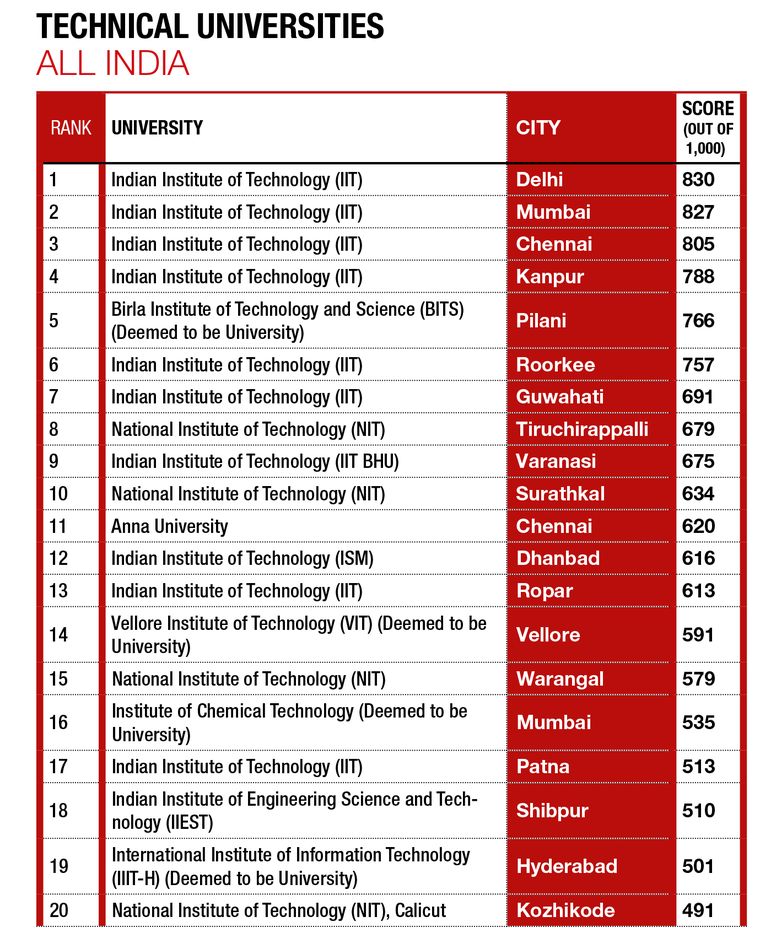

A visit to the Birla Institute of Technology and Science in Pilani is an interesting experience. Pilani is a five-hour drive from Delhi. The town, in Rajasthan’s Jhunjhunu district, is unremarkable. But, the BITS Pilani campus can leave you mesmerised. It is this magnificent campus—a veritable factory of excellence—that has made the small town of around 50,000 people widely recognised.

