Sayajirao Gaekwad III was a huge source of support to a young B.R. Ambedkar. The ruler of Baroda (now in Gujarat) provided him scholarships and employment. It would not be wrong to say that Ambedkar went on to become an institution. Sayajirao also made a telling contribution to another great Indian institution. In 1927, he donated Rs2 lakh towards the establishment of the Central Library at the Banaras Hindu University.

The university librarian Dewendra Kumar Singh proudly tells THE WEEK that they have priceless manuscripts, some of which are written in gold. “In the last couple of years, our library has grown phenomenally,” he says. “We have around 16 lakh printed documents, 86,000 e-books, and around 1.5 lakh video lectures, plus 10,000 journals. All our publications can be accessed remotely.” The library has around 5,000 daily users and is open almost round-the-clock―it is closed only for cleaning, which takes three hours. Even during those hours, students continue to queue up outside, sometimes numbering around 500, as per Singh.

“Research and citations are the strength of BHU, and a few science departments such as life sciences and medical sciences are among the top ones,” says Dr Vijay Kumar Shukla, rector, BHU. “With the IoE (institute of eminence status and the associated government grant), we have been trying to encourage our young faculty and other faculty members to go ahead with their publications. Under the IoE, we have appointed 15 to 20 post doc fellows. They are now in a position to produce good publications.”

BHU is the largest residential university in Asia, housing around 20,000 students in-campus and another 20,000 close by. But, like other top Indian universities, it is not ranked among the best in the world. For example, in the QS World University Rankings 2023―one of the world’s most-consulted such lists―there are no Indian universities in the top 100. A reason for this is that apart from criterion like academic and employer reputation, research and faculty-student ratio, the ranking also focuses on diversity―international student and faculty ratio. This puts Indian universities at a disadvantage because aspirational migration is usually higher to western countries. For instance, Rice University, Houston, Texas, which is ranked 100th in the QS list, scores 90 out of 100 for international faculty ratio and 92.6 for international student ratio. BHU scores 1.3 and 1.9, respectively.

