On his maiden two-day visit to India in July, United States Secretary of State Antony Blinken met with top diplomats and Prime Minister Narendra Modi to discuss a range of issues, from Covid-19 and vaccination to human rights and democracy and defence transfers and technologies. However, there was no mention of one significant issue—the sale of the Lincoln House in Mumbai. Earlier this year, when Blinken was up for confirmation as secretary of state in Washington, he reportedly committed to prioritising the resolution of the Lincoln House dispute, which was referred to as “an unnecessary irritant in the bilateral ties” between the two nations.

At the heart of the matter is the lease transfer of the 88-year-old mansion by the US to the Poonawallas, the Pune-based vaccine tycoons, for Rs750 crore. If the transfer happens, it could be the biggest-ever real estate deal in the history of India. But it remains stuck as the Indian government, despite several attempts by US officials, refuses to give its stamp of approval. If there is no headway by the end of this month, the Americans will lose a buyer in the Poonawallas who, as per the contract, can opt out of the deal.

The lease rights for the mansion was first put up for auction in 2011 when the US consulate, which had been occupying it until then, chose to relocate. Three years later, the Poonawallas made a bid and it was touted to be the most lavish real estate deal by an Indian family. As Adar Poonawalla, CEO of Serum Institute of India (SII), reportedly said then, Lincoln House has location, history, size and so it was worth the money. The swanky three-storey mansion, spread across a two-acre plot, is located in the Breach Candy area and has a royal past. The tony locality has a touch of terror, too—opposite the mansion is the Moksh gym, which was reportedly frequented by 26/11 terror accused David Headley while he was in Mumbai scouting for locations for the attacks.

The Lincoln House of today, a grade-III heritage property, is an uninspiring pallid structure, sullied by chipping paint and crumbling walls. A bunch of security guards man the two tall, black gates, but nobody has been assigned the task of looking after its interiors, the guards tell THE WEEK. The nameplate on the right side of the gates is rusting and tilted. Any conversation regarding the property is discouraged and photography is strictly prohibited. Only a tiny window on one of the gates allows a glimpse of the structure inside and thereby a peek into its glorious past—a maharaja’s palace that it once was.

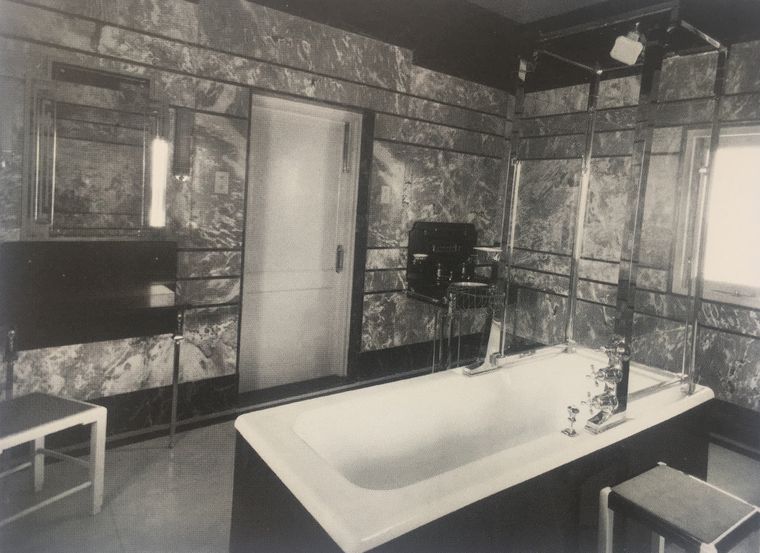

Lincoln House’s history dates back to 1933 when it was called the Wankaner House. It was named so after Maharana Amarsinh Jhala, the last ruler of Wankaner, a former princely state in Gujarat. The maharaja built it as a residential property for close to 40 members. Progressive for his times, he combined the revivalist Indo-Saracenic architectural style with Art Deco interiors across the 50,000sqft palace, presently labelled as a private, heritage property. Around the same time and barely a few kilometres driving distance from Wankaner House, the maharaja designed and built Amar building, which is today one of Mumbai’s most notable landmark—the old Reserve Bank of India building. The royals, belonging to Jhala Rajputs in Gujarat’s Saurashtra, would spend a couple of months in a year at Wankaner House. In 1957, the maharaja decided to transfer the lease rights to the American government (or the US consulate) for a paltry 018 lakh, on the terms of ‘lease of perpetuity for 999 years’.

“It does pinch that such a stellar property was sold off for a negligible amount, but then those times were different,” says Yogini Kumari of Rajasthan’s Sirohi royalty who married Kesrisinh, the scion of the Wankaner royal family, in 2012. “Post-independent India did not allow for the kind of lavish lifestyles we were used to in the British times and the kind of entertainment and hospitality that those lifestyles called for. Hence, it was prudent to get rid of the property at the time.” She further tells THE WEEK that “contrary to what got reported in international media, the upkeep of the palace was never an issue. Right now, the Wankaner palace [Ranjit Vilas palace] in which we live in Gujarat is many times bigger than the Lincoln House and we are still maintaining it beautifully. So, as royals we never tire of the upkeep of our homes.”

