AT A LARGE EXHIBITION named “Overcoming Gravity’’ in Kyiv in 2019, I bowed my head in front of her giant portrait. If you don’t recognise Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit, you might think that she is a teacher, a writer or a philosopher. No one would believe that she had studied only till grade four. She defied the system that branded people as ‘educated’ and ‘uneducated’, remained a devout believer in an atheist land, and loved her Carpathian lands deeply. And now I am in her homeland, right in the heart of her creative world!

Paraska took more than 4,000 photos, which surround us like waves in the ocean, reminding us of the lives and lifestyles of her forgotten ancestors. She is hailed as the Vivian Maier of Ukraine, a self-taught photographer, documenting life and nature around. But she is more than that. She created icons, paintings, drawings, and wrote books―theological works and prayers, fairy tales, stories and poetry―the range is as wide as it could be. She wrote 46 big books, running into around 500 pages each, and hundreds of small books, and all of them were handwritten. “My books are my children,” she used to say. Neatly folded and bound, stored in cartons or as scrolls, decorated with paper cuttings, all these were “hand made”! By one person, during the span of one life! Such items are so fashionable now. We diligently look for them in ‘fair trade’ stores and show them off when needed and not needed.

Paraska belonged to the Hutsul sub ethnic group from the Carpathian mountain region of Ukraine. She lived in Kryvorivnia, the village that famous writers like Ivan Franko and Lesya Ukrainka used to visit for inspiration. Serhiy Paradzhanov shot his famous film Shadows of the Forgotten Ancestors in Kryvorivnia. Once upon a time, when I was still a student at Presidency College, Kolkata, I dreamed of a chance to see those mountains at least once, after watching this movie. My dream came true. And I was rewarded with an additional gift―I found Paraska, and her deep love and respect for India.

Paraska was born on March 1, 1927, in the village of Bystrets in the Ivano-Frankivsk oblast in western Ukraine. Her father, Stepan Plytka, was a well-educated blacksmith and her mother, Hanna, a master weaver and embroiderer. The family moved to Kryvorivnia, when Paraska was one. She completed four grades in primary school, and was then tutored by her father, who also taught her German. During World War II, she worked as a translator with the village administration. In 1943, she travelled alone to Germany for higher education. Unfortunately, she was forced to work in a factory and as a housekeeper. She returned to Kryvorivnia and joined the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (which fought both the Nazis and the Soviet Union), where she worked as a liaison courier under the call sign “Lastivka” (Swallow). She was arrested on March 10, 1945. A Soviet military tribunal sentenced her to 10 years in prison. She was stripped of her civil rights and all her property was confiscated. Paraska and hundreds of women from western Ukraine were herded onto freight trains and exiled to Siberia. “Instead of warm clothes, they gave us oversized blood-stained overcoats that they had taken from the executed prisoners,” she remembered.

The Kolyma penal colony was cold and Paraska fell ill. Her feet were frostbitten. She stayed in the Ural prison hospital, where she was miraculously saved from amputation by a Georgian doctor. For almost five years, Paraska had to use crutches. In 1947, she was transferred to a special penal colony in Kazakhstan. In 1954, a year after Stalin’s death, Paraska finally returned home to her beloved Kryvorivnia. During her captivity, she fell in love with a Georgian painter. Although she managed to send his address home, her father destroyed the letter and did not approve of the relationship. Heartbroken, she stayed single all her life.

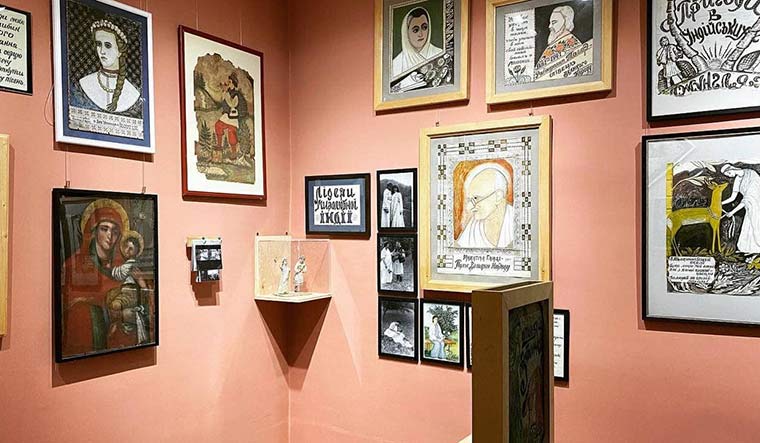

Preserving Memories: Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit’s home was made into a museum in 2022.

