The sky is crayoned blue. The ground is squelchy like chocolate left out in summer. Rain has pelted nonstop for a week. And the sun filters through the freshly laundered leaves. At the Mahatma Gandhi Institute for Rural Industrialization campus in Wardha, the smell of turpentine—sprayed to ward off termites eating away Gandhian institutions—is eye-watering.

Across a bridge painted in tricolours, is the thatched house where Gandhi lived.

In Wardha where everything is Gandhi-touched, there is a little-known space of the other Gandhi—Kasturba. Ba ki Rasoi (Ba’s kitchen) is now turned into a shrine with an LED display of her husband. This is where his followers, those engaged in sangarsh for satya—the battle for truth—found sustenance.

It was no small task, catering for a revolution. Kasturba would be up at 4am. “She took part in all Ashram activities, besides—such as cleaning grain, cutting vegetables, making chapatis, etc.,’’ wrote Sushila Nayar, her doctor in an article on Ba and Bapu.

It is a large room. Faded photographs on the mud-plastered walls offer a glimpse of the sheer size of the operation it would have been. It was like feeding an army. She was as much a hard taskmaster as Gandhi, her organisational skills military efficient. “She demanded punctuality, scrupulous cleanliness, good manners and participation... from everyone eating in her kitchen,’’ wrote G. Ramchandran, who spent 1925 at Sevagram working with Ba in the kitchen.

This part—very much essential to the freedom struggle—has been taken for granted. But what has dropped off the mainstream memory is her being an active satyagrahi.

Those memories, if awakened, should be stirring even a century and a half after her birth. More so, in the 75th year of independence, when the freedom story is expanding to become more inclusive and has chosen to find the individual voice rather than the collective. Kastur, who was Gandhi’s comrade and companion, was a woman of strength who experimented with the power of truth.

She broke taboos by offering satyagraha in South Africa to protest a law that allowed only marriages performed under Christian rites to be registered. It nullified “…all marriages celebrated according to the Hindu, Musalman and Zoroastrian rites,’’ wrote Gandhi in the book Satyagraha in South Africa.

Kasturba wanted to resist the law. “‘Could I not then join the struggle and be imprisoned myself,’ she asked. Mr Gandhi said that she could but that it was not a small matter,’’ reported the Indian Opinion newspaper on October 1, 1913. It was a “tough” conversation in the teeth of discouragement by her husband, says their grandson, the historian Rajmohan Gandhi.

She was in the first batch of satyagrahis—12 men and four women—who travelled from Phoenix to Transvaal border on September 15, 1913. The women satyagrahis, besides her, were Kashi Chhaganlal Gandhi, Santok Mangal Gandhi and Jayakunwar Manilal Doctor. Their arrest created a sensation in India. In a public meeting, held in Bombay on December 10, 1913 to pass a resolution on the treatment of Indians in South Africa and to ask for an inquiry, one of the founders of the Indian National Congress, Pherozeshah Mehta, thundered: “While we are speaking and speechifying, those mild and gentle women who have enrolled themselves with husbands and brothers, under the banner of Passive Resistance, are lying in jails herded with common criminals.’’

They were sentenced to three months of hard labour. “The women’s bravery was beyond words. They were all kept in Maritzburg jail, where they were considerably harassed. Their food was of the worst quality and they were given laundry work as their task,’’ wrote Gandhi. Finally they emerged, “in many cases utterly broken down in the hard prison life…. Mrs Gandhi suffered most of all,’’ wrote C.F Andrews after their release.

Kasturba went to jail four times in India, each time in her own right. During the civil disobedience movement, when Gandhi was in jail, she chose to take his place. She addressed meetings and was arrested on January 11, 1933 and taken to Sabarmati Jail. She was sentenced to one and a half months of simple imprisonment. Her companions got three and a half months of rigorous imprisonment. She protested the preferential treatment and insisted on being treated the same. When she was released she plunged back into the movement and was jailed for six months.

