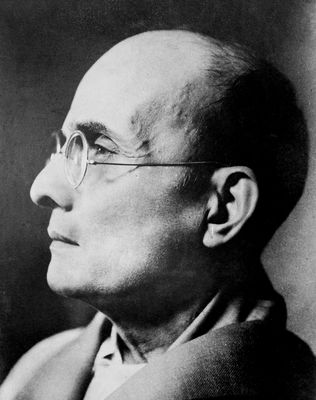

The legacy of a man as contested and polarising as Swatantryaveer Vinayak Damodar Savarkar becomes an issue of contemporary politicking and raucous debate. In all this melee the real picture of the man, his life and philosophy get sadly obliterated, as I was to discover in my five-year-long journey into understanding the many complexities of his character.

As a young man, hailing from Nasik in Maharashtra, Savarkar took to revolutionary thoughts early in life, being influenced by the Italian revolutionaries Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi. Barely in his teens and being deeply moved by the execution of the chivalrous Chaphekar brothers of Poona who had assassinated oppressive British officials, Savarkar established India’s first secret society—the Mitra Mela, which later became Abhinav Bharat—and facilitated a fantastic network of revolutionaries across India. Under the leadership of Tilak, he organised the first-ever bonfire of foreign clothes as a student in Poona’s Fergusson College in 1905, protesting against the Partition of Bengal. He was fined and rusticated from college hostel for this.

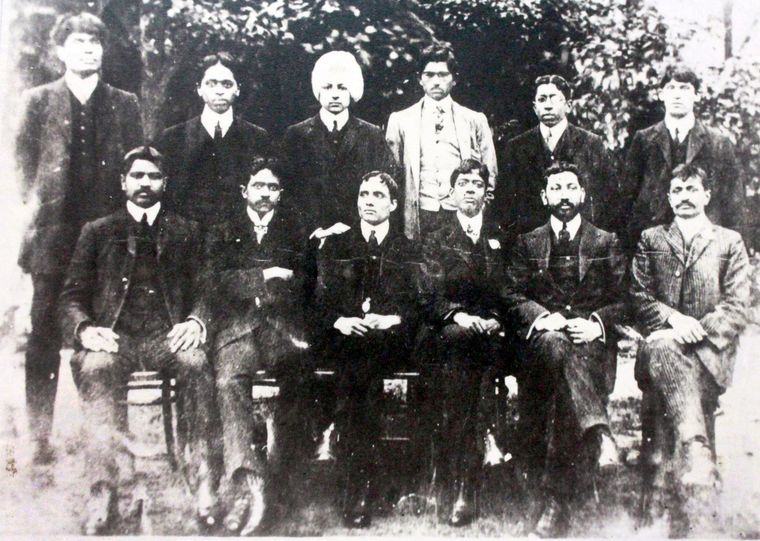

Later, on Tilak’s recommendation Savarkar moved to London on a scholarship awarded by Shyamji Krishna Varma, ostensibly to study law at the Gray’s Inn. But while in London, he became the nucleus of a vast intercontinental, anti-colonial armed struggle to free India. From India to Europe, and even America, a network of brave-hearts guided by him made contacts with Irish, French, Italian, Russian and American leaders, revolutionaries and the press to bring British India and the misery of Indians to the forefront of global discourse. No doubt, the British Government categorised him as one of the most dangerous seditionists. Along with luminaries such as Madame Bhikaji Cama, Sardarsinh Rana, Madan Lal Dhingra, V.V.S. Aiyar, Niranjan Pal, Virendranath Chattopadhyay, Lala Hardayal and M.P.T. Acharya and others, Savarkar spearheaded numerous revolutionary acts ranging from procurement and smuggling to India of bombs, pistols and bomb manuals to orchestrating political assassinations of the British both in India and in the heart of the Empire—London.

Parallelly, Savarkar created a vast intellectual corpus for the revolutionary movement by penning the biography of Mazzini and a well-researched, definitive magnum opus on the 1857 uprising. Terming it ‘The First War of Indian Independence’, he sought to elevate the importance of an event, hitherto disparaged as being a mere Sepoy Mutiny. This book was to serve as an inspiration for revolutionaries decades after it was written—from Bhagat Singh to Rash Behari Bose and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and his INA.

The British were determined to extradite Savarkar to India at all costs. Slapping an unfair Fugitive and Offenders Act (FOA) of 1881, he was deported to India and tried with no right to appeal or defence. He was sentenced to two life-imprisonments totalling 50 years and packed off to rot in the Cellular Jail of the Andamans, where he suffered the worst punishments. Fettered in chains, flogged, condemned to six months of solitary confinement, made to extract oil all day being tied to the mill like a bullock, punished with standing handcuffs for days on end, denied the most basic human needs of toilets or water and fed with foul food that had pieces of insects and reptiles—horrific Kala Pani was indeed the Indian Bastille.

