Deepika Gurjar has an innocent face and the mischievous eyes typical of a 16-year-old. A class 11 science student from a village near Ajmer in Rajasthan, Deepika is a talented footballer who was selected for a national coaching camp in Bengaluru last November. She is part of a girls’ team set up by the NGO Mahila Jan Adhikar Samiti (MJAS). “I want to become an international footballer,” she says, her eyes shining.

Her elder sister Sapna, 18, is the captain of the MJAS team, and idolises former Indian cricket captain M.S. Dhoni. An undergraduate arts student, she wants to be an IAS officer and a football coach, given that there are not many female coaches in Rajasthan.

Talking to these confident teenagers with such definite goals in life, it is difficult to imagine that both were married off this May 2. Though MJAS encourages girls, mostly from traditional families, to break gender barriers and helps them stave off early weddings, the sisters could only fight for so long. They had managed to stall their weddings, scheduled in May 2021, but had to bow to family pressure this year. With the world opening up after the Covid-19 pandemic, pending weddings, including those of minors, are being conducted in a hurry.

“Our family has promised that our gauna (formal send-off to the groom’s place at the proper age) will not be held for some years and we will be allowed to pursue our dreams. We would like to believe that the promise would be kept,” says Sapna.

In Uttar Pradesh’s Varanasi, Deepti, now 19, was married off to a 31-year-old in November 2020. She had resisted, but her father told her that he could not take care of her and her elder sister (also married off along with Deepti) because the pandemic had left him poorer.

Before she could come to terms with her mother’s death—she had succumbed to Covid-19 in mid-2020—Deepti was in an alien home. And there started a nightmarish phase. Her husband and his family were suspicious of her “character” and resented her tendency to talk back; they abused her physically and verbally.

So, Deepti, not yet 18, returned home within six weeks. It was hardly a warm welcome, but she stood firm and did not return to her husband. Soon, with help from the NGO Shambhunath Singh Research Foundation, Deepti began reclaiming her life. She has passed her class 12 exams and wants to join the police. “The condition at home is bad and I have fallen back to weaving air-cooler panels to earn money. But I am determined to get to a better position in life,” she says.

K. Silamma could not stand up to her family like Deepti. This May, the 16-year-old in Telangana’s Nagarkurnool district was caught in a “trap” that she thought she had escaped last year. The NGO Shramika Vikasa Kendram had tried to dissuade her father, an agriculture labourer, but he said the pandemic had broken him financially, and he wanted to marry off his daughter to ease his burden. To avoid further intervention by the NGO, Silamma’s family, on May 4, took her away to another village and got her married surreptitiously.

SVK, which is supported by Child Rights and You (CRY) and works in 52 villages of Nagarkurnool and Wanaparthy districts, had only prevented two of 33 reported child marriages between January and October 2021. And even in those two cases, both girls, including Silamma, were married off this May.

Within the next six months, another 32 child marriages were reported in these 52 villages. “Most of these happened without anyone knowing. Yet, the numbers in the area we cover is quite low compared with other areas in the state,” says SVK project director Y. Laxman Rao.

In April, in one of the rare cases of legal action against child marriages, police booked the parents of two minors in Madhya Pradesh’s Rajgarh district, along with the guests, the priest, the caterers and the cameramen. The groom was 12; the bride, nine.

Rajgarh Childline project coordinator Manish Dangi, who played a major role in getting this FIR lodged, says that, this year, a major upswing was noticed in the number of child weddings, especially around the auspicious occasion of Akshaya Tritiya (May 3). He says that most of those involved said it was because of the lockdowns in the past two years. But he also adds that child marriages had taken place during the pandemic, but most went unreported because of the lockdown.

Several grassroots social organisations say that the pandemic has reversed a lot of good work done on the ground level in the past several years to eradicate child marriages.

