When it rains, it pours in queries. Will schools go online? Will flights be delayed or cancelled? Will it affect crops? Should I carry an umbrella to office? Will the cricket match be called off? Braving a volley of questions is a growing community of independent weathermen in India that has been capturing cloud images and tracking rainfall, temperature and wind direction to accurately predict weather and weather events like thunderstorms or floods. The technology upgrade in weather forecasting has been a boon for aspiring weather bloggers as they now get real-time data―satellite images, maps, charts and weather models―on their mobile phones. Their timely updates and predictions are not only making the common man weather-wise, but also helping avert loss of life and property. And, in the age of the internet, they have acquired celebrity status, especially post the 2015 Chennai floods.

These weather enthusiasts come from diverse backgrounds, bound together by a passion for all things meteorological. Take, for instance, Rajesh Kapadia, 69, a retired businessman from Mumbai. He runs the Vagaries of the Weather blog. Then there is Sai Praneeth Burra (@APWeatherman96), 25, an electrical engineering graduate. His forecasts benefiting the villages in Andhra Pradesh even found a mention on Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Mann Ki Baat. In Kolkata, Santosh Subramanian, 28, relies not just on real-time data but also on real-time reporting from a huge community of citizen reporters to update his Weather of Kolkata blog. Pradeep John, 40, better known as Tamil Nadu Weatherman, is the go-to man for people of Chennai, a city that witnesses relentless rains for eight months a year.

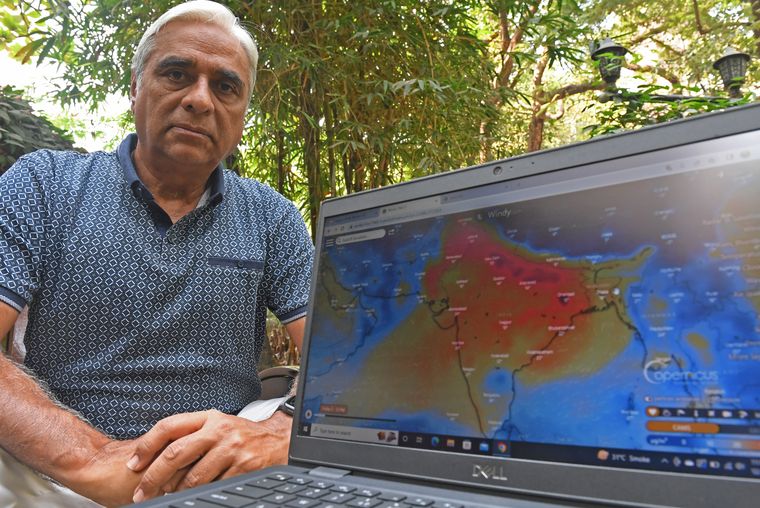

Kapadia, a self-taught meteorologist, started his blog (www.vagaries.in) in 2008. Today, it ranks second in India and 33rd in the world on Feedspot’s 100 Best Weather Blogs and Websites. “Ashok Patel, the first weather blogger of India (gujaratweather.com), and AccuWeather (an American weather forecasting company) helped me organise the blog,” recalls Kapadia. “Every day, I check if there is any big system coming in that is likely to disturb the atmosphere and livelihood of people. Systems are graded as low pressure, depression, deep depression and cyclone, and a closer examination of the weather data and weather models helps one predict accurately and perhaps give early warning.”

As a child, Kapadia was drawn to rains and clouds and would flip through newspapers to read the weather forecast. “I used to visit the regional meteorological centre in Colaba,” he says. “The observatories had to record the readings manually. In the 1980s, the centre started accessing satellite images once a day around 4.30pm. Now we have automatic weather stations in every state. The weather chart and the satellite images are accessible on your mobile phones. The Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) continues to rely on manual stations to officially record the parameters as per the norms set by the World Meteorological Organization.”