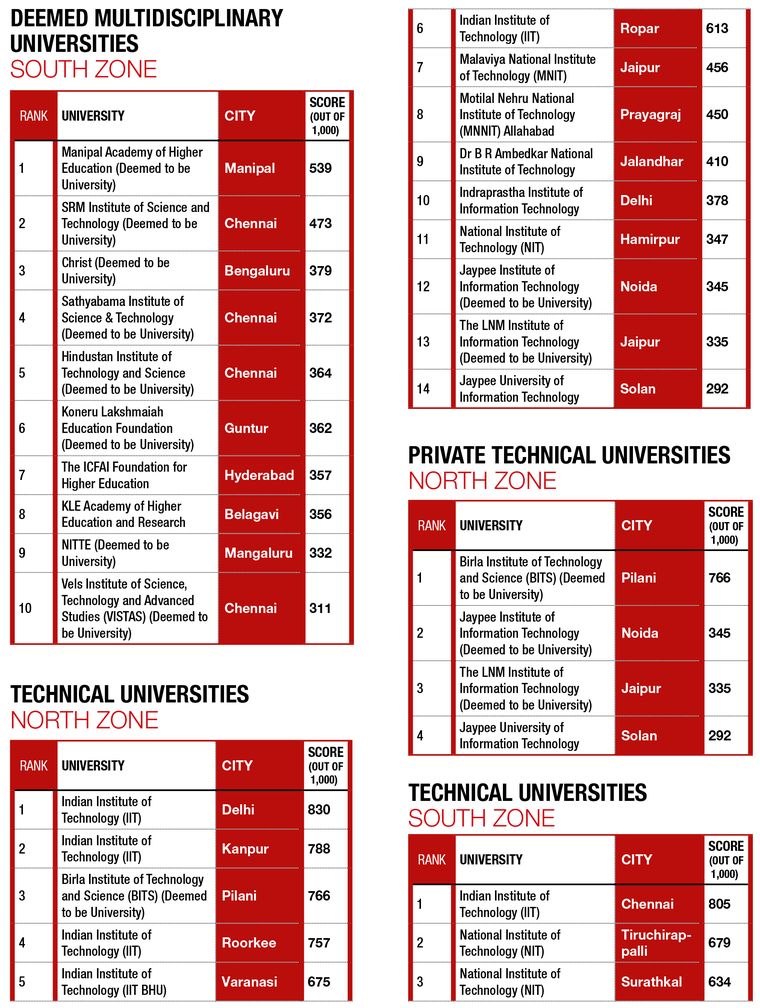

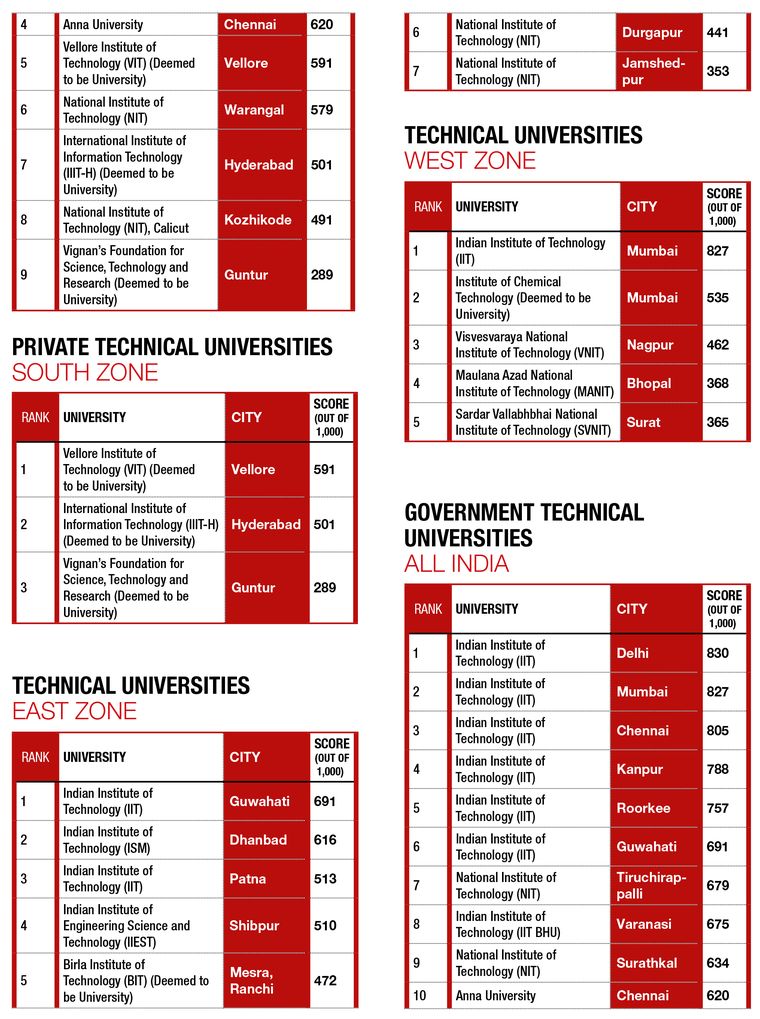

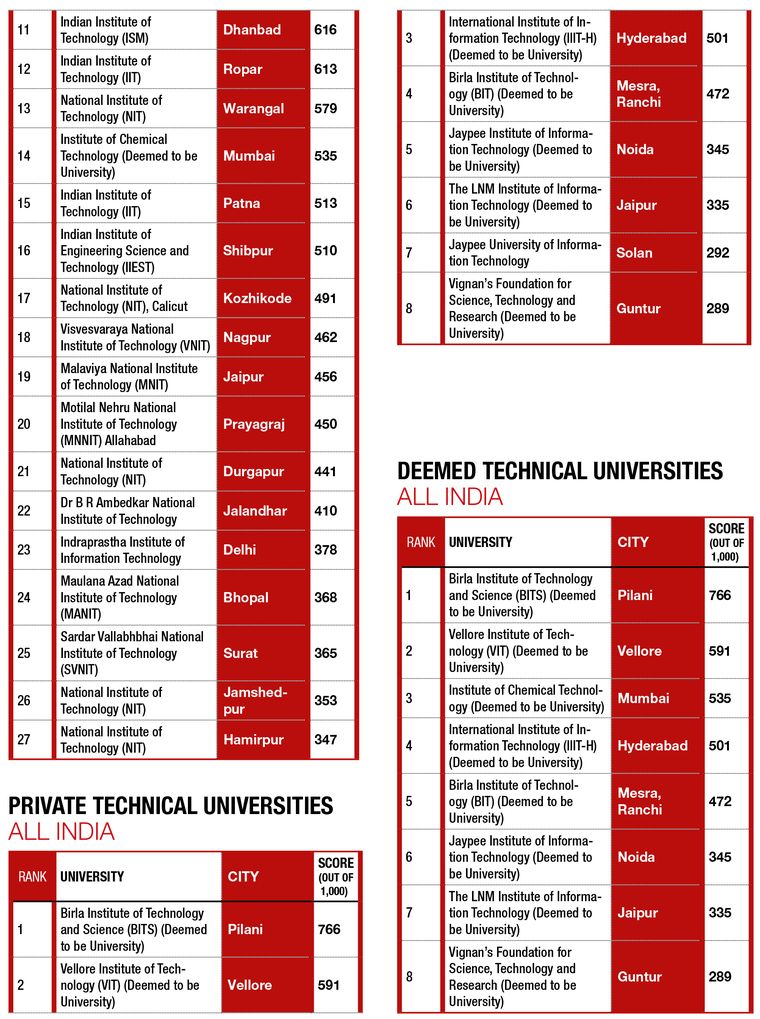

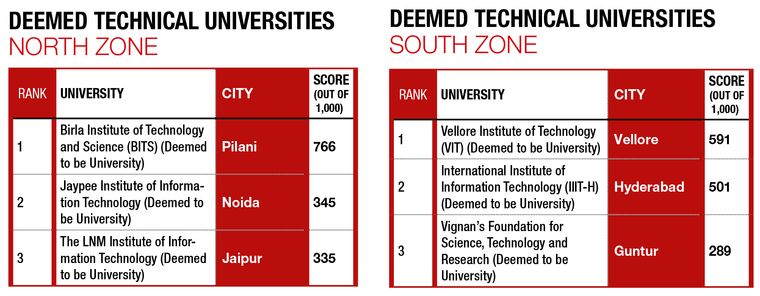

Established in 1964, BITS Pilani, which is the top private technical university as per THE WEEK-Hansa Research Best Universities Survey, 2022, has an alumni network that boasts more than 6,000 CEOs and more than 3,000 academicians, including vice chancellors and directors at prestigious educational institutions across India. BITS now has three more campuses—Dubai (established in 2000), Goa (2004) and Hyderabad (2008). The campuses have identical curricular structures, and, together, have 17,500 students and 935 faculty members.

As we reached the campus, Prof Souvik Bhattacharyya and Prof Sudhirkumar Barai were eagerly waiting to greet us. Bhattacharyya is the vice chancellor of BITS Pilani and Barai is the director of the Pilani campus. Bhattacharyya’s spacious office overlooks the new academic block designed by architect Hafeez Contractor. The vice chancellor puts the new block in perspective: “This campus is a wonderful blend of tradition and modernity.” The balance is not limited to architecture; retaining and building on effective methods and constantly updating where necessary has helped BITS become what it is today.

But, will the time-tested traditions at BITS be affected by the government’s attempt to modernise education through the National Education Policy 2020? Not in the least, says Bhattacharyya, because the kind of norms envisioned by the NEP are not new to BITS. In its early days, BITS Pilani benefited immensely from its association with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Among the key value additions were the development of a modern approach to pedagogy and curriculum design.

Benefits of an NEP-like model

“We provide a curriculum structure with utmost flexibility,” says Bhattacharyya. “For instance, if you are a mechanical engineering student, you can blend it with a management subject, any other technical subject, a data science subject or a language or social science course. Students blend their choices depending on the demands of the market and personal preferences. We are glad to see this being captured in a national policy document, but we, at BITS, have been following this for more than three decades now.”

He adds that the dual-degree programme at BITS can generally be completed in five years. “Typically, an MSc in a science discipline and BE in an engineering discipline are combined, leading to unique expertise blends,” says Bhattacharyya. “The IITs started dual-degree programmes (BTech and MTech in a five-year course) in the late 1990s. I feel that the government and regulators would do well to allow complete autonomy for institutes that are performing well so that they implement quality academic designs based on innovative ideas with contemporary interests, moving away from the prescriptive regulation approaches.”

At BITS, there is a unique industry immersive curriculum design with two “Practice Schools” to give students more exposure. PS-1 is for two months for second-year students to familiarise them with a work environment and give them exposure to problem solving and other functions. PS-2 is in the final year and it is for five-and-a-half months. Barai says that at this stage, the student is almost like an employee. “In some industries, our students have even got a stipend of Rs1.3 lakh per month during their five-and-a-half month stint,” he says. “The median stipend in the last academic year was Rs36,000 per month and the total stipend paid to BITS students was Rs63 crore. We have more than 500 companies connected to the Practice School division.”