TELLING DATA

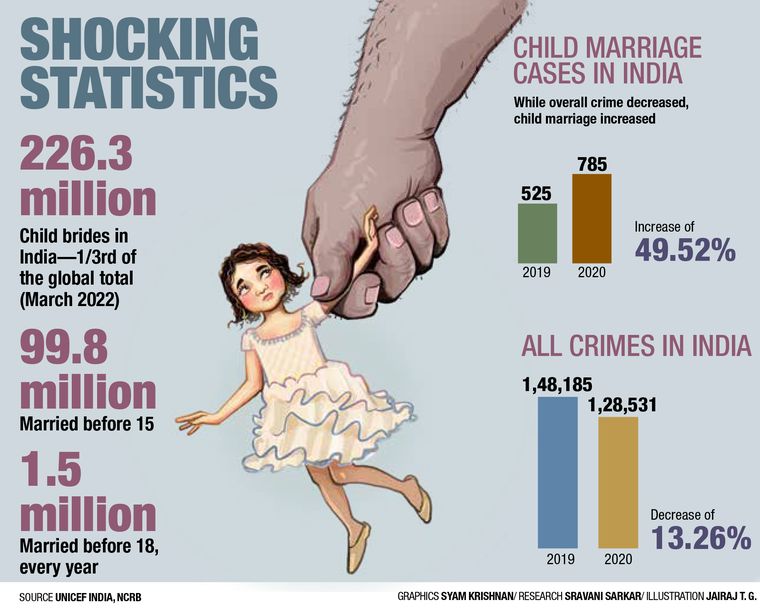

A comparative study of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data of 2019 and 2020 is revealing, says Puja Marwaha, CEO of CRY India. While overall crime in the country dipped 13.26 per cent in the duration, the cases registered under the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006, jumped by 49.52 per cent. Compared with 2015, child marriage cases jumped 167.92 per cent in 2020, she says.

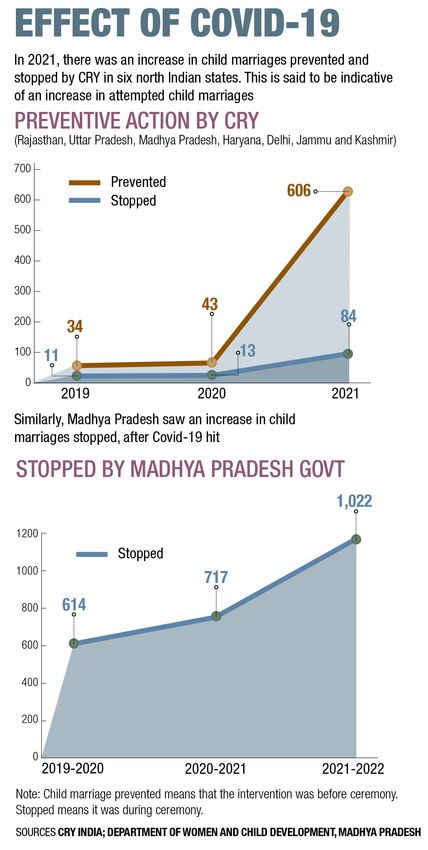

The ground organisations working for CRY say that the higher figures in 2021 (see graphics) might also be because of greater focus on prevention of child marriages after lifting of lockdowns, and that it was clear that there were more attempts to get minors married.

The Bhopal Child Line, run by the NGO Aarambh, along with the police and the department of women and child development (DWCD), stopped 37 child marriages between April 2021 and March 2022. They had stopped 21 marriages in 2020-21, and 20 in 2019-20.

Aarambh director Archana Sahay says that these figures are just the tip of the iceberg. “In our experience, if 100 child marriages are held, we get information of at most 30,” she says. “In urban areas, information about half the marriages planned might be available, but in rural areas, it is difficult to get information on even 10 per cent.”

At the state level in Madhya Pradesh, in April 2022, 192 marriages were stopped and, on May 3, which was Akshaya Tritiya, 51 child marriages were stopped, DWCD data shows.