The bogey of the clemency that he sought while at the Andamans is often invoked to discredit him. But these petitions were a normal route available to several political prisoners (including important revolutionaries such as Barin Ghosh, Nand Gopal, Hrishikesh Kanjilal, Sudhir Kumar Sarkar or Sachindra Nath Sanyal who availed the same). Savarkar was also acting as a spokesperson for other prisoners in his petitions where he seeks a general amnesty for all, especially after the First World War and demands clarification of the position and relief that a political prisoner could legally claim. For instance, in his 1917 petition he states: “If the Government thinks that it is only to effect my own release that I pen this; or if my name constitutes the chief obstacle in the granting of such an amnesty; then let the Government omit my name in their amnesty and release all the rest; that would give me as great a satisfaction as my own release would do.”

British Home Department officials like Sir Reginald Craddock who interviewed Savarkar opined that the latter “cannot be said to express any regret or repentance”for whatever he did. “So important a leader is he,”Craddock noted, “that the European section of the Indian anarchists would plot for his escape which would before long be organized. If he were allowed outside the Cellular Jail in the Andamans, his escape would be certain. His friends could easily charter a steamer to lie off one of the islands and a little money distributed locally would do the rest.” The Government obviously rejected his petitions and nothing changed for Savarkar.

Sachindra Nath Sanyal in his memoirs reveals sending identical petitions as Savarkar and being released while Savarkar and his elder brother Babarao were still imprisoned since the Government feared that their release would rekindle the fizzled revolutionary movement in Maharashtra. Moreover, the entire issue of petitions was not some new discovery made in recent times, as is made out to be. Savarkar was not the first, nor the last, to file petitions. Also, he had mentioned these candidly in his own prison memoirs ‘My Transportation for Life’ and his letters to his younger brother Narayan Rao.

From his prison confines Savarkar had watched with horror the dangerous fire that Gandhi was stoking by linking religion with politics through his Khilafat agitation and yoking it to Indian freedom. By promising support to Indian Muslims to re-establish a pan-Islamist Caliphate in Turkey that the British had won in the First World War, Gandhi had sought to receive Muslim support for the non-cooperation movement. But this agitation was doomed to failure as the British were not obliged to listen to the demands of their colonies. The inevitable failure of the movement resulted in widespread clashes across India all through the 1920s—the Moplah incident in Malabar, Gulbarga, Kohat, Delhi, Panipat, Calcutta, East Bengal and Sindh to name a few. Each time, Gandhi’s lukewarm response and the pusillanimity of the Congress angered Savarkar. In this backdrop Savarkar wrote his treatise on Hindutva in 1923, as a direct response to Gandhism and Khilafat. He called for unifying Hindu society and challenged trans-national loyalties through his definition of India’s sacred geography and territorial integrity. Anyone who considered this land as the land of his ancestors and their holy land (including Muslims and Christians) was a ‘Hindu’—not by its religious term, but as a cultural marker of shared common history and bloodline. From then on, Savarkar fashioned himself as the champion for the cause of the Hindu community, though he did not care much for the ritualistic aspects of the religion itself, being an agnostic and rationalist.

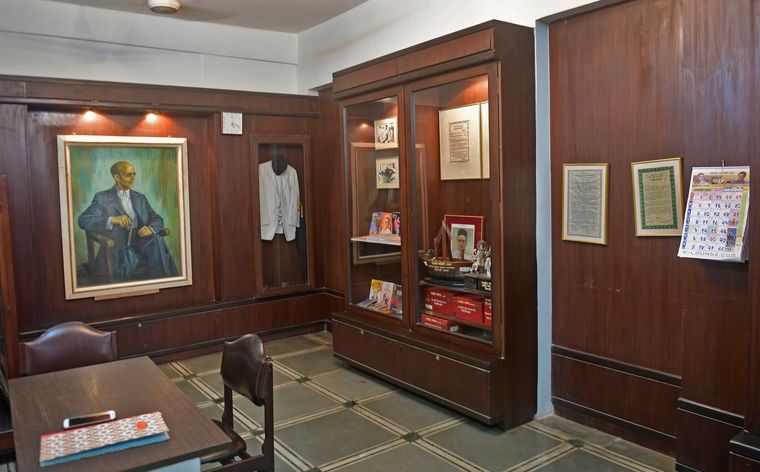

From 1924 to 1937, Savarkar engaged himself in massive social reforms in Ratnagiri where he was kept in conditional confinement after being released from prison. He strove hard for unity in the Hindu society advocating a complete eradication of the caste system, varna tradition and untouchability, and championed inter-caste dining, inter-caste and inter-regional marriages, widow remarriage, female education and temple entry for all castes. His views were more in sync with those of Ambedkar than with Gandhi’s on matters of caste. Savarkar’s degrees were snatched away from him; his property confiscated. Like a few other revolutionaries in Bengal who were given a sustenance income, the Government gave him a pension of Rs60 per month between 1929 and 1937 as he had no source of livelihood.