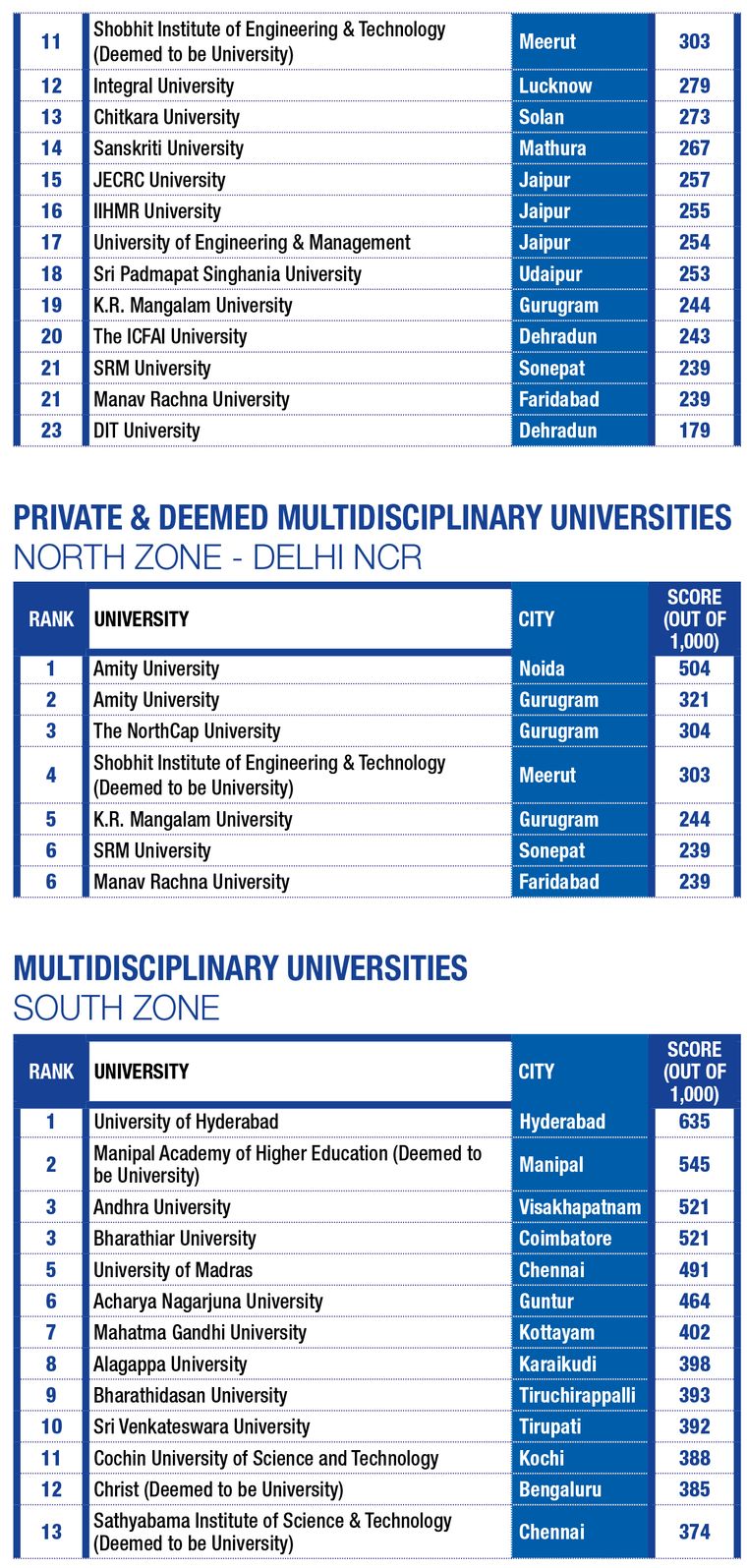

But, BHU, which is ranked second among multidisciplinary universities in India by THE WEEK-Hansa Research Survey 2023, is determined to bridge the diversity gap. It has earmarked posts for foreign faculty and has set up accommodation. It is also attempting to attract foreign students and is ready with hostels for them. Moreover, it has separated foreign student admissions from the Common University Entrance Test as they want confirmation by March.

“Teaching is never done in a closed environment,” Prof Arun Kumar Singh, registrar, BHU tells THE WEEK. “People should come from different countries and our people should go to different countries. Most of our students are from Uttar Pradesh, Bengal, Bihar and surrounding areas. When they get exposed to the teachers coming in from different parts of the world, it will help them widen their horizons.”

Prof A.K. Tripathi, director, Institute of Science, BHU, says excellence and ranking are different things and adds that the university has a few institutes par excellence such as the institutes of medicine, agriculture, environment and sustainable development. He also points out that BHU is one of the Indian government’s Sophisticated Analytical Technical Help Institutes, along with IIT Delhi and IIT Kharagpur. SATHIs have the facilities and analytical instruments to help industry, other universities and national laboratories. “Samples that were send abroad are sent here now,” says Tripathi.

For the University of Delhi (DU), which is third among multidisciplinary universities in THE WEEK-Hansa Research survey, the size and challenges are vastly different from foreign universities, says Prof Yogesh Singh, vice chancellor. “Many teachers were working on an ad hoc basis for several years, but now we are hiring more teachers,” he says. “We are conducting interviews 20 days a month and, in the last eight to nine months, we have recruited more than 500 teachers. At the same time, we are focusing on funding research and recruiting people with the right kind of research potential.”

He adds that the university’s international department is taking a keen interest in admitting international students. “We do not have international faculty on a regular basis,” he says. “Currently, we have around 20 adjunct international faculty members who have been engaged from different countries. Those who have an idea of the international system know that DU is a good university, but there may be professors who do not have any idea about India or Indian universities. The government of India recently allowed having international faculty. [With] the government taking the right steps, the image of India has improved in the last few years. I am hopeful that in the next few years, universities from India will be among the world’s top universities and DU will be one of them.”