In 1939, she was arrested for protesting the “reign of terror’’ that the ruler of Rajkot had unleashed on satyagrahis. And in 1942 during the Quit India movement, she was arrested as she left to address a meeting that Gandhi was to address. She never left the Aga Khan Palace alive.

She had stood in for Gandhi for the first time when he was in Yeravada Jail in Poona in 1924. She went to Borsad, responding to a telegram sent by women who had been lathi-charged. “We want Ba with us,’’ it read. She had not been keeping well, but as an eye-witness account suggests, it did little to dampen her spirits. “She was no more the meek woman who sat quietly in her hut… spinning the charkha.’’

She was 70 when she chose to go to prison, agitating against the ruler of Rajkot. It was a choice that Gandhi did not really encourage and he was not keeping well. But Ba, who had an emotional attachment to Rajkot, chose to become part of the movement. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel tried to stop her, but in vain. His own daughter, Maniben Patel, was arrested along with her.

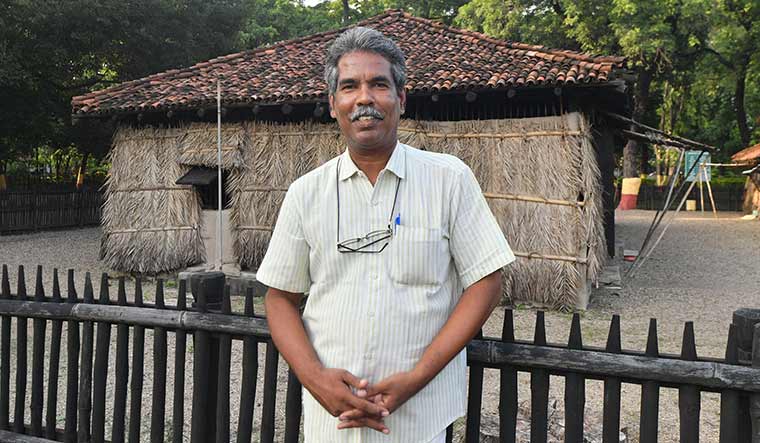

“Kasturba often played the role of an empowered and independent woman on her own,’’ says Siby K. Joseph, director of Jamnalal Bajaj Memorial Library and Research Centre, Sevagram, who has written a book, Kasturba Gandhi An Embodiment of Empowerment. “She came out on critical moments of national life displaying a rare kind of grit and determination. This was more when the Mahatma was away. But her life and her role in the struggle have remained largely unexplored.”

The Gandhi scholar was on a visit to South Africa and the Phoenix Settlement when he realised how “massive’’ her role was. “During this phase Gandhi was virtually absent. She managed it,’’ he says. He wrote the book in an attempt to ensure that she is given her due.

“My first view of Phoenix disappointed and depressed me,’’ wrote Millie Polak, one of the first western women followers of Gandhi. The Polaks had lived with the Gandhis in Johannesburg. It took them two days and nights in a train to reach Durban, from where the Settlement was 14 miles away. They reached the place after a “long two-mile tramp along a badly constructed road across difficult country, our paths lighted only by a flickering lamp, and the fear of snakes constantly in our mind.’’

If Kasturba had similar thoughts, they went unwritten. It is hard to fill in her silence. Gandhi made it his project to get his illiterate wife to read and write. It was a lifelong commitment. Even in her seventies, when she was imprisoned at the Aga Khan Palace, he tried to make her read the Gujarati primer. Kasturba did not leave behind her thoughts.

But HarperCollins India has published The Lost Diary of Kastur, My Ba, which has been translated from Gujarati by her great-grandson Tushar Gandhi. “We have all collectively neglected Ba and decided that she needs to be kept in the background,’’ says Tushar. “In translating the diary, I felt an intimate connection with Ba.’’

The diary was found at the Gandhi Research Foundation Jalgaon. From January to September 1933, the diary records common aspects of ashram life; prayers, reading the Gita and spinning. It captures the mundanity of life of running a revolution. The purity of soul that Gandhi demanded meant a complete transformation of self.

