Inside the long, narrow and serpentine lanes of a slum in New Delhi, 13-year-old Raveena Jankipura contemplates suicide. She feels “trapped, suffocated and abused” in her two-room house. Three months ago, her father lost his job in the lockdown that followed the second wave and has been home ever since. He has been sexually and physically abusing her; he recently burnt all her textbooks. Her mother is battling Covid-19 in a government hospital. With schools shut, Raveena is working as a daily wage labourer in a nearby factory. She looks forward to the backbreaking shift at the factory because it gives her an excuse to stay away from her perpetrator—her own father.

On April 20, in Jhalamand village of Rajasthan's Jodhpur, Akhil Mandopa, 12, was forcefully married off to a girl three years younger to him. To escape the prying eyes of the administration and activists, the 20-minute ceremony was conducted at 2am in fields far away from home. A marriage certificate was ready by morning, much to the chagrin of authorities. Around the same time in Jodhpur, Radha, 14, who had been married off as a toddler a decade ago, was forced by her in-laws to move to their house during lockdown. When she refused and questioned the legality of the marriage itself, they assaulted her and her family. She was later hospitalised.

In Maharashtra, children from the tribal areas of Jawhar and Mokhada have been waiting for more than six months to get their supplies of medicines, protein powders and essential vitamins, which otherwise was delivered regularly here. A majority of the children here have been reported to be malnourished with acute vitamin deficiency, and regular government programmes help keep their health and vitals in check. However, the second wave made it almost impossible for doctors and activists to visit the area. “The children have lost weight. We have no records or vitals taken,” says Ramchandar Bhoye, who works with the Samta Foundation in Jawhar. “We are waiting for the pandemic-related stress to ease out and then we will restart.”

In a posh Delhi locality a few kilometres from the India Gate, a 16-year-old girl was shocked to see her name tagged in thousands of posts on her Instagram feed at around 11pm. A bunch of her classmates from a highly reputed school were cyber-bullying her. The family learnt that a boy from her class had initiated it, seeking revenge as the girl had stopped talking to him for a few days. “She received rape messages and death threats on Instagram that night from random people as an intimidation tactic. We were shocked,” said the girl’s mother. “I had to call the boy at midnight to put an end to it and then filed a complaint with the police.”

As Covid-19 continues to ravage through the country, children have emerged as its biggest victims and silent casualties—ignored, neglected and abused. As families lose their sources of income and basic survival takes a hit, the vulnerabilities of children have become more pronounced. And, the impact is multidimensional. The past year and a half of the pandemic has seen a sharp rise in the violation of rights of children who are already at a disadvantage, be it in institutions or at home. And, these rights range from the right to health, education and family life; right to be protected from violence and from economic and sexual exploitation to right to an opinion; right to be protected from any hazardous employment; right to nutrition and the right to a happy and secure childhood. “The severity associated with the violation of children's rights is the most massive problem we are facing on ground right now,” said Sonal Kapoor, founder director, Protsahan India Foundation, which has been working to address child rights violations in India. “In the last four months alone, we have seen 650 case files of families in which the rights of more than 1,700 children have been completely taken away in a single city. This is child protection emergency.”

Lockdown measures also exposed children to a range of risks as confinement resulted in heightened tensions at home, including domestic violence. And while the risk of violence against children increased, child protection services found themselves tied down because of the lockdown restrictions. With loss of employment and rising poverty at home and schools remaining shut, children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds have been forced into manual labour, begging, early child marriage and paid domestic chores; they probably would never go back to school again. Children from middle and upper middle class families, on the other hand, are experiencing increasing levels of anxiety and depression as they remain cooped up indoors. With no access to public parks and gardens, no avenues for sports and recreation, and with schools remaining shut, these children have begun to show signs of restlessness and frustration.

