AYAANSH GUPTA COULD string together words when he was just one, his parents said. And he could recite mantras when he was two. At three, he does console his mother whenever he notices tears in her eyes. Words have been the lifeline for Ayaansh, who cannot yet sit, stand, chew or even breathe properly. “His speech helped us fight for him. It kept us motivated,” said his father, Yogesh.

In 2019, just before he turned one, Ayaansh was diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). Hyderabad residents Yogesh and Rupal were told that their son would live for only two or three more years. The rare genetic disease affects the central nervous system, severely limiting muscle movement.

The couple had first observed abnormalities when he was six months old. “He had limited movement,” said Yogesh. “He used to get tired in just one or two minutes. We thought it could just be a delay in development. One day, he suddenly lost control of his neck.”

After a mental assessment and a few tests, the neuromuscular disease was diagnosed.

“After the reports came, we broke down in front of the doctors as we did not know what to do,” said Yogesh. “The doctors also conveyed that if we plan to have another child, there would be a 20 per cent chance of the child having the same disorder.”

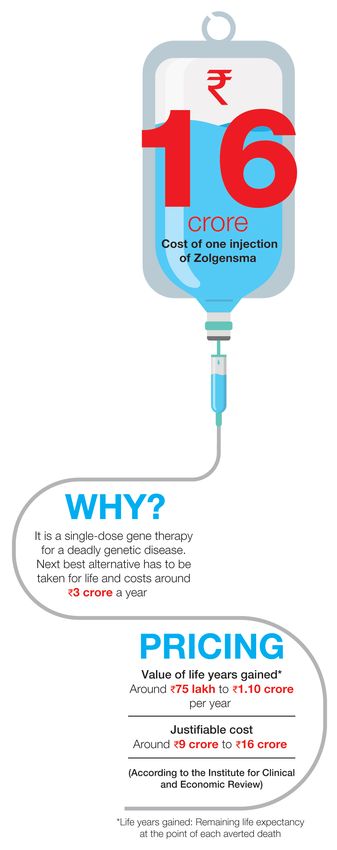

Yogesh, who works for a private equity firm, and his wife, who quit her IT job, dedicated their lives to finding a solution for Ayaansh’s condition. The biggest shock was the realisation that he would need gene therapy involving the world’s costliest medicine—Zolgensma, produced by Novartis, costs about Rs16 crore. Simply put, the single-dose intravenous injection replaces the defective SMN1 gene with a therapeutic gene.

There are two other drugs in the market to treat SMA but they have to be taken lifelong and would cost Rs3 crore to Rs4 crore a year. So, Yogesh and Rupal reached out to support groups and even registered for programmes in which a select few would receive Zolgensma for free. When nothing worked out, the family launched a crowdfunding appeal on social media in February. The target was met by May, with 65,000 donors pitching in.

“My wife was confident that it could be done as she had seen a lot of fundraising campaigns in the US. But I was a little sceptical,” said Yogesh. “We started increasing the visibility and awareness of the campaign. And that is how I think it worked. We used Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn, and also reached out to corporates.”

Celebrities played a big role in popularising the appeal; Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli, Rajkummar Rao and Karan Johar were among the celebs who donated. The campaign also led to the import tax for the drug being waived. The family was guided by Rainbow Children’s Hospital, Hyderabad, which applied for the drug.

Zolgensma is transported at -60°C, and the hospital that receives it must store it between 2-8°C. The drug “is stable for 14 days from receipt” when stored at the prescribed temperature. The cold chain is so critical that Novartis reportedly has an exclusive deal with US-based Savsu Technologies to transport Zolgensma. Savsu’s speciality is “temperature controlled systems and transport containers”. Additionally, it tracks all consignments in real-time through its cloud-based application, evo.is.

Dr Ramesh Konaki, consultant paediatric neurologist at Rainbow Hospital, is one of the few Indians with the training to administer Zolgensma. “Some blood tests needed to be done [before the injection]; one of the samples had to be sent to the Netherlands for antibodies. We could start only if the result was negative,” he said. The result was negative, and Ayaansh was given the jab in the second week of June.

Zolgensma is administered like any other intravenous medicine. Ayaansh was admitted on the morning of June 9. The process took about one-and-a-half hours. He was kept under observation for a few hours and discharged in the evening.

“(The procedure) is exciting because gene therapy itself is revolutionary,” said Dr Ramesh. “It is like nature has taken away a gene from you, and science has reached a stage where you can replace the gene and rectify the genetic difference.”

SMA affects 1 in 10,000 children in India. Among the three types of SMA, babies with type-1, like Ayaansh, rarely survive for more than two years. Those with type-2 and type-3 variants need lifelong, expensive medication to survive. Currently, there are close to 800 SMA patients in the country.

This brings up the question of Zolgensma’s high price tag. Amir Ullah Khan, research director, Centre for Development Policy and Practice, said that currently only the uber-rich in India could afford Zolgensma. He said the government should encourage Indian companies to develop and sell a similar drug at a lower price.

Ayaansh is now back home, and the family is expecting full recovery in seven to eight months. “I never knew there were so many kind souls in the world,” said Yogesh. “When he grows up, I am going to tell him about those who supported him. He will give back to the society that helped him so much.”

There are other heartening stories, too, in the SMA saga, like the one about little Muhammad Rafeek from Kannur, Kerala. The Rs18 crore needed for him was raised in seven days, following an appeal by his parents in late June. Novartis, too, is funding free supplies through its CSR division. In June, four children each received free Zolgensma injections at Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, and at Bangalore Baptist Hospital.