Singh points out that there has been a huge response to the undergraduate courses in Delhi and many students are not able to get admissions for them. “But many students from India still prefer to go abroad for higher education, especially in the US and the UK,” he admits, adding that the perception would change over the next few years.

Singh is of the opinion that if foreign universities set up their campuses in India (the University Grants Commission is moving in this direction), it would be good for the country as students will have different kind of opportunities. “[Indian campuses of] foreign universities may not be affordable to all, but they will create different types of opportunities for our students in emerging areas of knowledge,” he says.

IIT Bombay, ranked first among technical universities in THE WEEK’s survey, is on the right path, says its director, Prof Subhasis Chaudhuri. “One needs to understand the journey to the top for IITs,” he tells THE WEEK. “The first 20 to 25 years since inception―that I call IIT 1.0―IITs had to concentrate on creating extraordinarily trained manpower, which they have been doing very well ever since. Subsequently, the need was felt to also emphasise on research-based postgraduate education. This is what I call IIT 2.0. For the last five to 10 years, we are also focusing on industry interaction for greater economic and societal impact. I would say all these would slowly make IIT Bombay truly world-class.”

He also points out an issue with the definition of “foreign” faculty. “In most western countries and ranking organisations, they look at the citizenship at birth, while majority of them had done their PhD in the same country,” he says. “This may be taken as ethnic diversity, but there is no academic diversity. On the other hand, IITs have tremendous academic diversity where a large number of faculty members have their PhDs from all over the world, but very few with non-Indian ethnicity. Most of the faculty members, thus, do have significant international exposure. Further, IITs, being centrally funded technical institutes, have excellent cultural diversity. In my opinion, academic diversity is more important than the passport of faculty.”

Chaudhuri says that as India is a large country with a highly aspirational youth, foreign universities setting up their centres in India would be a welcome move. “I shall be happy to be of help in such initiatives and I am sure all IITs will be happy to collaborate with them, should there be such opportunities,” he says. “However, we need to be careful in ensuring that there is no compromise in the quality of education that these foreign universities deliver in India.”

IIT Bombay, which produces the largest number of PhDs in STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) in India (449 PhDs last year), has been working towards an ecosystem that fosters cutting-edge research and innovation. With the Centre’s IoE grant, it has been setting up world-class laboratories to ensure that researchers have access to high-end tools and facilities. Several interdisciplinary centres and various centres of excellence have been set up. These include the Koita Centre for Digital Health, the Centre for Machine Intelligence and Data Science, and the Centre for Climate Studies.

The entrepreneurship ecosystem, which has incubated companies with a combined valuation of more than $2.5 billion, is set to get stronger―a new research building, which will house startups, will be ready in six to eight months. IIT Bombay is also setting up a translational research centre that will take early concepts in academic departments to maturity and “productisation” stages. Curriculum updation is, of course, continuous, in keeping with global technological developments. “Once in 10 to 12 years, we do a major overhaul and the last major change in UG education happened in 2021,” says Chaudhuri.

Prof Rangan Banerjee, director, IIT Delhi, ranked second among technical institutes by THE WEEK, feels that academic institutes, particularly IITs, have a role towards society as they are training future manpower and not just competing for international world university rankings. “We have many things to do to increase the impact of our education and research,” he says. “We would not do it with the goal of improving our ranking. We have to provide an all-round education for our students and also see what is needed, in terms of whether it is societal organisations, government or the industry. In such cases, we need to be aware of what is happening across the world. Our focus would be to do things that will enhance the student experience, see that we are doing research on relevant problems, see that the knowledge that we generate actually makes an impact on society and provides leadership of thought.” He adds that doing these things would automatically improve IIT Delhi’s global ranking.