Devanshu Sahoo, a third year BE (electrical and electronics) student at BITS Pilani, says that there is a lot of flexibility and freedom. “There is zero per cent attendance requirement,” he says. “In some institutes, you cannot give examinations without an attendance of 80 per cent to 85 per cent. Here, if you feel like not attending a class, you don’t attend. The recordings of lectures are made available.”

Sahoo says he is working on a project for Akshay Cooperative, the supermarket on campus. “I am trying to make Akshay independent of the electrical grid through solar energy,” he says. “We have achieved 80 per cent independence.” It is such a structure that has helped BITS create an innovation ecosystem, which in turn has led to the creation of over 7,000 startups, including unicorns like Swiggy (now a decacorn: $10 billion-plus valuation) and BigBasket (acquired by Tata).

Implementation: Challenges and opportunities

The situation at a large multidisciplinary university is quite different from BITS. For instance, the University of Delhi—India’s third best multidisciplinary university as per THE WEEK-Hansa Research Survey—is responsible for around 80 colleges and more than seven lakh students. So, a visit to the university, which is celebrating its centenary, was warranted to understand the progress made in NEP implementation.

Prof Yogesh Singh, vice chancellor, University of Delhi, works out of a grand office in the historic Viceregal Lodge in Delhi. The building had housed four viceroys—Lord Hardinge, Lord Chelmsford, Lord Reading and Lord Irwin—before it was handed over to the university in 1933.

The vice chancellor says the university is now in the implementation stage of the NEP. “If we do not implement it the way it should be, then the country will not get the fruits of the NEP,” he says. “Implementation is more important than planning and designing of the NEP. In Delhi University, our four-year undergraduate curriculum is ready. We will focus on a multidisciplinary, student-centric approach.”

Under the NEP, says Singh, students who secure admission for the BSc physics (honours) course, can also pursue courses like psychology, based on their interest. “After four years, if one is able to earn 24 credits in the psychology stream, then one can get a major in physics and minor in psychology,” says Singh. “Many international universities are practising this, but, for us, it is a new thing. Another aspect is practice-oriented teaching and how to do it.” Besides this, there is multiple entry and exit.

He says the university was giving a second chance to students who could not complete their degree courses earlier. “So far, we have received 6,000 applications,” he says. “A few people who had registered in the 1970s, but did not complete their degrees, now want to complete.”

As per the NEP, says Singh, students will get undergraduate certificates even if they exit after one year. “If they exit after two years, they will get undergraduate diplomas,” he says. “After the third year, it is an undergraduate degree.” He adds that the University of Delhi gives honours after three years and, after four years, it would give a multidisciplinary degree with a major and a minor. “It is a student-centric approach,” he says. “They are free to decide what they want to study. We are implementing this from this academic year.”

Regarding the controversial CUET (common university entrance test) Singh says that till last year, admissions were based on marks. “But, we have multiple education boards in the country,” he says. “Some are lenient, some are strict. So, there was no uniformity. Hence students studying in a lenient board were getting high marks and some students in strict boards were getting less marks. I feel that when we are admitting students, there should be uniformity. This should be relevant to all students, coming from different backgrounds and regions of the country.”

Vidya Yeravdekar, principal director, Symbiosis Society, and pro-chancellor, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, feels that the NEP is a comprehensive document which defines the true spirit of holistic and all-round development. “Undoubtedly, the NEP has included all aspects of the Indian education system after massive stakeholder consultations,” she says. “The NEP is the most progressive document, not only in India, but also abroad. [Because of] NEP implementation, foreign universities are excited for collaborative higher education opportunities in the sphere of teaching, learning and research.”

She says that Symbiosis International has been a forerunner in imparting multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary education and that students were given the opportunity to earn credits from varied courses of their choice. “With the NEP, it has become focused and institutionalised for us as well as for other Indian universities to strive for holistic transformation of students,” she says. She adds that Symbiosis International has formed eight committees for the effective implementation of the NEP; they deal with aspects like multidisciplinary education, research and innovation, and internationalisation.

The committees, says Yeravdekar, have drafted a robust roadmap which shall be implemented in the coming academic year. “The NEP has paved the way for new global initiatives for students,” she says. “It has provided the opportunity to pick and learn courses as per the interest of the students. By the next academic year, as part of our internationalisation pursuits, we shall launch dual and joint degree programmes in collaboration with global universities.”

Yeravdekar feels that with deemed-to-be and private universities implementing initiatives of the NEP and adapting to changes quickly, the challenge lies in how government universities embrace it flawlessly. “In the coming year, we may face teething challenges in effective NEP implementation,” she says. “However, by 2023-2024, we shall see the actual transformation in the Indian educational system.”

She further adds that post NEP implementation, there will be a sea change in the career moves and job placements of students. “Future workplaces shall prefer multi-skilled and talented all-round professionals with strong interdisciplinary ability,” she says. “Besides technical forte, they lay emphasis on critical, lateral, collaborative and creative thinking skills.”

Research in focus

Despite the ongoing changes in the Indian education sector, research has remained a high priority area for Indian universities. For example, Prof P.B. Sharma, vice chancellor, Amity University, Gurugram, says that the multidisciplinary environment of the university is further supported by a research culture. The university offers more than 108 undergraduate and postgraduate programmes. “Our innovation incubator is supported by the ministry of electronics and information technology and our biotechnology research group is engaged in cutting-edge research in areas of high relevance such as cancer research and infectious diseases, and computational biology,” says Sharma.

Kaustav Bandyopadhyay, who is leading the plant biotechnology group at the university, says: “We are working towards designing a biosensor that can detect the presence of heavy metals like cadmium and arsenic inside a plant in real time without killing the plant. This will help farmers to determine whether there is a chance of contamination in their produce and will save consumers from long-term health concerns.” There is also a nanobiotechnology group that is researching a new method to diagnose diabetes-related complications.

The nanoagriculture group is testing a “quantum dot” which can absorb solar energy. When applied to plants, these dots can provide extra energy to the leaves, which can then convert it into food. Drug research is also high on the agenda, with three groups developing innovative approaches to combat fungal infections, which lead to more than 1.5 million deaths a year.

Sharma says the university also has a herbal drug design and drug discovery centre that has filed 22 patents. “These include a herbal drug derived from Gular tree milk for treatment of liver cirrhosis and migraine treatment from Akara flowers.”

The university also focuses on ocean and atmospheric sciences and has an active collaboration with the NASA Gordon Space Research Centre for monitoring atmospheric aerosol.

