IN 48 HOURS, Sushma Kushwaha lost two sons, aged six and seven. Both were mauled to death by street dogs in Delhi’s Vasant Kunj in March. The postmortem found the cause of death to be dog bites on neck and abdomen. Not taking chances with the safety of her nine-year-old son Ansh, she sent him to her mother’s home in Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh. “I feel scared for him, too,” she said.

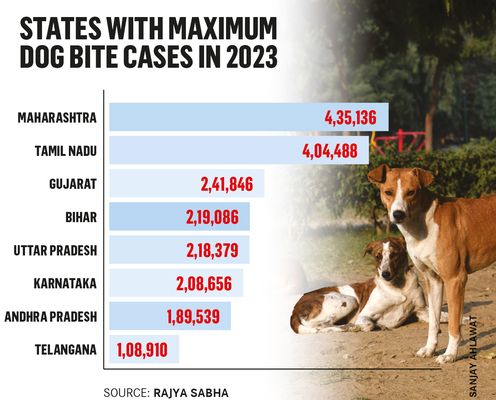

Kushwaha’s fear is not misplaced. Delhi sees 1,345 dog bites a month. It is no better across India. More than 27.5 lakh people were bitten by dogs across India in 2023. This includes an 11-year-old autistic boy, who died after being bitten by stray dogs in Muzhappilangad in Kerala’s Kannur district in June. In February, a pack of dogs mauled a four-year-old in Hyderabad. Shahwala village in Punjab rose up in anger following a boy’s death, demanding strong action against the stray dog menace.

“The situation has come to a point where parents are now scared to send their children out to play,” said Pranav Singh, secretary, residents’ welfare association (RWA), Urban Homes, Aditya Walled City, Ghaziabad. “We are doing everything at our end but the problem does not seem to abate.”

Here’s the biting truth: dog bites and rabies are emerging as serious public health and safety concerns. According to the World Health Organization, India accounts for more than one third of the world’s rabies deaths, with 18,000 to 20,000 people dying every year. The barks have reached the Parliament, too. On December 5, Parshottam Rupala, minister for fisheries, animal husbandry and dairying, told the Lok Sabha, “There are sporadic reports of dog attacks happening in various parts of the country. Number of dog bites reported in 2021, 2022 and 2023 are 17,01,133, 21,80,185 and 24,77,936 (till October) respectively.” Clearly, there has been an increase in the last three years. “India’s laws have made it difficult to control the stray dog population and ensure that all dogs are vaccinated,” said Ramanan Laxminarayan, founder and president of One Health Trust, a public health research organisation.

The Union ministry-run Animal Welfare Board of India (AWBI), which implements the recently amended Animal Birth Control (ABC) Rules, mandates “de-worming, immunisation and sterilisation by municipalities and panchayats to reduce the stray dog population in India”. Culling of stray dogs, which was permitted under the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (PCA) Act, 1960, was banned in 2001 when the Union culture ministry, with Maneka Gandhi as its minister of state, notified the first ABC Rules. These were superseded by ABC Rules, 2023, with not many changes in the process to be followed for animal birth control. The new rules, however, stress on more effective implementation and monitoring. