had no inkling that they were stepping into a crime scene that would haunt them for the rest of their lives. “The car was completely burnt and there was a charred body behind the wheel. Local residents in the crowd told us that the car belonged to an NRI named Sukumara Kurup,” says Haridas. His team found the gloves, a matchbox, and also a petrol can from the location. The gloves had burn marks, and a few hairs stuck to it. They also found footprints fleeing the scene. A case file—22/84—was opened in the Mavelikkara police station.

“I smelled something fishy right from the beginning,” says Haridas. “The policemen who were sent to inform [Kurup’s] family about the death came back and told me about the passive reaction from relatives.” Intrigued, he again sent two policemen to Pillai’s house. Kurup used to stay at Pillai’s house every time he returned from the Gulf—partly due to the matrilineal system and partly due to his family's disapproval of his marriage with a girl from a poor background. They found Pillai’s wife cooking chicken curry—something unthinkable in a traditional Hindu household in Kerala, immediately after the death of a relative.

What he did next proved to be the turning point in the case. While requesting a post-mortem, Haridas wrote against the name of the deceased: “A man said to be Sukumara Kurup”. This piqued the curiosity of police surgeon Dr B. Umadathan, who did the post-mortem.

His inquest confirmed that the dead man was murdered and set on fire, because there were no traces of charcoal or ash in his respiratory tract. The presence of liquor and ethyl alcohol in the digestive tract added to the mystery. Also, no ring or watch was recovered from the body during the post-mortem—unusual for a wealthy NRI like Kurup.

FULL SLEEVES; PARTIAL DISCLOSURE

Haridas then called Pillai to Mavelikkara police station for an inquiry. Pillai told Haridas that Kurup had many enemies in the Gulf, and that one of them might have killed him. During his visit to the police station, Pillai was dressed in a full-sleeved shirt—unusual in Kerala in the 1980s. Curious, Haridas asked Pillai to roll up his sleeves, which he did reluctantly. There were burns—not older than 24 hours old—on his elbow. On further examination, the police found burn marks on his right leg; his eyebrows, too, had been singed.

Cornered, Pillai confessed that he had killed Kurup for not keeping the promise of finding him a job in the Gulf. Haridas did not buy the story. He went straight to Pillai's home to gather more information. That was when he found that Kurup had two cars; KLY 5959 was brand new. Haridas wondered why Kurup had driven the old car on the night of the fire. Haridas spotted some burnt hairs on the porch. The fact that Kurup's driver, Ponnappan, was missing added to the mystery.

A CALL, AND MORE CLUES

On January 23, 1984, Haridas got a call from Kurup’s distant relative. The caller informed the officer that the corpse was not of Sukumara Kurup, and that he had got this information from driver Ponnappan. Ponnappan told him that while driving Kurup, he had hit a stranger accidentally, and that they burned his body. Ponnappan allegedly added that he had dropped Kurup in Aluva (more than 70km from Alappuzha).

“I believed the first part of the story. But the second part did not add up,” says Haridas. The investigating officers returned their focus to the man in hand—Pillai. On further grilling, Pillai revealed that Kurup was running out of money to fund a palatial house he was building in Alappuzha town. He first shared his plan with the other three over drinks, Pillai said. He added that Ponnappan, who was initially reluctant, was forced to join them. The four had met at Kalpakavadi Restaurant, Alappuzha, on January 21, 1984, to fine-tune their plans. Pillai also described in detail how they found the victim and how he was murdered. But he had no idea who the victim was.

THE MANHUNT BEGINS

Police teams were dispatched to find Shahu, Ponnappan and Kurup. Haridas’s team went to Trivandrum International Airport and sifted through thousands of embarkation cards for Shahu’s details. They found that Kurup had filled in Shahu’s card as the latter was illiterate.

Mavelikkara circle inspector K.J. Devasia nabbed Shahu from Chavakkad, a coastal area in Thrissur district; he was packing his bags to leave for the Gulf via Kochi. Ponnappan, too, was arrested soon.