If it was the movement of clouds that intrigued Kapadia, John was wonderstruck by the 1994 cyclonic storm. “During the cyclone, I heard a howling sound and got intrigued,” says John, whose Facebook page ‘Tamil Nadu Weatherman’ saw an uptick in followers following his updates during the 2015 Chennai floods. “Again in 1996, heavy rains that lashed the city resulted in a two-week holiday for schools. I later learnt that it had rained nonstop for 36 hours.” There was no power, and all he could watch was the rising water level. “I grew fond of the rains and I never get bored watching it,” he recalls.

In 2016, John’s popularity soared further following his predictions on Cyclone Vardah. From a few likes in 2010, his page today has more than 800k followers. “In 2014, my FB page had very few likes but after 18 months, following the 2015 Chennai floods, people started watching my updates keenly,” says John, senior manager, Tamil Nadu Urban Infrastructure Financial Services Limited. “The blogging community chipped in and gave instant updates, gave tips on how to interpret radar data. Weather is being taken seriously now even by the common man.”

That is not surprising for a city that boasts the highest number of weather bloggers. And, that includes one of the country’s oldest weather blogs―KEA Weather started by K. Ehsan Ahmed in 2004. KEA Weather is also the first in India to have an automatic weather station to track live weather. In 2005-06, the KEA Weather blogging community started growing as the city faced both severe drought and floods. The community has now percolated to the micro-level, with locality-wise groups operating and giving instant updates.

“Many people in Chennai are interested in weather as the city has eight months of rainfall from June to January and the period between February and May is dry,” says John. “The temperature soars in May and is locally known as kathiri veyil (scorching sun). As it is eventful all through the year, people here have become aware and are weather-wise.”

Citizens of Kolkata, too, keep a keen eye on weather events. It has helped Subramanian immensely with his Weather of Kolkata blog. He now works with a group of six people, who are based in Kolkata, Hyderabad and the United Arab Emirates, and his weather community has around 500 citizens sharing data and live visuals from across West Bengal during any events.

“It has been a decade since we started doing hourly updates for West Bengal and eastern India,” says Subramanian, who started his blog in 2011. “We average out the data from IMD and international weather models to arrive at an accurate forecast. Readings come in only by 8.30am, and it takes another two to three hours to analyse them and then we send the daily update on social media. The second half of the day is dedicated to tracking possible weather events over the next week or later.”

A graduate in computer hardware and networking, Subramanian strives to devote more time to his passion during weather events amid his hectic professional commitments of running an event management and photography company. Cyclone Amphan that razed through West Bengal, Odisha and Bangladesh in May 2020 pushed the team to step up and work from remote locations. Subramanian is now reading through the city’s data on rainfall and the minimum and maximum temperature recorded between 1880 and 2010. “There is a distinct pattern,” he says. “In 1978, Kolkata witnessed the flood of the century. I feel we are overdue for such an event in this decade. The 2007 flood was devastating but it was on a lesser scale. The truth is still hidden in the data.”

Kolkata’s weather is distinct, says Subramanian, owing to its proximity to the ocean and its pollution woes as it lies in the same fog belt as Delhi. “We enjoy three distinct seasons unlike many other cities that might have a lengthy monsoon and a shorter winter,” he says. “Over the last three decades, I have noticed a pattern where the onset and withdrawal of monsoon is getting delayed. This has a huge impact on agriculture and people. Prior to 2010, the ‘Kalbaisakhi’ (Nor’wester/summer storm) used to arrive in Kolkata between 3pm and 5pm. But now it does not reach Kolkata before 6pm. There has been an extreme change in weather. This Durga Puja, we had 90mm rainfall in just 40 minutes, which is unprecedented.”

The updates and predictions by these independent weathermen are helping not just farmers and common people but industries, too. “This year, steel industries and tea estates sought specific forecast to tweak their work cycles to minimise losses and to better prepare for eventualities,” says Subramanian. “A tea estate company told me that they could save 15-20 per cent of losses if I could provide them forecast with 80 per cent accuracy. Often, the IMD forecasts might not reach them on time, or the format might not be user-specific or user-friendly. We alert the farmers in northeast India, too, as they also get Nor’westers. If we alert them three to four hours in advance, they can take effective steps to protect their harvest. Many farmers in West Bengal who feared the winter rains messaged us directly before sowing the seeds, as hailstorm destroys new saplings.”