Banerjee says that IIT Delhi attracts a diverse group of students from across the country and that its students are doing well and making an impact, but adds that the impact now needs to be enhanced. “There are certain areas where we need to get the groups of faculty members together and make a greater impact,” he says. “In health care, we are planning a new campus in Jhajjar, Haryana. We are working with AIIMS Delhi and the National Cancer Institute. We are looking at personalised medicine and new areas of sports-injury prevention and sports performance.” He adds that IIT Delhi also has a school of artificial intelligence funded by alumnus. “We are going to get a separate high-performance cluster which is going to be for AI,” he says. “It will be a national facility predominantly for AI. It will also be open for researchers from across India.” Banerjee says the government has asked the institute to have an international presence and, consequently, IIT Delhi is going to have an Abu Dhabi campus soon.

He says having foreign faculty can surely help and adds that IIT Delhi has temporary faculty from Japan and Germany. “We even have Nobel laureates visiting us,” he says. “The whole idea is that we have different ways of looking at things and we do joint workshops and research projects with different universities. We will prioritise a set of universities, but we are insisting on two-way traffic in linkages. Under this, students can go and come.”

Banerjee emphasises the need to keep reinventing. “It is an interesting and exciting time,” he says. “One of the challenges for higher education is that students now have lots of choices and can google in the classroom. It is challenging to actually get their attention. The approach cannot be conventional.” For this reason, he says, IIT Delhi has an innovation ecosystem where students and faculty can run with their ideas. “We would like many of our students to become job creators rather than just go and sit for placements,” he says.

Prof Sajal Dasgupta, vice chancellor, University of Engineering & Management, Kolkata

Having foreign faculty and/or Indian faculty with substantial international experience is important to bring in foreign and global perspectives in the area of study. This also helps promote inclusiveness in education and explore more dimensions of the subject.

Kadhambari S. Viswanathan, assistant vice president, Vellore Institute of Technology

Future-ready programmes ensure that students become capable of strengthening and influencing the future of work. Such programmes in a student-centric learning environment―with technology-enabled peer learning through interactive strategies― will help train students with competencies desirable today.

Prof Devinder Narain, senior director, corporate relations & human resource, Shobhit University

A combination of factors contribute to making a university stand out. This includes a strong academic reputation, excellence in research and innovation, having an impact on society, valuing diversity and inclusion, and strong alumni network that can offer students valuable connections.

Prof P.R. Sodani, president, IIHMR University, Jaipur

Universities have to be committed to harnessing the new opportunities emerging in our dynamic, fast-changing world through interdisciplinary research, innovations in pedagogy, providing world-class infrastructure, and facilitating entrepreneurship. Current research by faculty should be integrated with teaching, leading to industry-ready students.

Sardar Simarpreet Singh, director, JIS Group

Universities must produce society-makers who are capable of providing leadership to their fellows and juniors. They can innovate the essential things for the society of the future and add value to the rapidly changing world. Also, the internation-alisation of education is a growing urge of the universe and is gaining momentum.