The fifth edition of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data, from 2019 to 2021, showed a significant dip in underage marriage cases in the past decade. But experts point out that a significant portion of the NFHS-5 data was collected before the pandemic struck, and the rest after the first lockdown period (in late 2020 and early 2021), and may not well represent the impact of the pandemic on child marriages.

Those working in the field say that there was a major reversal of the trend—of child marriage cases going down—because of the pandemic. Laxman Rao says that the child marriage scenario in the villages that SVK works in had returned to the level it was 10 years ago. “The pandemic has hit poor families badly, and the government needs to extend additional social security benefits, ensure local livelihood sources and create good health infrastructure at the grassroots level to give confidence to people that they can survive,” he says.

Madhya Pradesh DWCD director R.R. Bhonsale says that several child marriages were prevented this year, especially during Akshaya Tritiya, because of stricter monitoring through virtual meetings and regular reports from district-level officials. “Though we had no specific feedback on this point, there is a possibility that the pandemic (and consequent easing of lockdowns) might have led to an increase in the ceremonies this year,” says Bhonsale. “However, we were alert in the routine course. We want to achieve a major reduction in the figures.”

WHY WE SHOULD WORRY

The situation in India is in line with the global trend. The UNICEF’s country profile for India, 2020, says, “Across the world over the past decade, the proportion of young women who were married as children decreased by 15 per cent, from nearly one in four to one in five. This means that, over the last 10 years, the marriages of some 25 million girls have been averted.”

However, it adds: “This remarkable accomplishment is now under threat. Over the next decade, up to 10 million more girls will be at risk of child marriage as a result of Covid-19, putting the global total number of girls at risk at 110 million girls by 2030.”

For India, child marriages should be one of the biggest worries, given the huge number of young people it affects. The UNICEF 2022 profile estimated that India has 226.3 million girls and women married before 18, of which 99.8 million were married before 15.

A UNICEF programme brief on ‘ending child marriage and adolescent empowerment’ says: “Child marriage ends childhood. It negatively influences children’s rights to education, health and protection. These consequences impact not just the girl directly, but also her family and community. A girl who is married as a child is more likely to be out of school and not earn money and contribute to the community. She is more likely to experience domestic violence and become infected with HIV/AIDS. She is more likely to have children when she is still a child. There are more chances of her dying due to complications during pregnancy and childbirth.

It further says, “Child marriage negatively affects the economy and can lead to an intergenerational cycle of poverty. Girls and boys married as children more likely lack the skills, knowledge and job prospects needed to lift their families out of poverty and contribute to their country’s social and economic growth. Early marriage leads girls to have children earlier and more children over their lifetime, increasing economic burden on the household.”

THE PANDEMIC’S IMPACT

A CRY policy brief on ‘Combating Child Marriage During Covid-19 and Beyond’ says, “Since economic insecurity is one of the key drivers of child marriage, a fragile social protection system unable to reduce household-level vulnerabilities is a direct contributor to increasing child protection violations as well as child marriages during humanitarian crises (like Covid-19).”

It further says that dysfunctional child protection systems (the systems were severely impacted because of the pandemic) increase risk of gender-based violence and child marriage, physical and emotional maltreatment and psychosocial distress of children. “The pandemic also weakened social structures, which added to anxieties related to girls’ safety within households. In these adverse situations, child marriage is seen as a solution to protect girls for fear of stigma arising from various forms of abuse, including sexual assault,” says the policy brief.

Sahay says that the impact of Covid-19 on child marriages was seen in two phases—one while the pandemic was raging and lockdown was in place, and the other when lockdown was lifted. “During the pandemic, most families, especially of marginalised communities, suffered major livelihood losses,” she says. “Whatever resources they had, they thought it wise to spend on fulfilling important responsibilities like getting their daughters married. The lockdown restrictions gave them the opportunity to organise very small weddings, during which two or three siblings or cousins (irrespective of their age) were married off at once at a very low cost. Another factor—very typically Indian—was the emotional pressure from elders of the family who said they wanted to see their grandchildren married off before something happened to them because of the pandemic. After lockdowns eased in mid-2021, those who had been waiting to get their children married rushed into the ceremonies before restrictions were imposed again. Adolescent girls, who had fallen out of school during the lockdown period, became vulnerable to underage marriages as families were worried about their safety and possibility of them getting into ‘unsuitable’ alliances.”