However, the investigators did not have the same luck with Kurup. “He had a narrow escape,” says Jayaprakash, then circle inspector of Kayamkulam. “The owner of the [Alankar] lodge, [in Aluva], identified Kurup when we showed him the photograph and said that he had just left.” Kurup had got a 72-hour head start—an advantage that has helped him cock a snook at the cops for 37 years.

IDENTIFYING THE VICTIM

On January 27, 1984, Haridas had a chance meeting with Sreekumar, who had come to lodge a missing person complaint for Chacko. “When Chacko did not return to the theatre for the next few days, I got worried and went to his house,” says Sreekumar. “Chacko's family had not felt anything unusual, as Chacko used to travel extensively as part of his job and used to stay away for days. But I knew that Chacko was heading home that night [he got murdered], and asked them to register a complaint with the police.” The body found in the field had been buried by then.

On February 1, the body was exhumed for a second post-mortem. Using a technique called superimposition (one among the first cases in the country to use this), it was confirmed that the body belonged to Chacko. That day, the ‘Sukumara Kurup murder case’ was officially renamed the ‘Chacko murder case’.

The charge-sheet named Pillai and Ponnappan as the first and second accused on charges of murder, criminal conspiracy, and destruction of evidence. Shahu, initially charged as one of the accused, turned police approver. Pillai and Ponnappan were found guilty by the sessions court and sentenced to life. The police believed that the wives of Kurup and Pillai were in on the plan, so they were named third and fourth accused. Since the police were still chasing Kurup, he was not named in the charge-sheet!

A MAN OF MANY FACES

Kurup was a quintessential gulfukaaran of the 1980s. He loved to splurge, creating goodwill among relatives and neighbours. He hailed from an illustrious family in Alappuzha, with strong political connections on both maternal and paternal sides (something which allegedly gave him an advantage in the initial days of investigation).

Kurup had a dubious past not known to many—he had feigned his death once before. He had a short stint with the Indian Army Medical Corps after his pre-degree course (equivalent to Class 12). But he deserted and bribed the official who was assigned to track him down to write a report that Gopalakrishna Pillai (his official name then) had died. Later, he took a passport in the name Sukumara Kurup and left for the Gulf. “To fake one's own death is not an easy task,” says Alexander Jacob, retired director general of police (prisons), Kerala Police. “That he managed to keep this incident a secret shows his shrewdness.”

REVOLUTIONARY ROMANCE

Kurup fell in love with Sarasamma during his Army days in Pune. Sarasamma was a trainee nurse there. The couple got married in a temple in Matunga in Mumbai, without the knowledge or permission of Kurup’s family. Soon after the marriage, he left the Army and went to the Gulf. He took Sarasamma, too, with him, and she found a job as a nurse. Sarasamma's family came out of poverty after her marriage to Kurup—a fact that had made Pillai loyal to him.

FLIGHT FROM JUSTICE

From Aluva, Kurup first went to Chennai, and then to Bhutan, and later to the Andamans. From there, he came to Bhopal. Police did reach all these spots, only to find that he had given them the slip.

“Four (undercover) policemen stayed in the neighbourhood of Kurup’s house for eight years,” says George Joseph, retired superintendent of police, who was part of the special investigation team (SIT) investigating the case. “But nothing yielded results.”

According to Joseph, police used to get thousands of telegrams every day from different parts of the country, reporting sightings of Kurup. “The case caught the fancy of every common man so much so that they started using Kurup's name even to settle scores with neighbours,” he says.

Kurup had visited his house sometime in February 1984, a month after the murder. But he outwitted the police once again. That had created a huge uproar across the state, and forced the government to appoint an SIT.

HELP FROM THE TOP?

Retired superintendent of police Harris Xavier, who was part of the SIT, believes that Kurup would not have escaped, but for some political help. “He had connections with higher-ups, and it did help him escape,” he says. Following tip-offs, the police looked for him all over the country. But all they got in so many years were just testimonies of his sightings. In 1990, Kurup was declared as an “absconder”.