“Not that these issues weren't there before, but in the past year and a half they have enormously intensified,” said Kapoor. She spoke about documented cases of transactional sex where parents send their girls, aged 11 to 15, to unorganised brothels in exchange for food. They return after two to three hours, “in a completely distraught state, as good as a dead body”, but they bring along 2kg of wheat flour and 4kg of rice to last the family for a week.

Around 10 days ago, four children, 12- to 13-year-olds, went missing on a single night in Bhubaneswar. Officials suspect it to be a racket and are still investigating it. “These are pandemic's forgotten children,” said Dr Benudhar Senapati, director of Childline in Bhubaneswar, who has been addressing the issues of street children for more than a decade now.

“They have no food, no first aid. They do not get themselves tested even if they have Covid-19. And if they test positive, nobody cares.”

A few months ago, his team of volunteers, who visit the children in three battery-operated rickshaws to educate them on Covid-19, found a boy who had “mistakenly” travelled to the city from Maharashtra. When the team found him, he had fever and looked lost. Later, he tested positive for Covid-19 and was quarantined. Before the pandemic, said Senapati, these children had access to mentors, friends and activists who would help them and provide for them. But with a strict lockdown in place, they have become lonely and fearful as they see people dying in front of them.

“At such times, it is the psychosocial problem that comes into sharp focus,” said Senapati. “They live in fear and anxiety. When they are sick, there is nobody to take them to the hospital. Nobody even has any data on how many street children died, how many got sick and how many continue to struggle on the streets every day. In the pandemic, the number of calls we would receive directly from children has also reduced, because they have no access to a phone. Now it is the police that gets such children to Childline for help.”

The pandemic has upended the lives of school-going children, too. According to a social activist in Maharashtra, an unprecedented number of school-going girls and boys have begun assisting their parents in the unorganised labour sector, either at construction sites or as domestic helps or in factories rolling agarbattis and kohl sticks for 8-10 hours. “The parents find them to be an additional mouth to feed, given that the school's mid-day meal programmes are shut, and hence make them work to earn,” the activist said. “They are being paid Rs3 to Rs10 a day, but nobody is talking about these things.”

The pandemic also made it convenient and easier for child marriages to take place, said Dr Kriti Bharti of Saarthi Trust, which works in the area of child marriage annulment in Rajasthan. Children are being married off as earnings have depleted in families and so “it is considered ideal to have one less mouth to feed”. Also, since the government limited the number of wedding guests, families did not have to take loans for the weddings. “Every single day since last year, at least three girls undergo gauna because it turns out to be cheaper in the lockdown,” said Bharti. Gauna is a practice in which an already wedded minor is sent to her in-laws’ home after she attains puberty.

Moreover, strict lockdowns have affected the informer network, the backbone of social activism. “People took advantage of the fact that there was nobody to stop them from conducting child marriages because informants themselves were cooped up indoors,” said Bharti. “We only got to know about the marriages after they had happened. With courts shut and access to mentors broken, children have nobody to turn to.” As per government data, the number of child marriages in the first year of the pandemic went up by 33 per cent as compared with 2019.

Jitendra, who works with Childline in Mumbai, agreed that child protection has been compromised during the pandemic. Nine Childline units work at the city level and five at railway stations to make sure no child gets trafficked or abused. But shockingly, from this January to June, they have observed “a steep rise” in the number of cases of domestic violence and mental harassment at home. “We have also rescued and rehabilitated 12- to 16-year-old girls who were sent from Sikkim, Assam and Howrah to Mumbai for work as their families found it difficult to make ends meet,” said Jitendra. The girls are presently protected under the Child Welfare Committee (CWC).

While some children are fortunate to find help, others languish and are mutely resigned to their fate. In Delhi's “very marginalised spaces”, 52 of the 400 girls who volunteers from Protsahan spoke to admitted that they had been victims of incest during the pandemic. And they also said that there was nothing they could do about it because their mothers were financially dependent on the fathers and to protest would mean going hungry and homeless. “Hunger has become a massive issue here,” said Kapoor. “Children have no food and in order to be able to have something on the plate by the end of the day, they must do whatever they are asked to.”