Indira Pancholi, a social researcher and founding member of MJAS, Ajmer, explains it like this. “We have to understand the centrality of the institution of marriage in the Indian society,” she says. “Everything in life revolves around marriage. Traditionally, society has wanted to control sexuality, reproductive ability and labour capacity of both men and women, and marrying them off at a very young age was the best way of control. When grown up, individuals are liable to make their own choices and society does not want to allow this. So, breaking off the child marriage alliances are heavily penalised, forcing the couple and the families to stick to it.”

As for the impact of Covid-19, she says that when the pandemic was raging, there was a big upswing in early gauna as economic distress and deaths in families required that extra helping hand. “Then when the lockdown was eased, there was a rush of underage marriages,” she says. “This was because adolescent girls sitting at home were considered a big risk. Also, the confidence and power of negotiation of girls reduced as their school routine was broken and there was emotional pressure due to distress in the family. As a result, we noticed a 30 to 40 per cent reduction in girls’ resistance to marriage at an early age.”

BIG CHALLENGE

Rolly Singh, programme director, SRF (Varanasi), says that work to eradicate child marriages, especially amid the distress caused by the pandemic, is challenging because it is a socially accepted tradition and there is resistance to steps taken against it. “It is important to work on root causes leading to child marriages such as child protection (safety of girls), poverty, lack of education and so on. Patchwork approach will not help,” says Singh. “There are many laws and rules, but no effective implementation or monitoring. Adequate dedicated resources through proper planning and budgetary allocation are very important, as are appointment of dedicated decentralised personnel, an implementing and monitoring body and inter-departmental coordination in the government.”

CRY CEO Marwaha emphasises that girls empowered with education are better able to make informed decisions regarding their life and participate in decision-making processes both within the family and outside. “Ensuring education to the girls as a legal right up to the age of 18, universal access to sexual and reproductive health services, addressing societal gender norms and attitudes regarding role of girls and women, and building agency through life-skills education for adolescent girls and boys are some of the key components, which, we believe, can a go a long way in re-scripting the social reality for adolescent girls.

“Creating awareness among girls of the existing socio-cultural norms, and supporting them to change the narrative by growing to their full potential is something that CRY holds very close to its heart. It is extremely crucial that young girls set goals and stubbornly pursue them, come what may. We are sure their grit and resilience will inspire others to break age-old barriers.”

... AND CHILD GROOMS TOO!

While underage marriage of girls has found some focus, there has been little discussion on that of boys. The first-ever analysis on child grooms by UNICEF in 2019 said that an estimated 115 million boys and men around the world were married as children. Of these, one in five children, or 23 million, were married before the age of 15. Girls remain disproportionately affected, but in child marriage-prone states like Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, 30.1 and 28.7 per cent boys, respectively, were married off before the legal age of 21, according to the fifth edition of the National Family Health Survey.

“Child grooms are forced to take on adult responsibilities for which they may not be ready. Early marriage brings early fatherhood, and with it added pressure to provide for a family, cutting short education and job opportunities,” the UNICEF analysis said.

In an Indian context, Pancholi says families want the young couples to bear a child as soon as possible so that the boys could be forced to start earning a livelihood. Naturally, they lose out on education, skill development and socio-economic growth opportunities.

Singh says that along with the above, lack of adequate sex education has a physical, medical and psychological impact on the young grooms. “The boys who earn even a small livelihood are considered a good catch as a groom, irrespective of whether they are mentally, psychologically and physically ready for marriage,” she says.

Also, a big fallout of child marriages is that the boys abandon the girls once they grow up, start earning well and have a choice. “Even if the wives from childhood marriages are accepted,” says Singh, “they are subject to severe domestic violence.”

(Names of all minors changed to protect their identity.)