In 1937, after being released, he took over as the president of the hitherto decrepit All-India Hindu Mahasabha. On the one hand he countered the Congress’s abject appeasement policy and on the other the divisive politics of Jinnah and the Muslim League. His party was the one that opposed the partition of India till the very end. The Constitution of free India, according to Savarkar, was to be one where equal rights and obligations were conferred on all people irrespective of caste, creed, race and religion. “We want to relieve our non-Hindu countrymen,” said Savarkar, “of even a ghost of suspicion that legitimate rights of minorities with regard to their culture, religion and language will be expressly guaranteed.” Quite erroneously he is often described as the progenitor of the dubious Two-nation theory, which actually went back to the 1880s and the times of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. Savarkar opposed the militant groups within the Muslim community and alluded that, given the imagination of a pan-Islamic ummah under a common Caliph, many Muslims did think of themselves as being a separate entity. But he for one opposed the creation of Pakistan or a nation within a nation on religious terms.

Like several other leaders of the time, from Maulana Azad to Ambedkar, who were opposed to the Quit India Movement being launched with no clear plan of action and at a time when the Japanese were threatening to invade India at the height of the Second World War, Savarkar too disapproved of it. He instead encouraged youths to enlist in the British Army, get trained and then defect to Netaji’s INA. That was more likely to win India her freedom, he believed, than jail-filling agitations. The Mahasabha also formed coalition governments with non-Muslim League Muslim parties such as the Krishak Praja Party in Bengal and the Unionist Party in Sindh to split Muslim public space. A brief alliance with the League in government went awry. Of course, in these crucial years leading to partition and freedom, the failure of Savarkar as a leader also comes through; as someone who could not even control the warring factions within his own party or present a cogent alternative to the Congress.

Shortly after freedom, Savarkar was arrested on the suspicion of being complicit in Gandhi’s murder since the main assassins Nathuram Godse and Narayan Apte had been his acolytes in the Hindu Mahasabha earlier. He was arrested and the Red Fort Trials went on in Delhi for over a year. In his testimony in court Godse, however, said: “It is not true that Veer Savarkar had any knowledge of my activities which ultimately led me to fire shots at Gandhiji.” Godse, in fact, spoke about being disillusioned with Savarkar’s pacifism after 1945 and that he decided to break away from him. The edifice of the prosecution’s case stood on the statements of the police approver Digambar Badge’s claims that he, along with Godse and Apte, had visited Savarkar, who wished them success in the conspiracy. The police also got coercive statements from Savarkar’s secretary Gajanan Damle and bodyguard Appa Kasar as being witnesses to this meeting. Curiously, Damle and Kasar were not even brought to court by the prosecution despite their statements being the supposed clincher of Savarkar’s crime. Justice Atma Charan eventually exonerated Savarkar of all charges and interestingly, Nehru’s Government did not appeal against the acquittal.

The Jeevan Lal Kapoor Commission, which was set up closer to the time of Savarkar’s death in 1966, chose to unilaterally blame him for Gandhi’s murder without, once again, calling upon Damle and Kasar to testify among its 101 witnesses. From maintaining all through that a Savarkarite faction within the Mahasabha had committed the murder, it jumped to the abrupt conclusion that Savarkar was responsible for it without any corroborative evidence.

And it is this contentious legacy of Savarkar that gets dragged into contemporary political feuds and toxic electoral discourse. Whether or not to give him a Bharat Ratna posthumously raises huge hackles. On his death in 1966, the then prime minister Indira Gandhi praised him by stating that “his name was a by-word for daring and patriotism” and that “he was cast in the mould of a classic revolutionary.” She got a stamp issued in his name, a film made on his life and her private money donated to a memorial. The question that today’s Congress needs to answer is why their tallest leader would be endorsing a man whom they love to call a British stooge, coward, Islamophobe and Gandhi’s assassin. The sooner we extricate characters of the past from the hurly-burly of today’s politics, the better justice would be meted out to history.

Dr Vikram Sampath is a historian, author of a two-volume biography of Savarkar—Echoes from a Forgotten Past & A Contested Legacy—and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, UK.