Nutrition, too, has taken a hit. According to a report released by the UNICEF, more vulnerable children are becoming malnourished due to the multiple shocks created by the pandemic and its containment measures. An additional six million to seven million children under five may have suffered from wasting or acute malnutrition in 2020 and disruptions to service may have resulted in 160 million children under five missing a crucial dose of Vitamin A, read the report.

The catastrophic impact of the pandemic has led families to break down and remain irreparably divided, leaving little children to suffer, stripping them off parental love and the emotional, psychological and physical support that comes with it. Take the case of two siblings, Anushka, 9, and Rahul, 11, who lived with their parents and grandparents in a modest house in Lonavala near Mumbai. Last October, they lost their father to Covid-19. A few days later, their mother died by suicide. In less than a week, the siblings became orphans. They are now placed in a Child Care Institution in Pune's Pimpalgaon. They are yet to come out of the shock that their parents are no more, said Subhash Bongarde from CCI, Pune.

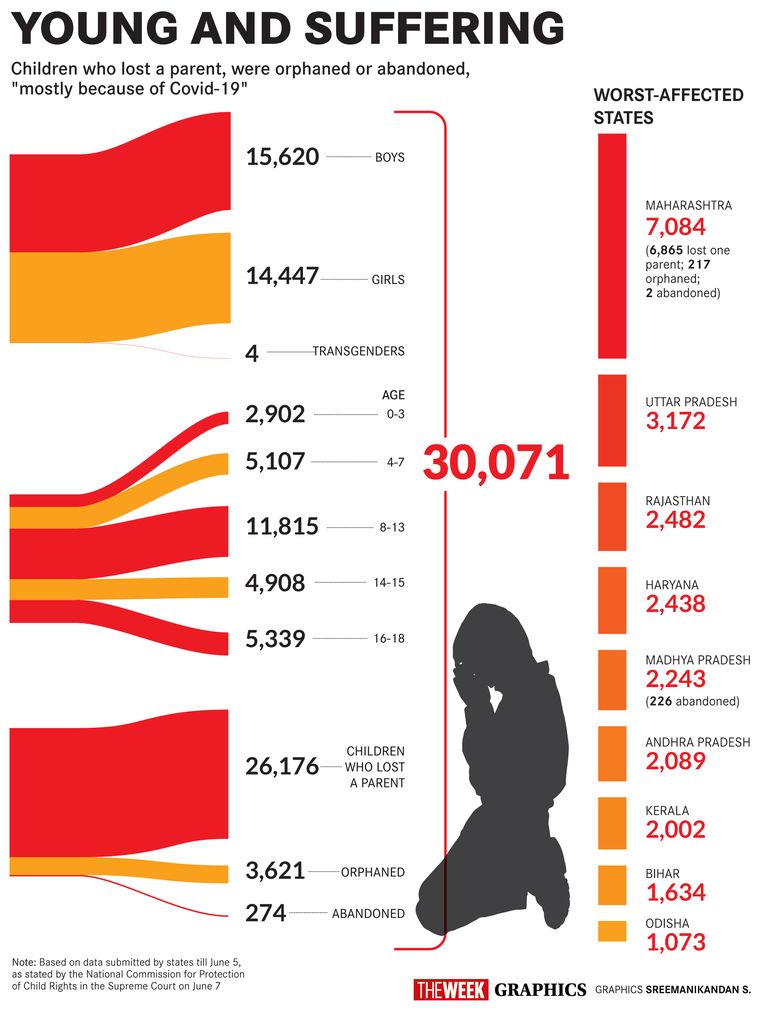

Between April 1 and May 25, 577 children across the country were orphaned after their parents died of Covid-19, said Women and Child Development Minister Smriti Irani, committing to “support and protect every vulnerable child who lost both parents to Covid-19”. For the last six months, a single ward (M-East) in Mumbai has reported 10 cases each month of children who lost either one or both parents to Covid-19. In Maharashtra, more than 5,000 children have lost at least one parent in the last 14 months. Forty toddlers from a single Delhi slum lost their fathers to Covid-19 in the last four months. The second wave has killed more young people, aged 30 to 50, than the first. Take the case of Kerala: 350+ young parents in this age group succumbed to Covid-19 in May alone, and close to a thousand children have lost at least one parent.