Clearly, Indian universities do not lack initiative. The implementation of the NEP could provide even more room to experiment.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

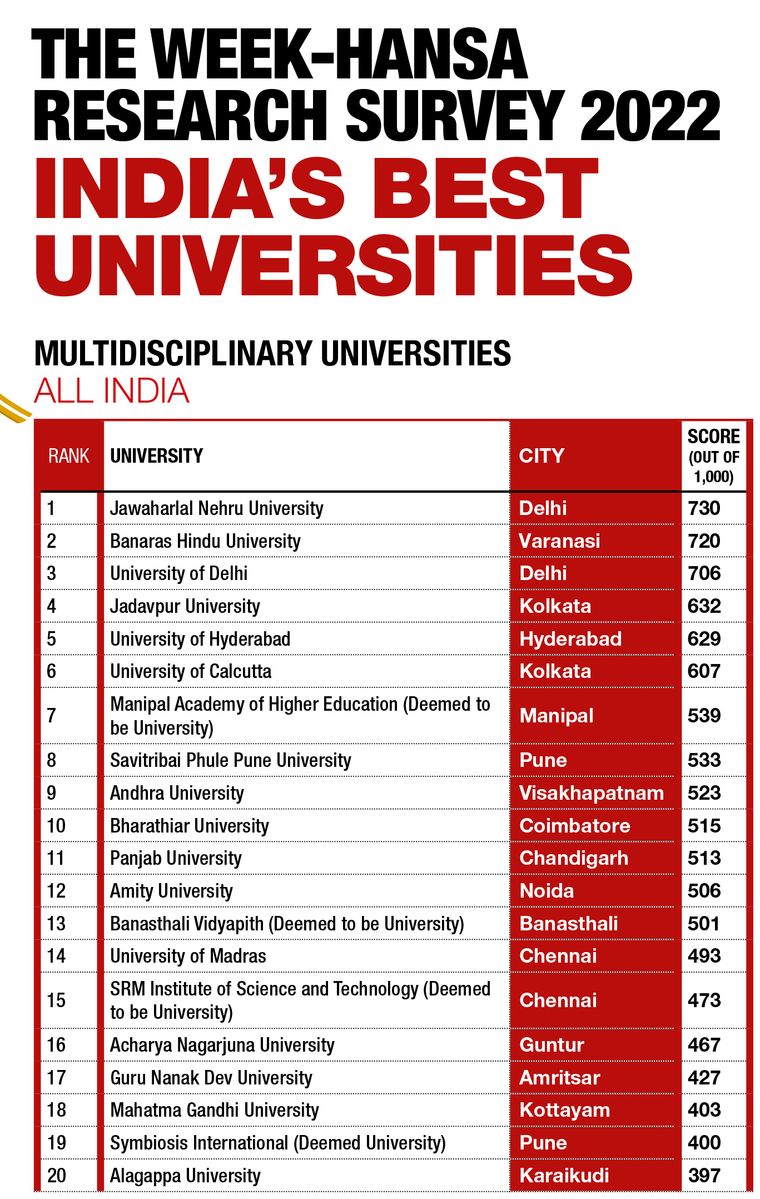

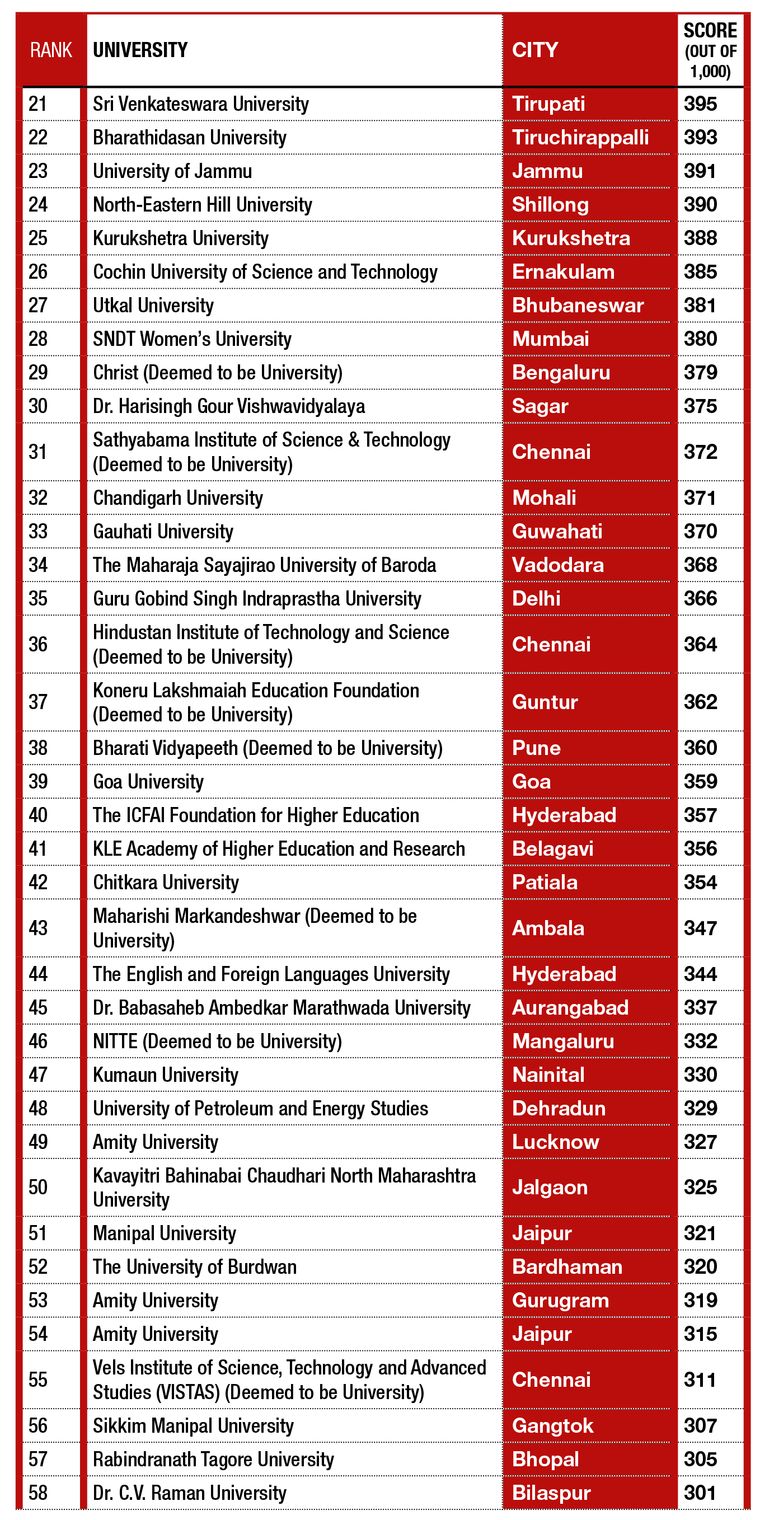

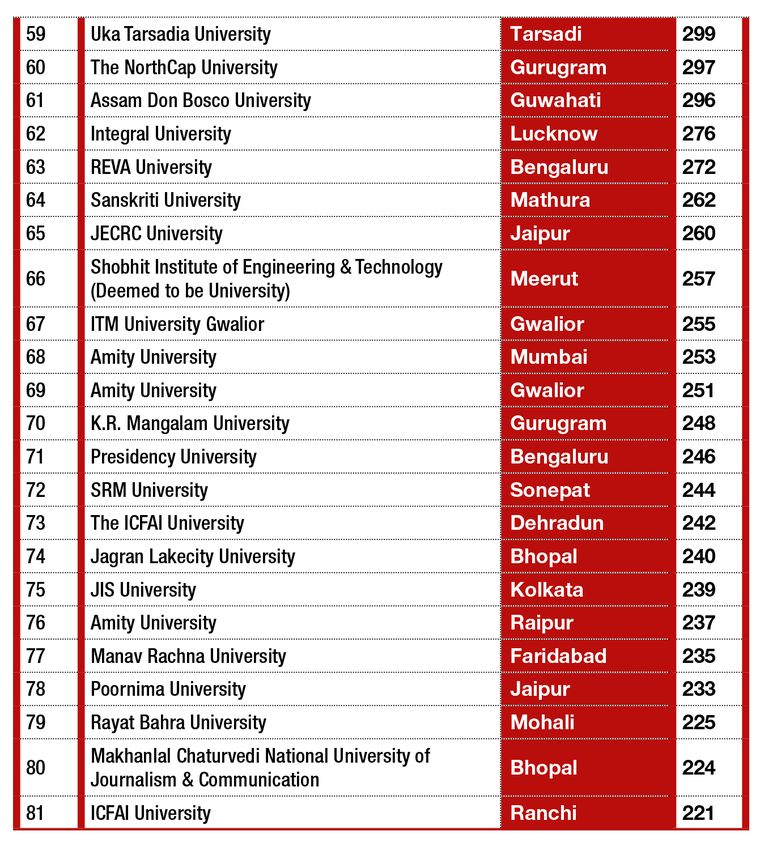

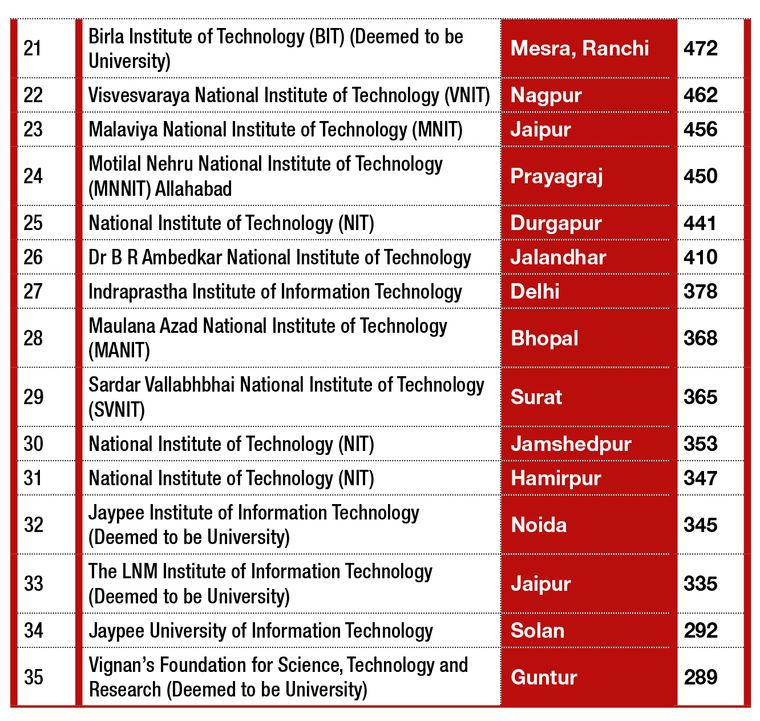

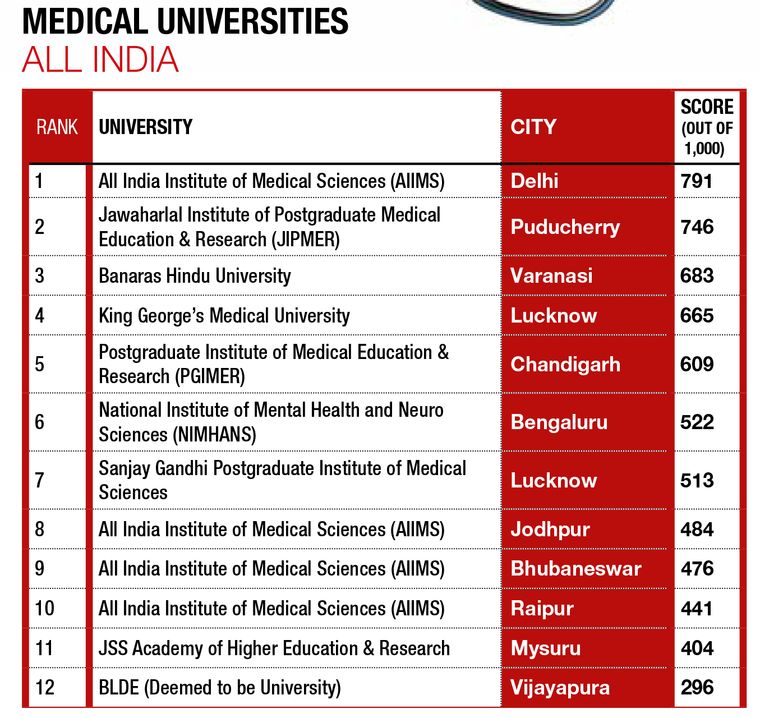

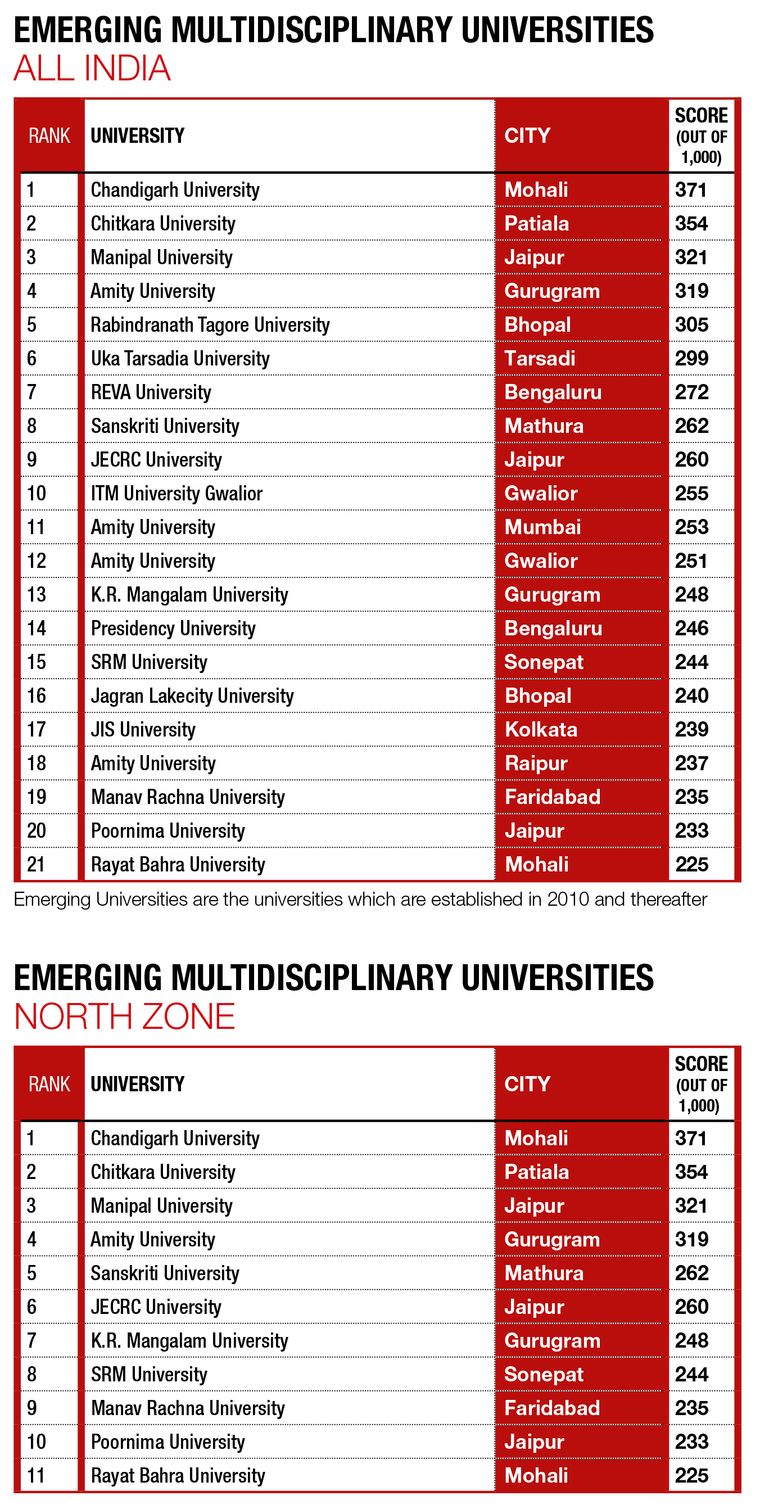