The Chacko murder case is one in which the maximum travel allowance has been sanctioned by the Kerala government, thanks to the investigation that extended to all the states in the country and abroad, including Las Vegas. As many as one hundred people have been arrested at different times as suspects. Even the Interpol has arrested a few as suspects. But all were freed.

WILD THEORIES

Conspiracy theories about Kurup's life abound. The most popular one was that he had become a monk in Nepal. Another story was that he had fled for the Gulf from Nepal. When Kurup's younger son, Sunit Pillai, got married in 2010 at the Sree Vallabha Temple, in Thiruvalla in Pathanamthitta district, he was described as the son of “Mr Sukumara Pillai” with no prefix of “late”. Another story is that Kurup converted to Islam and is living in a mosque in Saudi Arabia.

But Joseph insists that Kurup, who had severe cardiac issues, must be dead by now. “Kurup was spotted at the district hospital, Dhanbad, Bihar, in 1989,” he says. “He was admitted with severe cardiac issues. The name given was P.S. Joshi, and he was 50. A Malayali nurse, who had her suspicions, asked him about his original home; he vanished the very next day with his medical records. The same person has been sighted in nine states including Odisha, West Bengal and Assam. He was last spotted in Narayanpur [currently in Chhattisgarh] in January 1990. He vanished from there, too. Doctors told us that he would not survive for more than a week as his condition was that critical.”

MOVIE MYSTIQUE

There have been many murders across the country that have been equated with Kurup’s crime. In November 2020, a Tamil Nadu lawyer named E.T. Rajavel and his wife Mohana got double life-term for murdering a lady named M. Ammasai in December 2011. The murder was plotted to fake the death of Mohana, who was facing cheating charges in Odisha.

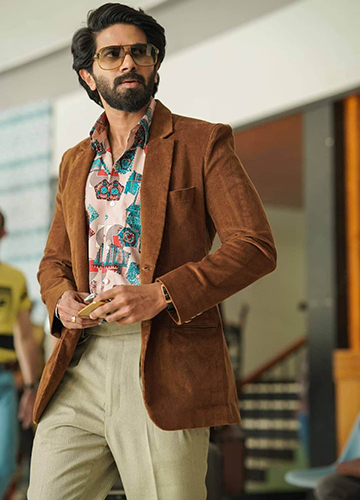

The first film inspired by the Kurup case, NH 47, was released within a few months of Chacko’s murder. Master filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s film Pinneyum (2016) has a storyline similar to the incident; Adoor has denied any connection. The latest in the list is Kurup, a multi-lingual film starring Dulquer Salmaan, which is expected to have a theatrical release in May.

THE PEOPLE, TODAY

Chacko's wife, Santhamma, who was six months pregnant at the time of her husband’s death, has pardoned Chacko’s killers. “We do not know whether he is alive or dead. However, we forgive Kurup and the others involved,” she says.

Pillai refused to meet THE WEEK. He is still living in Puliyoor in Alappuzha district, with his son and family.

Ponnappan committed suicide soon after serving his jail term. Shahu went back to the Gulf and is still working there. Sarasamma and Pillai's wife—both sisters— were acquitted for lack of evidence. Sarasamma lost her job as a nurse in Abu Dhabi, and was ostracised by the community. She lives a secluded life in Puliyoor.

Properties of the Kurup family had been attached by the government after he was declared a fugitive. “We lived in a pathetic condition,” says Sunit, Kurup’s youngest son. Does he have any memory of his father? “I was very young when it happened. I do not remember anything,” he says.

Chacko's son, Jithin, who has never seen his father, is still livid about the whole case. “My mother may have forgiven Kurup, but I will not,” he says. When asked whether he is hopeful that Kurup would be caught, Jithin says the history of the case does not make him optimistic. He adds: “My father could not hold me even once. My mother has not recovered from the jolt yet. The greed of a single man has destroyed many families. I want him arrested.”

Amid all these shattered beings, Kurup's bungalow, for which he killed Chacko and destroyed many more lives, stands lonely and abandoned—like a guilty witness.