For farmers and villagers, Burra from Tirupati started posting weather updates on Facebook and YouTube, and on Instagram for the urban crowd. “The prime minister mentioned my efforts during his Mann Ki Baat show in July 2021 as I was trying to help local farmers dealing with uncertainty owing to lack of timely weather updates,” says Burra, who is senior engineer with Bosch in Bengaluru.

When Burra started his weather blogging journey in 2012, there was limited data available. He had to pay to subscribe to agencies for weather information. The weather models, too, were not accurate till the technology evolved in 2014. His day starts at 5.30am when he goes through the radar data from IMD and satellite data from international agencies.

“As most people go through weather updates by 7am, before they head for work, I need to post the updates early,” says Burra, who frequently attends workshops at the National Atmospheric Research Laboratory in Andhra Pradesh to keep abreast of latest weather technologies. “After collecting data from multiple sources, I analyse it based on past patterns. The monsoon season is the most hectic in Andhra for weathermen as it rains in the morning and people expect an early forecast. I have simplified the process to save time by preparing a code to read different data together during analysis. I copy the final data (update) to social media.”

No matter how many hours they spend poring over data, predictions do go wrong at times. “Sometimes, we are trolled for inaccurate predictions,” says Burra. “But it is part of the game. Mistakes prod us to learn.” But the trolling that independent weathermen get is nothing compared with the ridicule the IMD is subjected to online.

Independent weathermen are much sought after as they are direct and precise, and communicate fast and in a simple language, unlike the IMD, whose cryptic messages and jargon cannot be decoded by the common man. But the IMD has a lot on its plate, say independent weathermen, and cannot cater to every corner like localised bloggers can. IMD forecasts are meant to assist weather-sensitive activities like agriculture, irrigation, shipping, aviation and offshore oil explorations or give warning against severe weather phenomena like tropical cyclones, Nor’westers, dust storms, heavy rains and snow, cold and heat waves that cause destruction of life and property. Even though the IMD is bolstering its observational network by adding more radars, automatic weather stations, rain gauges and satellites to improve predictability, mistakes are bound to creep in.

“I am a meteorologist and not a magician,” says Kapadia. “Nobody can predict weather accurately as it is nature and changes happen constantly. If the pressure drops, you know the night is going to be stormy. Wind direction at various levels, pressure at the surface level and temperature are factors that need to be looked at. If the sea is warm, the brew is stronger. But as the conditions keep changing, predictions might not be accurate.”

Also, the timing plays an important role. “The weather models give different indications depending on the time of the reading,” says John. “Two weeks prior to the event, the accuracy is only about 50 to 60 per cent. Nearing the event, the model accuracy is better. Bloggers can afford to forecast rains with certainty while the IMD can say it is only a probability owing to its format of releasing data for consumption by various departments or sectors from aviation to agriculture. We, too, cannot give town-wise predictions as the grid size in the weather models is 11-27sqkm and weather situation varies drastically over time and space. Each member in the global model ensemble gives out data and if 50 per cent of members have predicted rains, the prediction might have better accuracy. Sometimes, none can predict accurately.”

The way forward is to simplify forecast and ensure better outreach, says Burra. “The accuracy is improving as India now has better weather models and a supercomputer at Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, Pune,” he says. “Wind is the basic parameter for weather forecast. We need to see if it is dry or wet wind. Temperature is another parameter as a cyclonic system causes rain and an anti-cyclonic system will lead to a dip or rise in temperature, depending on the season. The precipitation chart alone does not assist in forecasting as wind analysis and the knowledge of past events and patterns help in achieving accuracy.”

The art of weather forecasting is like the clouds that quietly brew a storm or a rainfall. Only a careful reading of data and intuitively drawing inferences from past patterns make for accuracy. Not many would guess that it is actually the type and pattern of the clouds in the sky that determine if it is going to rain. It takes an intriguing mind to observe why cyclones rarely strike during the monsoon months or that the warmer oceans brew stronger cyclones. The weathermen of India who are on a roll seem to have some answers and a multitude of questions.