Tushar claims the diary is proof that Kasturba was not illiterate. To be fair to him, there has long been chatter of Ba keeping a diary. Sushila Nayar, her doctor, chronicled her memories of Ba in 1944, under the instructions of Gandhi who wanted her to be remembered. Sushila wrote about consulting diaries of Ba in this period. But these were largely believed to be dictated by Ba.

The only voice that exists is Gandhi’s. And that presents a fundamental problem of her relationship with Gandhi. Her dutifulness and her surrender, a word that is unpalatable in woke times.

“She has not been given her due,’’ says Urvashi Butalia, writer and feminist. “It is also the prism in which she has been framed [where she is seen only with Gandhi]. Women in the struggle were also wives who looked after their husbands. Men’s lives get represented. It is more important when, within the marginalised space, this is a marginalised voice. But it takes time.”

Kasturba was not the only one of her generation not to document her life. Kamala Nehru, who was highly literate, never wrote about her life. That Kasturba resisted Gandhi has been documented; her reluctance to embrace his mission against untouchability, for instance. She did not accept blindly.

She retains her own kitchen. Was that autonomy? “The question of autonomy is a misplaced question as far as Gandhi’s family is concerned,’’ says the scholar Tridip Surhud. “It would not have been a question if she was not his wife. In family, a lot of surrender and sacrifice take place, especially in the 19th century family. We forget that they were married in the 19th century.’’

There was silence, but there are memories. Stories that are now emerging. “I don’t remember hearing these stories when I was growing up,’’ says Sukanya Bharatram, her great-granddaughter. “I remember sitting with family members, even our extended family members, and talking about the freedom struggle as the past. I am grateful because it taught me to live in India in the present instead of living in the past that could have been limiting.”

Her mother, Tara Gandhi, is writing a book. She was 11 when Kasturba died. In an anecdote that reveals her grandmother’s character, Tara remembers the time she and her family went to visit the Gandhis at the Aga Khan Palace prison. “I asked her if I could play in the next room,’’ she says. “I said there were no guards. She said no. She was clear what wasn’t allowed, wasn’t allowed.”

Her brother Rajmohan Gandhi, a year and a half younger, too, has memories of her last days. “I remember the barbed wire around it and the soldiers guarding it,’’ he says. “It was called a palace, but it was a detention centre. I remember her being very affectionate. Just a constant flow of affection.’’ It was Ba who brought him into the world. And it was she who tended to his sister when she was very ill.

In Sevagram, Bapu still holds sway. It is different from his earlier experiments. He was 67 when he came here. Time is very much still. Sunlight filters through the trees. The prayers that Bapu started at 4am continue each day. As do the evening prayers. The kitchen, however, is not like how Ba had it.

Near the tulsi plant in Sevagram is Ba Kutir. Two bare rooms, the walls plastered in mud. No photographs allowed inside; the rule for Ba Kutir is strict. The hut was built as a concession to her advancing age—she was older than him. “There is very little of anything that belongs only to her,’’ says Kanakmal Gandhi, former director at the ashram. “Everything was jointly owned.’’

If Gandhi became Bapu, the father of the nation, Kastur was the universal Ba. It was Subhas Chandra Bose who, in a heartfelt tribute when she died in 1944, referred to her as the mother of the Indian people. “She became the mother of the nation before Bapuji became father of the nation,’’ says Tara. “But not in a formal way.”

But more than the “mother of the Indian people’’, Ba was the spirit of the fight. “It was Ba that women came to pour their hearts out to,’’ says Vibha Gupta, chairperson, Magan Sangrahalaya, Wardha. “She was like the thread in a string of beads. It is invisible but it keeps the beads together.’’