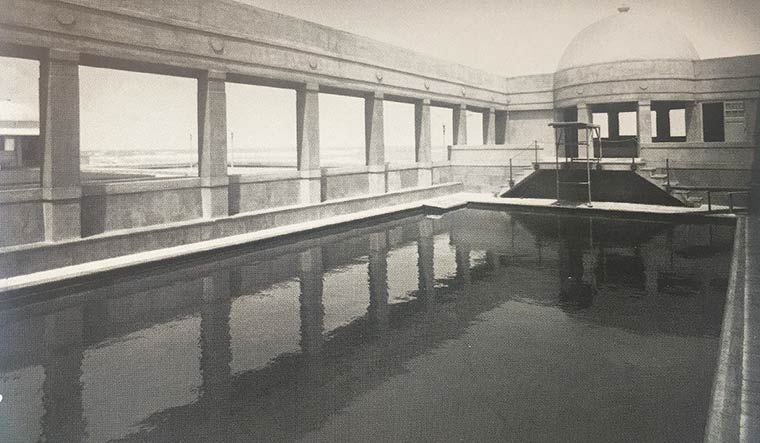

When the Wankaner family resided at the Mumbai palace, it was distinguished for its massive swimming pool that looked out into the sea, two tennis courts, a state cannon, vast manicured lawns and gardens. Of these, only the cannon and the lawns remain. The rest, including the tennis courts, were lost to land reclamation.

Months after the sale of the Wankaner House, Amarsinh bought a number of apartments at the upmarket Altamount Road and distributed them among his cousins. These flats have been all rented out, with the ownership remaining with the royals. The royal family presently resides in Gujarat, where they are involved in diverse areas including education, real estate, stock market and charity. Yogini Kumari and Kesrisinh are hoping to convert the Ranjit Vilas palace into a heritage hotel.

Yogini Kumari last visited the Lincoln House in 2012 with her husband and father-in-law Digvijaysinh, India’s first Union environment minister, just when the consulate had begun to vacate the mansion. “My father-in-law had very good equations with the consul general,” she says. “He would often recall hosting a number of foreign dignitaries, including heads of state and politicians, at the Lincoln House. It was never over for him. The place continued to hold strong emotions even years later.”

When the consulate announced its decision to move out of Lincoln House to a bigger, swankier space in Mumbai’s Bandra-Kurla complex, Lodha Developers made a pitch for it, says Yogini Kumari. The Tata Housing Development Company, too, made a bid. However, development restrictions and regulatory issues stalled the bids. “Things were also stressful at that time because there were talks of the iconic building being completely knocked down. We were all worried,” recalls Yogini Kumari. “But a few years later when Cyrus Poonawalla [chairman and managing director, SII] expressed interest, my father-in-law was very happy because he personally knew Poonawalla; they were friends. Cyrus uncle is a man of great taste and we would be extremely happy if this deal just pushes through and the Poonawallas get it.”

Architect Abha Narain Lambah, too, would like the Lincoln House to go to the Poonawallas. “The architectural significance of the Lincoln House is best expressed in the fact that it was designed by renowned architect Claude Batley, who also designed the Mumbai Central station and other places of historical importance in Mumbai alongside the J.J. School of Arts,” says Lambah, who helped restore some of the most significant landmarks in Mumbai. “But it was built as a private residence, not as a facility of public utility. It was meant for the rich and that is how it should be continued. What is the problem if it continues to be held by another rich family that’s willing to pay for it? It is neither a monument nor a building of public importance, except for its heritage value. Hence it must rightfully be given to the Poonawallas.”

Lambah recalls visiting the Lincoln House for soirees. “They had a lovely upper floor that was used for parties by the consul general, while he resided with his family in the south wing,” she says. “It had a lovely Art Deco style staircase, but most of it is in ruins right now. A wealthy industrialist family that can invest in the upkeep of the building and help the heritage structure survive must be encouraged.”

But the Poonawallas remain silent on the issue. Experts say that the members of the billionaire business family—passionate about thoroughbred racehorses and vintage cars, travel in Ferraris and private jets, and own acres spread across Mumbai and Pune with all properties bathed in opulence—have nothing to lose even if the deal falls through.

In 2019, Adar had reportedly said that the family had paid a substantial portion of the bid amount to the US government in 2015 and called the stalling of the deal “bureaucratic harassment”. He had reportedly blamed the defence estates department of the Union ministry of defence for the deadlock.

As per protocol, since the auction involves a foreign government, the final decision about the property transaction will be taken by the Prime Minister’s Office, say experts. However, both the Maharashtra government as well as the defence estates department claim to be the owners of the land. The ministry of external affairs as well as the ministry of defence declined to comment on the issue.

Meanwhile, with only a month to go, the US government remains steadfast in its appeal to the Indian authorities to speed up the process. In an email interview to THE WEEK, Nick Novak, spokesperson, US Consulate General in Mumbai, said, “With respect to the US consulate property in Mumbai known as Lincoln House, we are working with the government of India to reach a satisfactory agreement to complete the lease transfer of the property.”