Research methodology

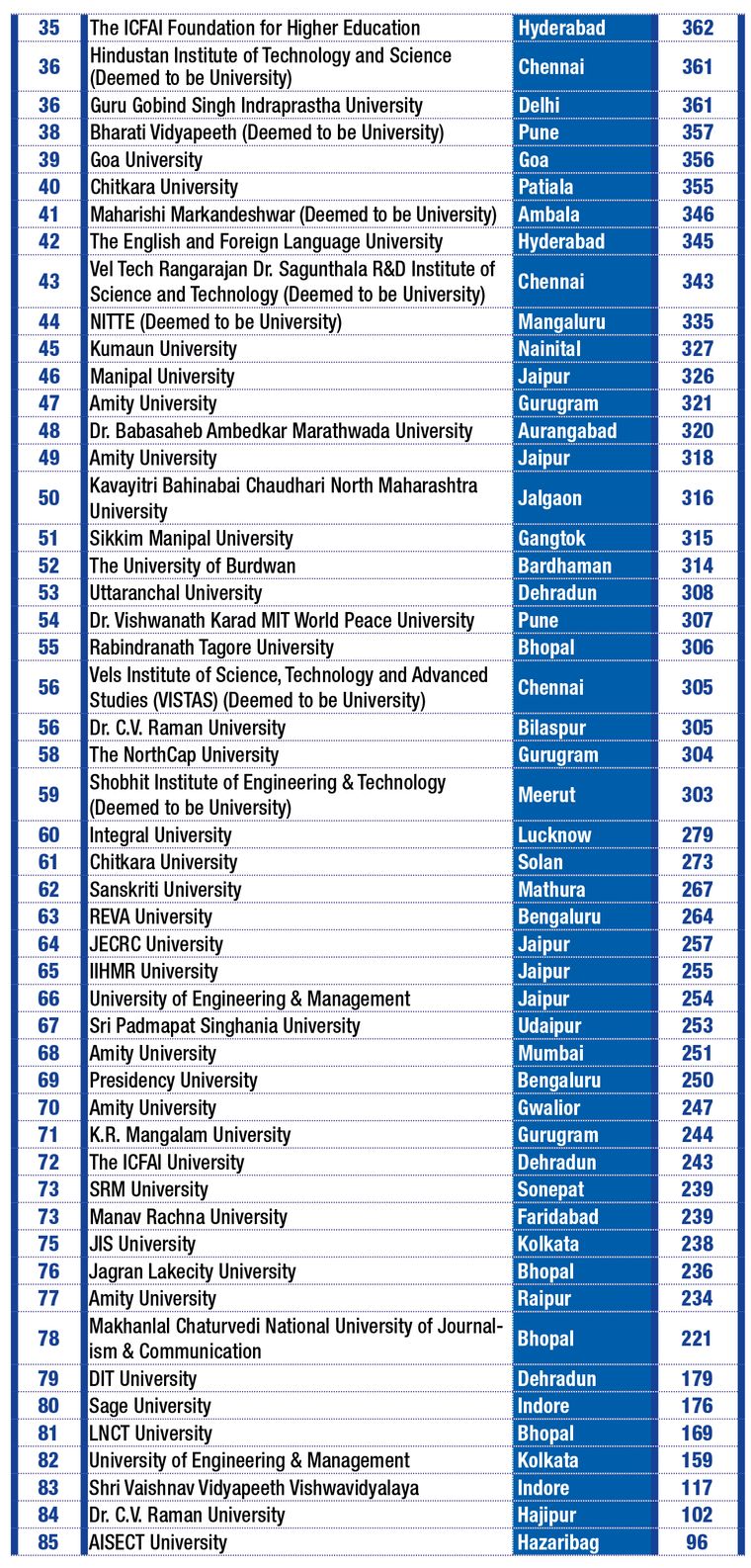

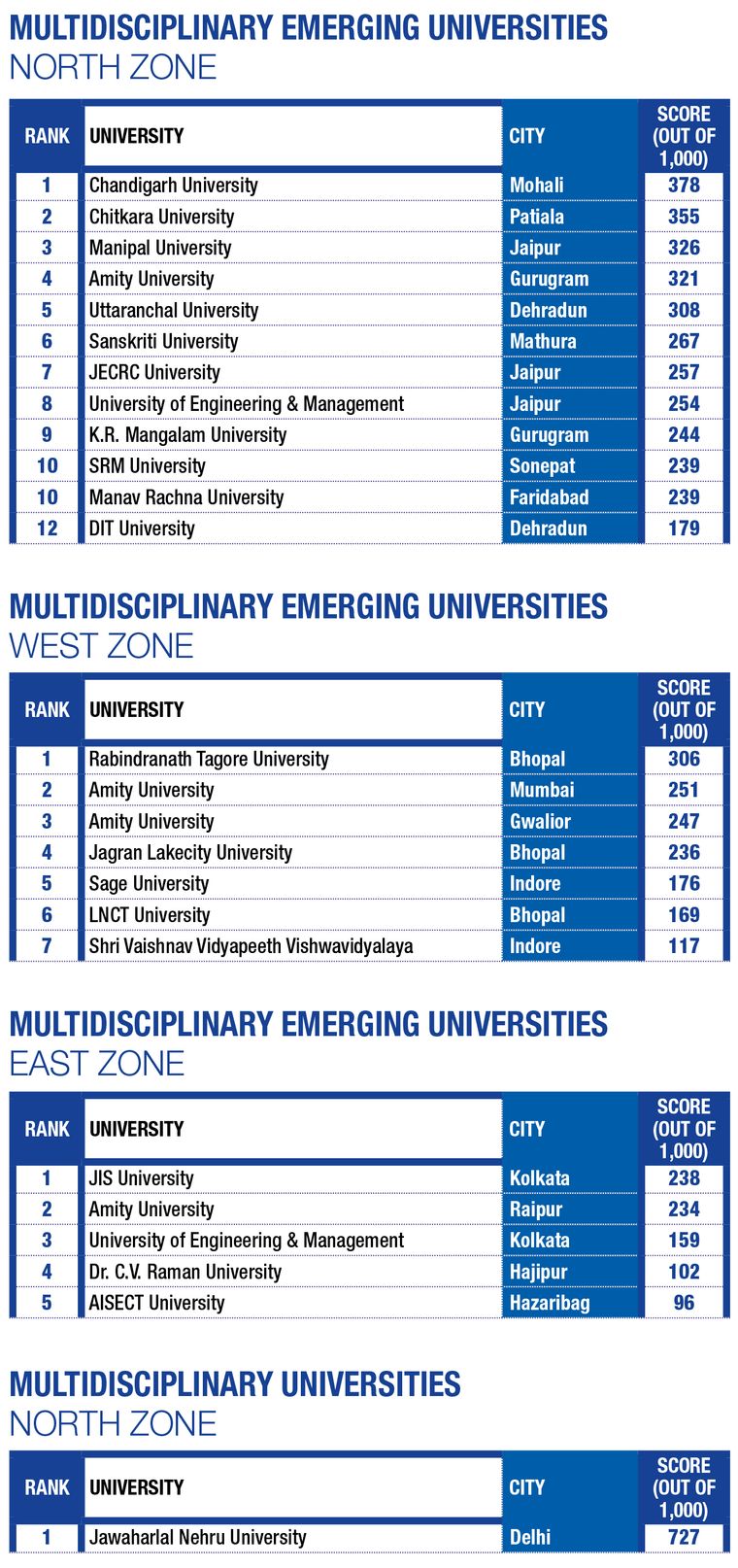

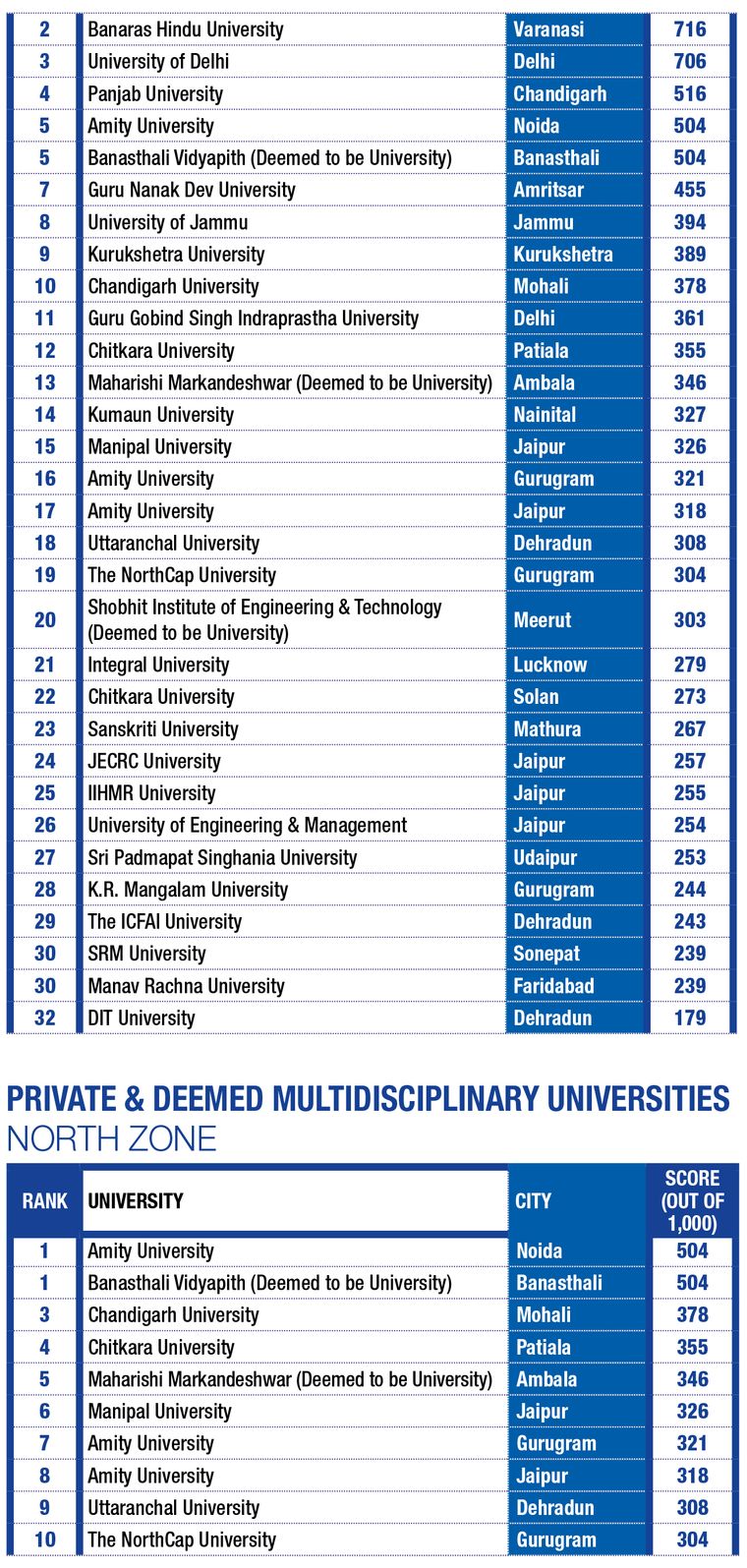

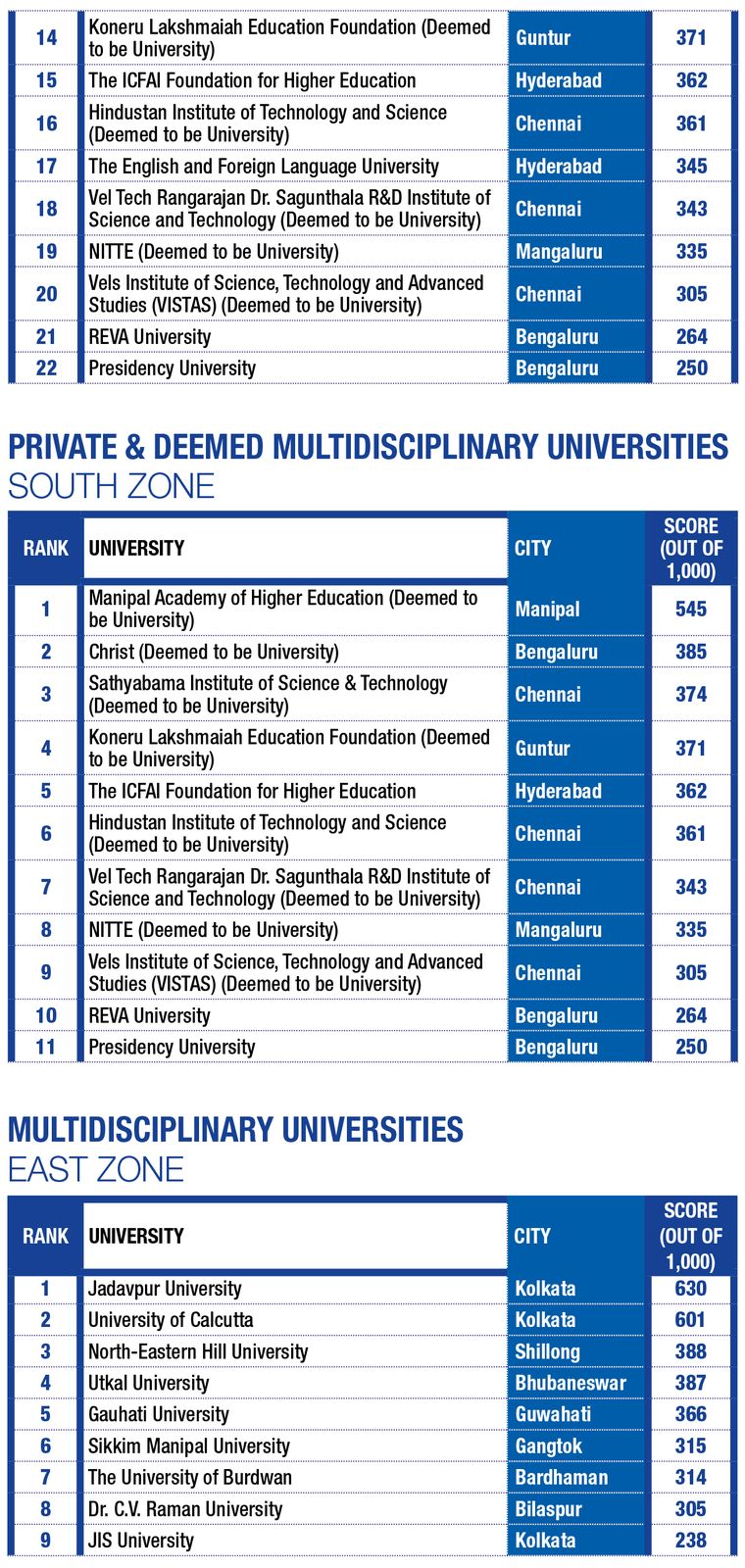

THE WEEK-Hansa Research Best Universities Survey 2023 provides insight into the hierarchy of multidisciplinary, technical and medical universities in the country. This year, the study was done across 15 cities.

To be eligible, universities had to be recognised by the UGC, offer full-time postgraduate degree courses in at least two disciplines and should have graduated at least three batches from the postgraduate programmes.

A primary survey was conducted with 302 academic experts, spread across selected cities. The respondents were asked to nominate and rank the top 20 universities in India.

Perceptual score was calculated based on the number of nominations and the actual ranks received.

For factual data collection, a dedicated website was created and the link was sent to universities. Fifty-four universities responded within the stipulated time.

Factual score was calculated based on information collected from universities and other secondary sources on the following parameters:

◆ Age and accreditation

◆ Infrastructure and other facilities

◆ Faculty, research and academics

◆ Student intake and exposure

◆ Placements (only for technical universities)

◆ Final score = Perceptual score (out of 400) + factual score (out of 600)

Some universities could not respond to the survey. Among them, for the universities which confirmed that they wished to be ranked, the composite score was derived by combining the perceptual score with an interpolated factual score based on their position in the perceptual score list.