On March 24, 2020, when a nationwide lockdown was announced to prevent the spread of Covid-19, lakhs of migrants working in cities began their long walk home. Shortly afterwards, the Supreme Court, hearing a petition seeking relief for the stranded workers, refused to intervene. A bench headed by then chief justice of India S.A. Bobde accepted the government’s submission that not a single worker was on the road.

The same court, in the aftermath of the second wave of Covid-19 this year, directed the Centre and states to provide relief to migrants.

This February 9, a bench comprising Bobde and Justices A.S. Bopanna and V. Ramasubramanian dismissed a petition challenging the constitutionality of the sedition law. A few months later, the top court agreed to examine the same, with Chief Justice of India N.V. Ramana asking the government if the colonial era law was needed 75 years after independence.

In October 2018, a Supreme Court bench headed by then CJI Ranjan Gogoi sought price details of Rafale fighter jets in a sealed envelope from the Centre, raising eyebrows. Recently, hearing a plea of the Election Commission, a bench comprising Justices D.Y. Chandrachud and M.R. Shah batted for transparency by refusing to restrict the media’s coverage of court proceedings. There is a distinct change in the top court’s approach to cases, making experts sit up and take notice.

Concerns about the executive’s looming shadow on the apex court’s functioning tumbled out in January 2018, when four of its senior-most judges held an unprecedented press conference to voice their unease. In the following years, there have been questions on the court’s impartiality, criticism about the manner in which an allegation of sexual harassment against a sitting CJI was handled and outrage over the same CJI accepting a nomination to the Rajya Sabha shortly after retirement.

It is against this backdrop that there appears to be a break from the past. And, the changes coincide with the change of guard in the Supreme Court, with many attributing it to the Ramana effect.

Last year, there had been widespread criticism of the apex court’s stance in the migrants’ case.

High Courts were seen as being more active in dealing with Covid-19-related issues. Eventually, the Supreme Court, under Bobde, began its suo motu hearings in Covid-19 related matters.

After Bobde’s retirement, when a bench of Justices Chandrachud, S. Ravindra Bhat and L. Nageswara Rao began hearing the matter and took the government to task over issues ranging from oxygen supply to its vaccination policy, the government accused the court of judicial overreach.

Additional Solicitor General Satyapal Jain, while disagreeing that courts were overstepping their bounds, did sound a cautionary note. “The court has to see whether the action of the government is within its permissible limits,” he said. “Unless there is a strong mala fide [intention] or the action is arbitrary, the courts should not enter the arena.”

However, the Centre’s U-turn on procuring vaccines is being attributed to the apex court pulling up the government on its vaccination policy.

“The Indian Supreme Court is rated as one of the most powerful courts and it also enjoys a good reputation as a court of justice,” said Prof Ranbir Singh, former vice chancellor of the National Law University, Delhi. “If one would refer to Article 142 of the Constitution, it has inherent powers to grant appropriate relief for doing complete justice.”

And now, there is keen interest in how the top court deals with the petitions filed before it with regard to the politically-sensitive Pegasus snooping controversy.

“Unfortunately, the previous three chief justices—Justices Dipak Misra, Ranjan Gogoi and S.A. Bobde—disappointed the nation,” said Supreme Court advocate Lokendra Malik. “The sequence of events during their tenure was such that the trust of the people in the judiciary was shaken. Be it Covid-19 or human rights, the Supreme Court was not able to work as effectively as many of the High Courts did.”

The Supreme Court’s CJI jinx appeared to claim Ramana, too, just months before he took charge. Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy had alleged that Ramana’s kin had made questionable land deals in Amaravati, the proposed state capital, and that Ramana was interfering in the functioning of the state High Court. However, the judiciary and the bar closed ranks with him. Several members of the legal fraternity wanted Reddy to be hauled up for contempt of court, even as they were disappointed that the Supreme Court’s in-house inquiry report was not made public.

Ramana took charge as CJI on April 23; his tenure will last till August 26, 2022. He has, through his public utterances at events, appeared to set the course for the judiciary. At the recent P.D. Desai Memorial Lecture, he spoke about the need for the judiciary to apply checks on governmental power and action, for which it has to have complete freedom. He stressed on people’s right to protest, saying criticisms and protests are integral to the democratic process.

Experts believe that the CJI came with the task of restoring the credibility of the judiciary, and provide it with a direction.

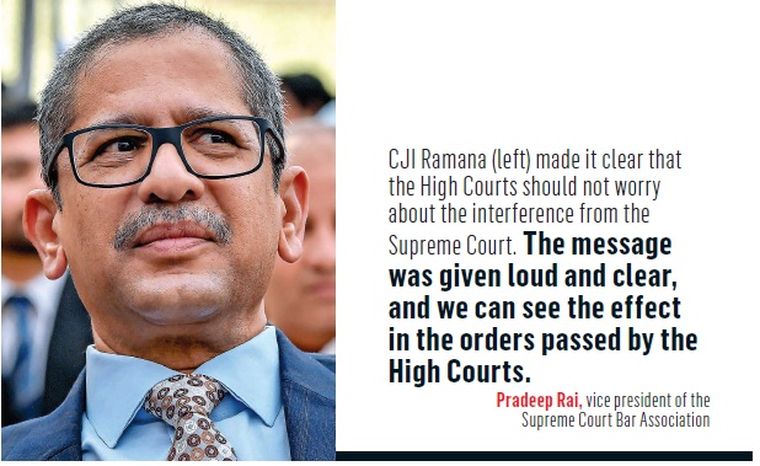

“After taking charge, CJI Ramana made it clear that the High Courts should not worry about the interference from the Supreme Court,” said Pradeep Rai, vice president of the Supreme Court Bar Association. “The message was given loud and clear, and we can see the effect in the orders passed by the High Courts.”