In neighbouring Karnataka, a new-born from Mandya district became an orphan even before she could open her eyes. She stayed in the hospital for two weeks as both her parents succumbed to Covid-19 within a fortnight last month. The couple—Nanjundegowda and Mamatha—were preparing to welcome their firstborn after a long wait of nine years. The father died ten days before the baby's birth and the mother five days after. The baby is Covid negative and is presently under the hospital’s care and the supervision of the state's CWC.

The loss of a parent is the most traumatic experience for a child. In Andhra Pradesh’s Guntur district, three children—the youngest being nine years old—became orphans overnight when their mother who was their only parent died of Covid-19. Days later, officials found that the children were living alone in the house, lost and uncared for. A pastor, who has been helping the orphans, is now working with the officials to rehabilitate them. In the same district, Divya, 13, a mentally challenged girl, lost her father to Covid-19 last year and her mother a few weeks ago. She has been shifted to a centre that takes care of children with special needs.

As more and more such cases come to light, so do the challenges of illegal adoption rackets and selling of babies, in some cases by parents themselves in a bid to sail through tough times. In June, the Thane police in Maharashtra reportedly arrested a couple for attempting to sell their sixth child, a five-month-old boy, for 090,000. The father, a rickshaw driver, was struggling to feed his children during the pandemic.

Civil society organisations, health workers, socially conscious citizens and hospitals are all being called upon to report such cases. The government has also widely advertised that people be cautious of any messages on social media or off it that call for adopting such children. One message that was propagated widely in Uttar Pradesh was about two sisters who had been orphaned and were up for adoption. This message caught the attention of the police as the sisters did not even have a gap of nine months between them.

While full disclosures about the guilty have not been made, sources told THE WEEK that the message had been traced to Noida. A post on Dwarka Mom's Group on Facebook, read, “We are interested to adopt a baby girl, age 6 months to 2 years. We arrived at this as you all know in the pandemic situation, many childs (sic) have lost their both parents and nobody is there to look after them. If anyone has some sort of knowledge or contact do share with us.”

On calling the number listed in the post, a man who identified himself as Parag Bhatnagar, who has a small business manufacturing kitchen chimneys in Noida, said he had never approached any formal adoption agency or made inquiries so far even if the itch to adopt a “needy” girl child has always been there, even before the pandemic.

Such posts are now raising the spectre of child trafficking. A week ago, a WhatsApp message was shared in social media groups in Chennai, saying, “Two years baby girl and two months baby boy (Brahmin), in Chennai, have lost their mother and father due to covid. To adopt contact (9xxxxxxxx5).” When Professor M. Andrew Sesuraj, state convener of Tamil Nadu Child Rights Watch, saw the message, he informed social welfare ministry officials only to understand that the message was from Delhi and it was fake. “There are several messages like this. It is true that many children are abandoned at this time of the pandemic. But the question is are they getting the required help and is it addressed through the proper channel,” said Sesuraj.

CWC officials have warned people against directly handing over orphaned children to individuals or NGOs without the knowledge of the government, stating it is a punishable offence under sections 32, 33 and 34 of the Juvenile Justice Act. The Karnataka state police has warned that illegal adoptions can be charged under IPC Section 363 (punishment for kidnapping). Soha Seth Moitra, regional director at Child Rights and You, expounded on the protocol necessary to help vulnerable children find homes and kinship care after losing parents to Covid-19. The CWC first tries to trace guardians of the child. “If the CWC inquiry finds that the child has no one, or is abandoned, it can declare that the child is ‘legally free’ for adoption,” she said. Then, a specialised adoption agency is involved, which conducts a ‘home study report’ of prospective adoptive parents.