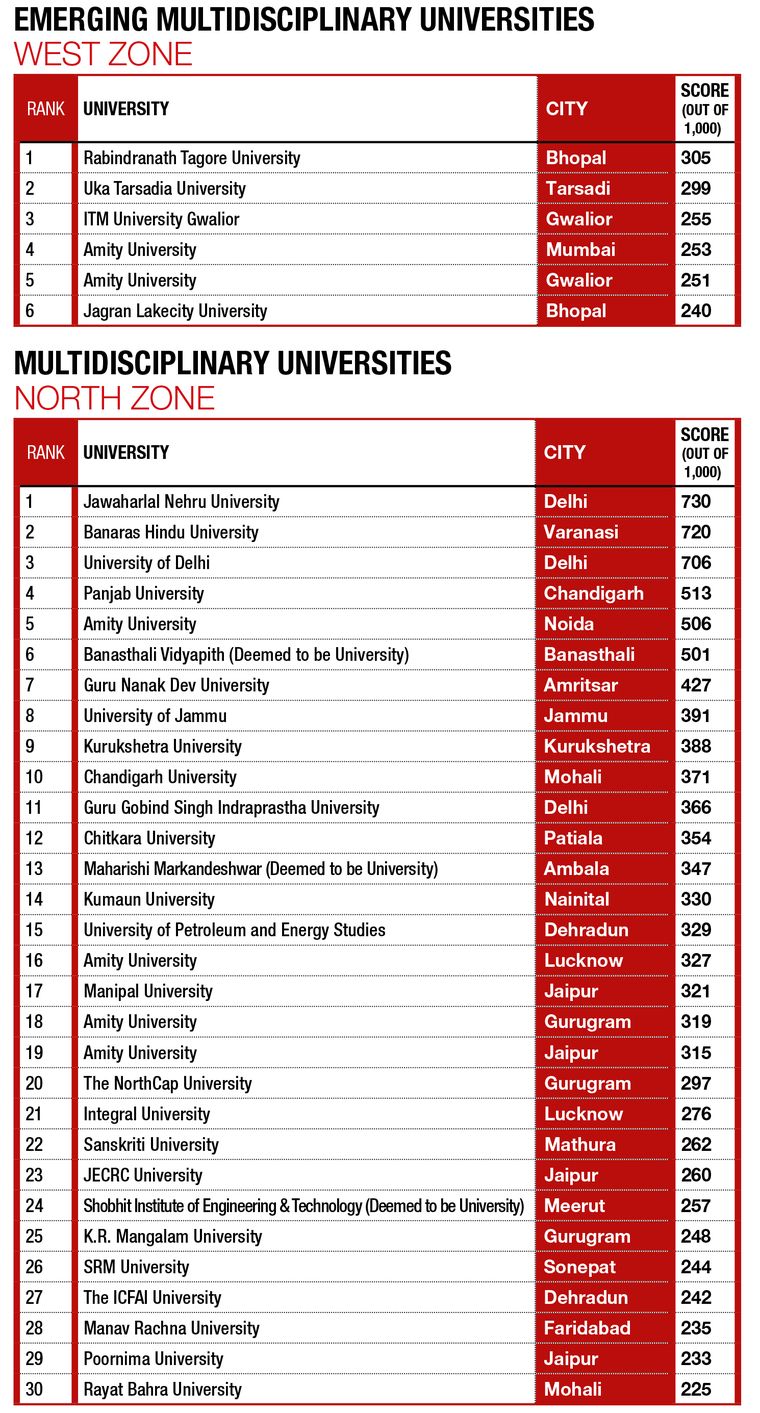

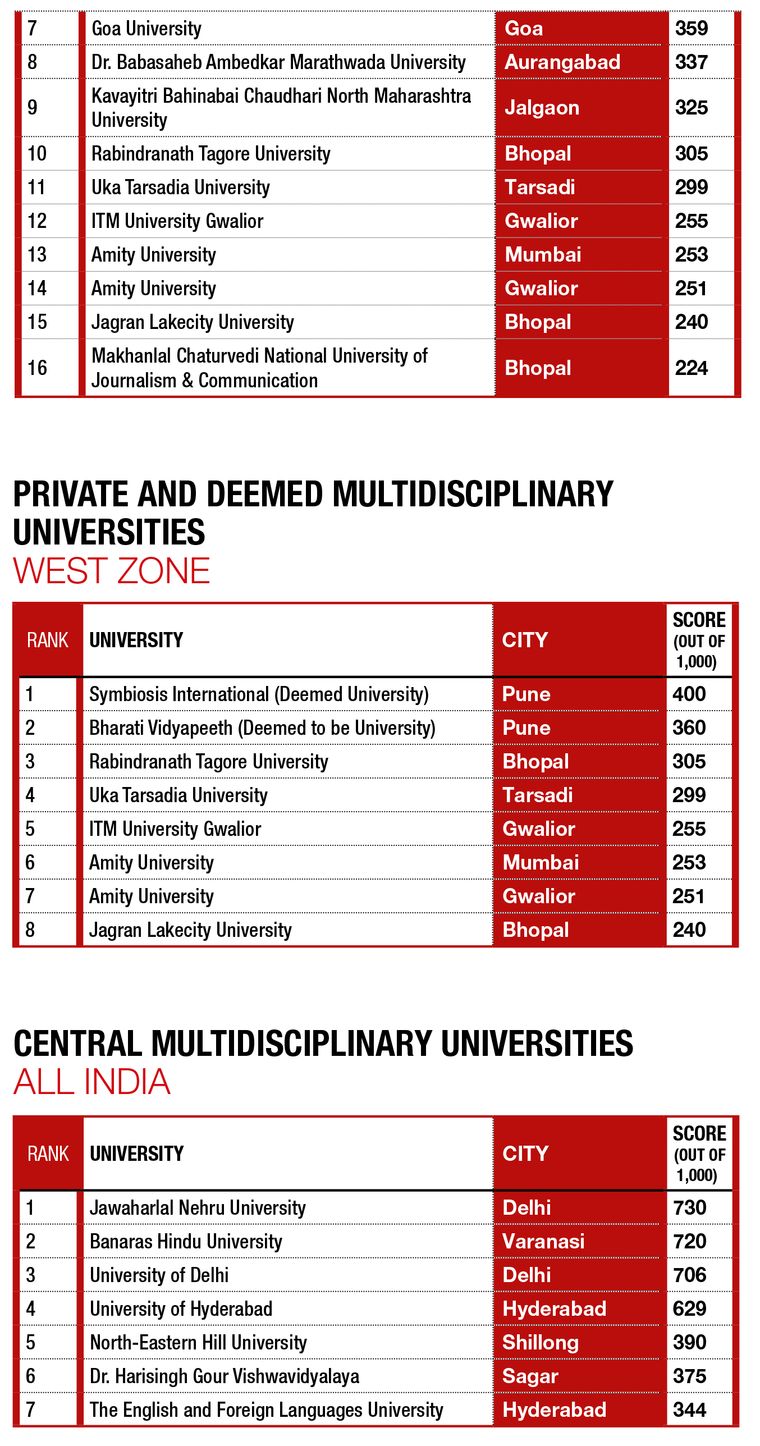

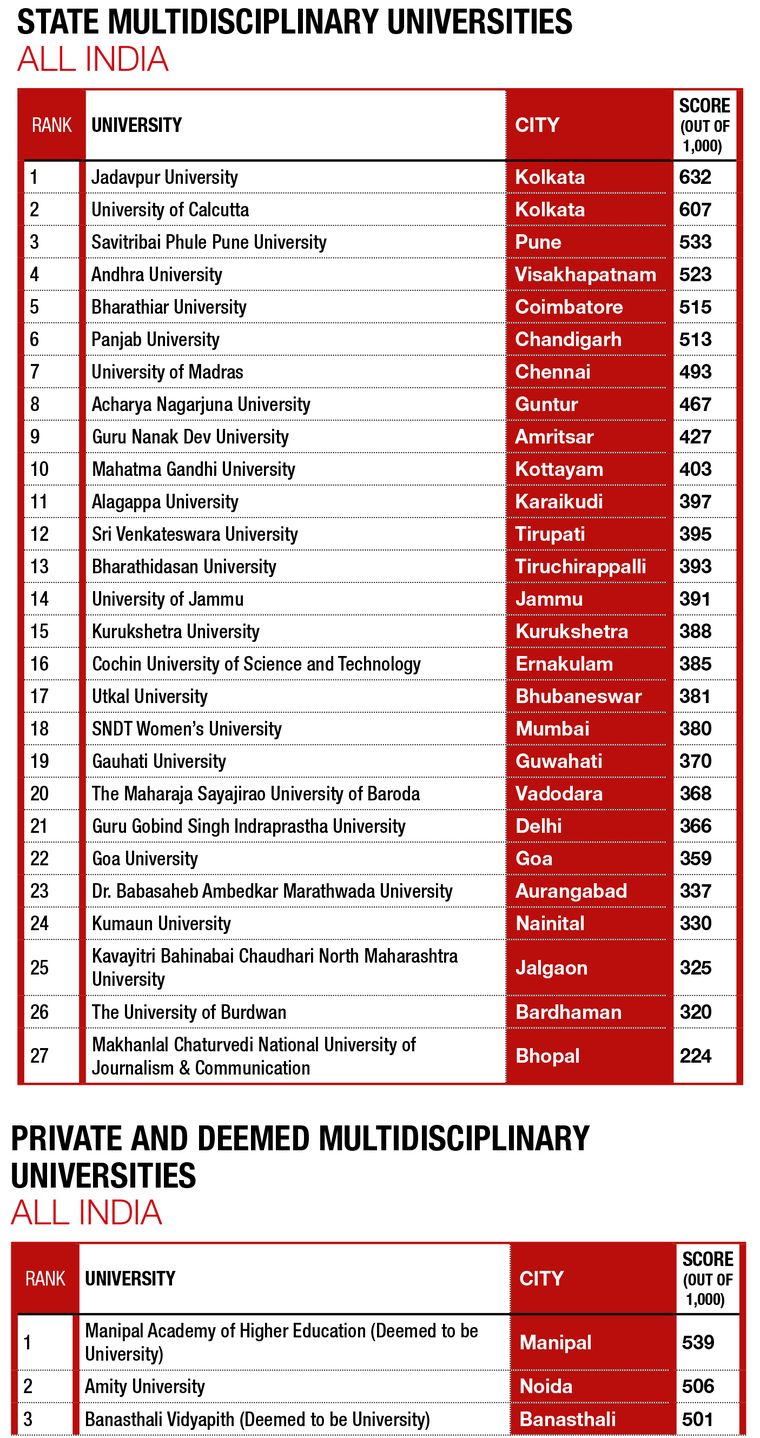

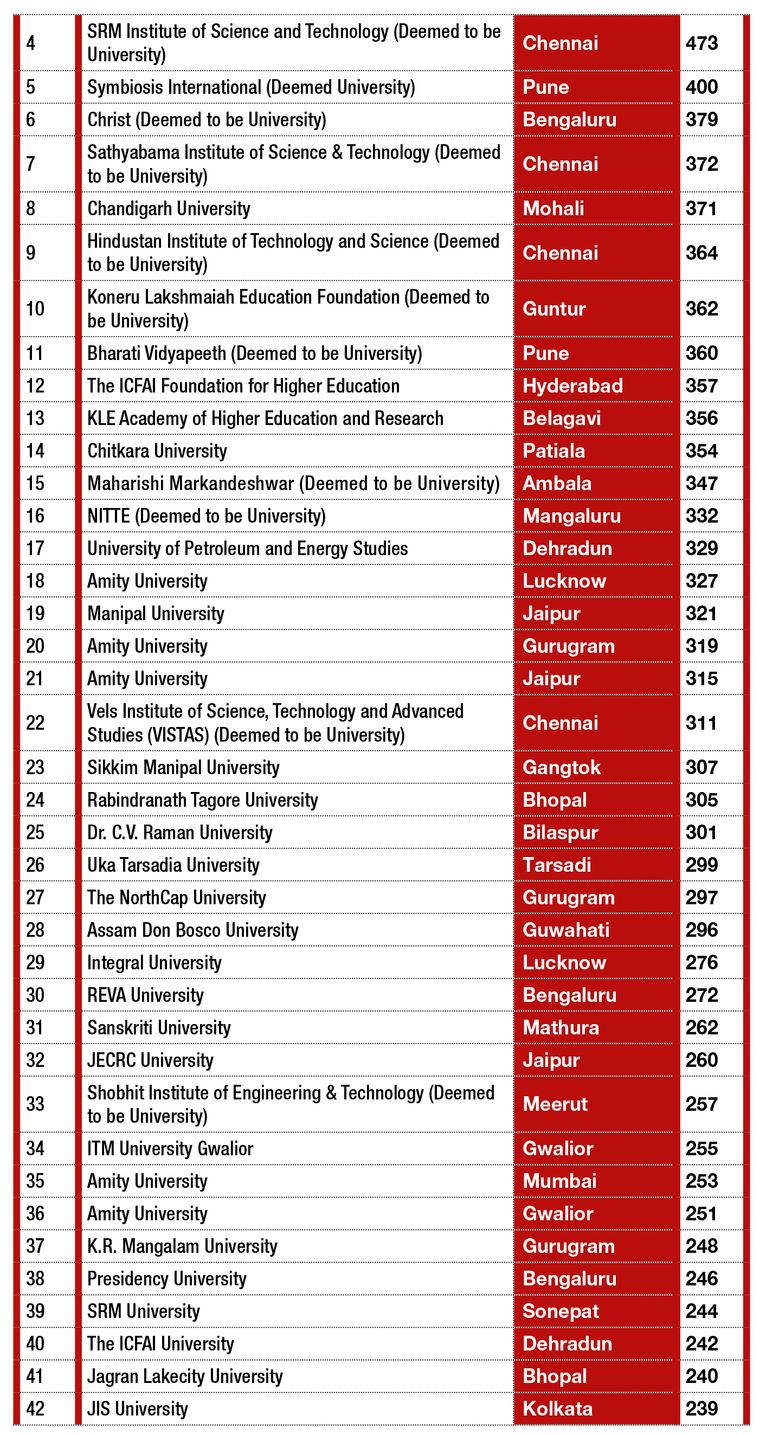

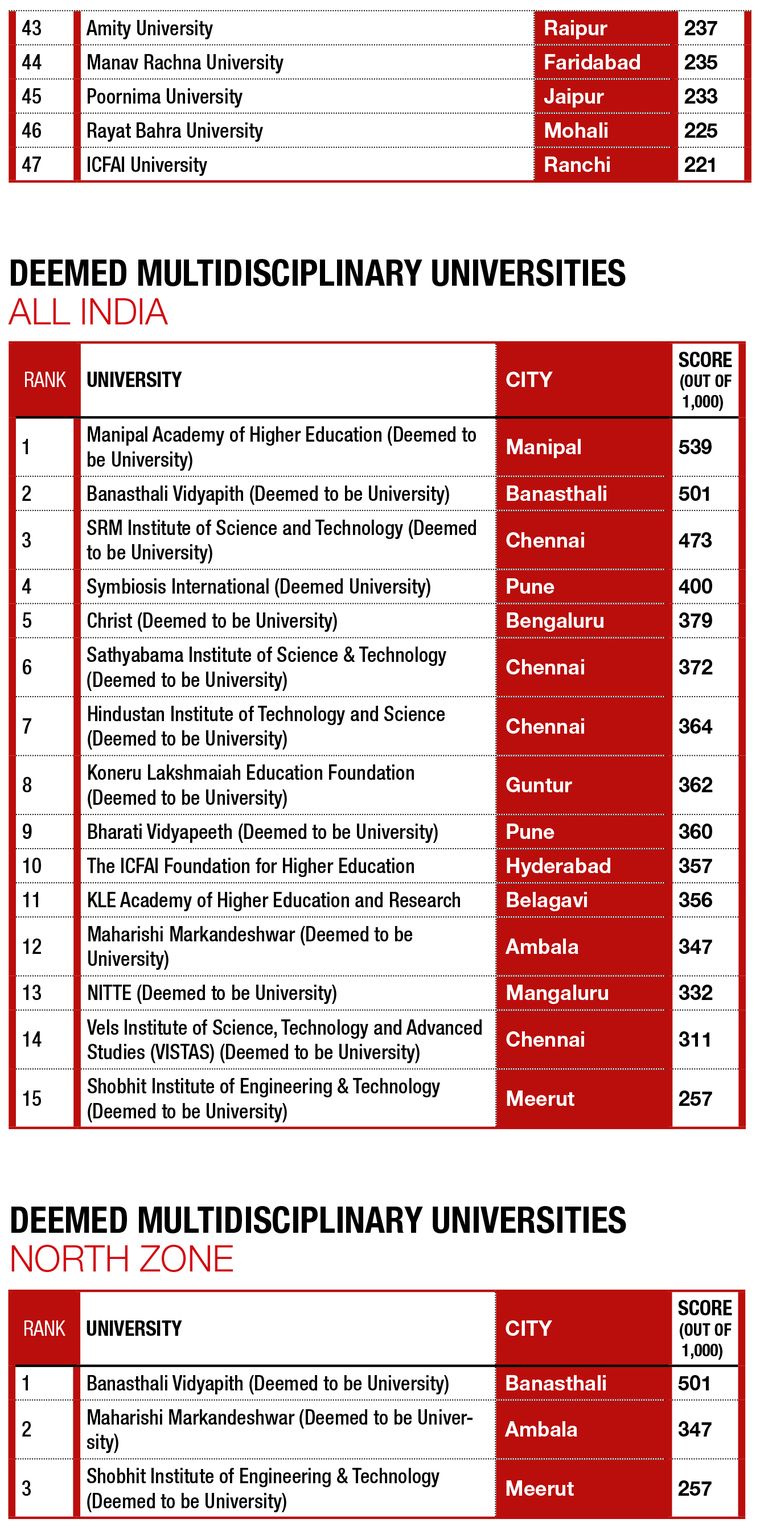

THE WEEK-Hansa Research Best Universities Survey 2022 provides insight into the hierarchy of multidisciplinary, technical and medical universities in the country. This year, the study was done across 15 cities.

To be eligible, universities had to be recognised by the UGC, offer full-time postgraduate degree courses in at least two disciplines and should have graduated at least three batches from the postgraduate programmes.

A primary survey was conducted with 340 academic experts, spread across selected cities. The respondents were asked to nominate and rank the top 20 universities in India.

Perceptual score was calculated based on the number of nominations and the actual ranks received.

For factual data collection, a dedicated website was created and the link was sent to universities. Sixty-two universities responded within the stipulated time.

Factual score was calculated based on information collected from universities and other secondary sources on the following parameters:

❖ Age and accreditation

❖ Infrastructure and other facilities

❖ Faculty, research and academics

❖ Student intake and exposure

❖ Placements (only for technical universities)

Final score = Perceptual score (out of 400) + factual score (out of 600)

Some top universities could not respond to the survey with factual information. For these universities, composite score was derived by combining the perceptual score for the university with an interpolated appropriate factual score based on their position in the list.