Supreme Court lawyers say that while PILs are being sent to other benches, Ramana is attending to many routine, pending cases, and most importantly, bail matters. Ramana, as a student activist during the Emergency, had to go underground to avoid getting arrested. Experts say that experience has left a mark on him and is reflected in the importance that he attaches to matters involving personal liberty.

It is said that that since he was not flamboyant and did not speak much, everyone had to look to his judgments to gauge what was coming. A bench headed by him held that even when a stringent law like the UAPA has been applied, the accused can get bail when there is no likelihood of the trial being completed within a reasonable time.

Soon after taking charge, as he participated in the discussions to appoint the new CBI director, Ramana cited a Supreme Court order with regard to the selection criteria, which resulted in the government’s favourites getting knocked out. That indicated a change in court-government dynamics.

“I certainly see a perceptible positive change in the views of the media about the credibility of the Supreme Court, after Justice N.V. Ramana took over as CJI,” said former Supreme Court judge Justice R.V. Raveendran. “A change in leadership always gives rise to hope and expectations. I am sure that the present CJI and his successors will steer the Supreme Court in a manner that it is seen as the guardian of the fundamental rights and rule of law.”

As an advocate-on-record in the Supreme Court, Sneha Kalita said that, after Ramana took over, “listing of matters has become much easier, and accessibility of registry officers has improved”.

“The present CJI has shown his deep compassion and concern and is very passionate about [providing] justice to the people,” said Ranbir Singh. “It is hoped that the access to justice will become a reality in the real sense of the term and not be a teasing illusion.”

ASG Jain, however, said that the earlier doubts about the court’s impartiality were unfounded. “The Ram Janmabhoomi dispute was in the courts for the last 70 years,” said Jain. “The Supreme Court took a unanimous decision on the issue. Simply because the decision is not to someone’s liking, that person will say that the court is compromising with the executive.”

Meanwhile, experts say while there are some welcome changes, much more needs to be done. “Many Constitutional matters are pending, such as Article 370, National Register of Citizens-Citizenship Amendment Act, electoral bonds, farm laws,” said Malik.

A radical idea being proposed by Ramana is the setting up of a National Judicial Infrastructure Commission. Experts believe that if he can pull it off, it will shake up the judicial system.

A big challenge for Ramana would be to set the house in order as regards the Supreme Court collegium. Its functioning has, in the recent past, only garnered more criticism—from lack of transparency to the perception that it has compromised on certain names in keeping with the government’s likes and dislikes. The collegium, which had failed to recommend a single name for appointment to the Supreme Court since September 2019 because of internal divisions, recently cleared nine names, including those of three women judges, for the top court. The collegium’s decision was historic as Karnataka High Court judge Justice B.V. Nagarathna stands a chance to take over as the first woman CJI in 2027. However, there are questions about why Tripura High Court Chief Justice Akil Kureshi, higher in the judges’ seniority list than those nominated, has been superseded.

Meanwhile, as judges’ vacancies in the higher courts mount, the wish list of experts ranges from the court standing up to the government with regard to appointments to building bridges to smoothen the differences with regard to the Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) on judicial appointments.

As of June 2021, nearly 40 per cent of judges’ positions in the higher judiciary are vacant. In the Supreme Court itself, ten of the 34 sanctioned posts are vacant.

Jain said it was wrong to blame the government for the vacancies. “The Supreme Court collegium failed to make any recommendation for the top court for two years. With regard to the High Courts, not more than 40-50 recommendations are pending with the government,” he said.

The CJI has asked chief justices of the High Courts to ensure that the recommendations for judges’ appointment to the courts reflect the social diversity of the country. He has also asked the High Courts to consider names of lawyers practising in the apex court for appointment as judges.

However, even as the collegium has sought to make amends by recommending three women judges for the top court, there is immense dissatisfaction over the collegium’s failure to appoint more women judges to higher judiciary. “Women deserve better representation in all courts,” said Malik. “It is the responsibility of the Supreme Court collegium to ensure timely elevation of women judges to the higher courts.”

Surya Prakash B.S., fellow and programme director at DAKSH, said that the collegium system is in need of an overhaul. “The court should begin by making the MoP public,” he said. “It should set up a secretariat, which will receive applications and process them, doing the necessary analysis to evaluate them. The secretariat’s findings can be recommended to the collegium, which will then take the final call.”

Senior advocate Vikas Singh, who also heads the Supreme Court Bar Association, wants mentioning of urgent matters. “I strongly feel that for the Supreme Court to be alive to the problems of the common man, mentioning of urgent matters and physical hearing has to resume,” he said.

Ramana recently quoted English judge Lord Denning to say: “The best judge is one who is less known and seen in the media.”

But the soft-spoken judge has made himself heard loud and clear.