Preserving Memories: Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit’s home was made into a museum in 2022.

She lived on her own and never discussed her past life. She dedicated much of her time to prayer, and began painting and writing. She was hired as an artist by a local lumber company, and she used her first two salaries to buy a Smena camera, and a photo enlarger. Her work as a photographer brought her close to the villagers, who often asked her to take pictures of their families, children and homesteads. Her photographs depict a historical era, and her writings and paintings document the traditions of the Hutsuls that are becoming extinct.

She lived all her life in seclusion. Only in 1992, after Ukraine became independent, was she acquitted of all charges. A document dated May 27, 1994, less than four years before her death, announced the payment of compensation for her. Justice was not denied, but delayed. Her book Do You Hear, My Brother? Painful Poetry: 1944-1954, depicts the years of persecution, jail and exile.

Why did she love India? This remains a mystery. But Paraska was able to see beyond the veil of Soviet propaganda. Those were the times when the consumerist industries around curry, dances, movies, yoga, ayurveda and retreats were not yet globalised. India’s soft power had a different impact, when the word “India” was synonymous with the non-violent struggle of Mahatma Gandhi for Ukrainian and other Soviet political prisoners and dissidents. Since those days, Paraska carried India in her heart. She left a huge collection of paintings, drawings, stories, poetry, novels and portraits of Indian leaders. Many find these to be naïve. But I see a lot of divinity, sincerity and the total absence of mercantilism, calculation to stay in prominence―all that is hard to find today.

Paraska knew things deeply. Below the portrait of Mahatma Gandhi, she wrote the word ji, the sign of respect in Hindi. Only Indians call him Gandhiji. Below the portrait of Rammohan Roy, the father of the Indian renaissance, she wrote, “Great defender of widows”. It is even more interesting to see that in the portrait, Roy is holding a book in his hand, on the cover of which Paraska has written “Brahmo Samaj”. Briefly and clearly, in a single portrait, she tells the story about a person and an era.

She knew about the literature of India, and its great poets such as Subramania Bharati, and painted his portrait in which she wrote: “The morning star of Tamil literature. The poet tells us about the wonderful ancient culture of Tamil Nadu. India has millions of people, but the spirit is one, unbreakable.” Below the portrait of Amrita Pritam, she wrote, “Let there be no shameful flame of warfare on earth and air, let no poison be sprinkled on the seeds yet to germinate.” She painted two portraits of Rabindranath Tagore. In her house there are inscriptions and translations of quotes of Tagore that Paraska did by herself. She also made several portraits of Indira Gandhi.

She wrote a six-volume novel, Indian Glows, about the imaginary travels and adventures of two Hutsul women―she and her friend Theodosia―in India, as well as a graphic series, Adventures in the Indian Jungle and Leaders of a Peaceful India. The amazing drawings of Adventures in the Indian Jungle with poetic lines in Hutsul dialect are unique ethnographic material. Paraska even compiled a dictionary of the Hutsul dialect. Her imagination was also reflected in the fantastic drawings of Indian women in saris in the Carpathians, in the series “The fate of Hutsulka”. In the same series, she shows the hardship of Hutsul women, a topic of gender research today.

Paraska’s deep love for the preservation of Ukrainian culture is unparalleled. She is like a strong tree that stands on its roots and does not forget its ancestors or descendants. A typical representative of naïve folk art, she is now hailed as the Homer of the Hutsul lands. Paraska died in her village, in extreme poverty, alone and almost blind, on April 16, 1998. Only in the 21st century did Ukraine and the world find her.

In 2022, her hut, at the hilltop, was made into a museum. It will take years for anyone to study her legacy. She never travelled out of her village, but her spiritual journeys were planetary. Her philosophical reflections, recorded in the sweet Hutsul dialect, prove that despite having nothing, you still can create a universe―a university―for everyone.

Mridula Ghosh, formerly with the UN, now teaches at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, and also leads an NGO.