The SOS Children's Villages of India, an NGO which has been providing a home for children deprived of parental care, has given shelter to nearly 100 Covid orphans across their 32 villages in 22 states. “The SOS Village has set up a helpline for children who have lost their parents to Covid-19,” said Sumanta Kar, secretary general, SOS Children's Villages of India.

States, too, are lending a helping hand to children who have lost one or both parents to Covid-19. From fixed deposits and bank accounts to education support, district administrations have announced specific measures. In Uttar Pradesh, 565 such children have been identified, and 56 of them are in Lucknow. A stock taking of the numbers happens every evening to ensure that no child slips through the nets. Karnataka’s Women and Child Development Minister Shashikala Jolle has made it clear that only the government can take the custody of the orphaned children.

Yet, can the Central government, with the lowest budgetary allocation for children in a decade at 2.46 per cent, provide for the children, ask activists. “They have taken away our [foreign funding] and other funding sources have been closed,” said the head of a prominent NGO working for child rights in India. “We then get a letter from the Central ministry saying that our volunteers must step into the field to make sure children are well protected and cared for. But how is that possible when we have no money to pay the volunteers?” She added that there are no child protection workers on ground because they were not prioritised for vaccination and they feared contracting the virus.

Ankit Keshri, a PhD researcher and senior research fellow with the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, said that owing to the pandemic, countless children will be separated from their families or family-based arrangements and “placed in harmful environment of closed institutions, causing an increase in institutionalisation”. On the other hand, emergency de-institutionalisation has taken place and with the shutdown of several childcare institutions, children were being restored to families and communities that have no way of supporting themselves. “In India, children were deinstitutionalised without a proper home study or care plan and hardly any follow-up took place,” said Keshri. Experts have also raised doubts over the execution of social distancing and respiratory hygiene practices among children living within institutional arrangements.

Then, there is the issue of children being bullied online. “During online classes, several violations happen when screenshots are taken and circulated. This is scary because now there is no alternative to virtual learning and the options for self-protecting mechanisms remain limited,” said Debarati Halder, a cyber rights lawyer. “Many children who are Twitter users have been trolled for their statements on whether exams should be conducted or not and have actually gone in deep depression. Now their parents have asked them to delete their accounts.”

Even as the country struggles with measures to protect its children, the looming fear of an imminent third wave which is likely to affect children grips the nation. Already, 8,000 children and teenagers reportedly tested positive for Covid-19 in Maharashtra’s Ahmednagar in May alone. These children account for 10 per cent of the cases in the district. “We are taking measures to protect our children. I have personally been doing the recce across districts,” Yashomati Thakur, state minister for women and child development told THE WEEK.

As per the Indian Council of Medical Research’s third National Serological Survey measuring the spread of infection between August and December 2020, 21 per cent of adults and 25 per cent of children in the 10-17 age group showed evidence of past exposure to Covid-19. “Although there is no evidence that children are especially susceptible, due to a large number of persons getting infected, the absolute number of affected children has also increased. Children are suffering from cases of long Covid as well,” said Dr Narendra Kumar Arora, paediatric gastroenterologist and a senior member of the national Covid-19 task force.

Moitra lays down the road ahead, saying that there is a huge need to come up with exclusive children-focused Covid-19 management centres. “We should also try our best to link the family—if there is an extended family or a single parent—with all the social security schemes, because they are long term in nature. There will be a continuous flow of aid,” she said. “And then we should come up with mental health support facilities, because this is the last thing that people think about when it comes to low-income groups. And later on, regular follow-ups by local support systems like panchayats are required.”

Some names have been changed.

With Sneha Bhura, Rahul Devulapalli, Cithara Paul, Lakshmi Subramanian, Sravani Sarkar, Puja Awasthi and Prathima Nandakumar.