Ba helped in spreading Gandhi’s message; in making it accessible and relatable for those who did not necessarily understand his philosophy. It is her that turns the saint, human. She keeps the family together; she helps with the delivery of Rajmohan; she finds a way to restore Devdas Gandhi to his health when he has a breakdown. And it is she who insists that Gandhi free Sushila Nayar, who was with them in the Aga Khan Palace, from her self-imposed vow of not writing letters home to her mother. Gandhi had taken a decision not to write letters as he was not allowed to write political letters. Sushila’s brother Pyarelal, who was Gandhi’s secretary, also takes the vow. Ba, however, understands that the mother would worry. She includes the stories of Sushila in her letters to Devdas so that he can pass the message on.

She had the same concern for her daughters-in-law. “Ba changed the order in the kitchen when my mother went to visit in Sabarmati,’’ says Tara. “She said, ‘I know there is a rule here that you don’t put rice in the evening. But my daughter Lakshmi has to have rice.’” Lakshmi, daughter of C. Rajagopalachari, was from rice-loving Tamil Nadu.

In her book Kasturba, Sushila narrates her first meeting with Ba in 1920. Her mother was unhappy about Pyarelal joining the freedom movement. She asked to meet Gandhi. “She was going to him to request him to send her son back to her,’’ Sushila writes. She was to meet him in Lahore. “But when she reached there, she found both of them too busy to see her, so she spent the day talking with Ba and unburdening herself. Ba was all sympathy and in return narrated her own experiences and the hardships that she had passed through whilst following in her husband’s footsteps in the service of the country. By the time Gandhiji sent for my mother in the evening, she was a different person. She had been deeply impressed by what Ba had told her. She had argued with herself that after all Ba, too, was a mother like herself. If Ba could sacrifice so much, why could not she? So she said, ‘Gandhiji, you can keep my son for four or five years at the most, but send him back to me after that. I have lost my husband and he is the only light of my house…’ My mother had simply fallen in love with her. Gandhiji had twitted her for clothing herself and even her little child (me) in foreign clothes. He had also spoken to her about the vanity of attachment to the world. All that was perfectly true, but although it served to silence my mother it left her sighing. The air was too rarefied for her to breathe. With Ba it was different. She spoke to her from her own level—as one woman to another.’’

In a way Kasturba helped transform him. As Gandhi told the Pashtuns in 1938, “She became my teacher in nonviolence.”

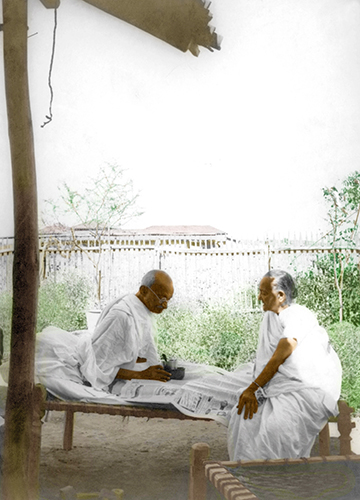

But at the heart of the Kasturba story lies the legacy of Gandhi. While it is essential that her role as a freedom fighter be recognised, theirs is also the story of togetherness. And of a marriage of respect and love. Bapu and Ba were exceptional as they were the only couple involved in the freedom struggle in public life. There was no other. “They had an equal relationship,’’ says Tara. “She never did anything obediently. She argued, she accepted if she wanted to. She never said forgive me.”

Like in life, even in afterlife, Gandhi continues to dominate the landscape. But his dutiful wife—his nurse, his faithful companion, his comrade, his partner and his teacher, Mrs Gandhi, as he referred to her in many letters—was always beside him. He was conscious of her influence. Besides making Sushila put down her memories of Kasturba, he founded the Kasturba Memorial Trust to carry on her work in the villages. “Give me an example of a man who spun enough yarn for two saris,’’ says Suhrud. “He wove her saris. One, she was cremated in. The only other survives at Sabarmati Ashram. If that is not love, what is?’’

Seventy-five years after freedom, it is time perhaps to expand the frame to include her more. And acknowledge the relationship of the only public political couple that battled together for freedom.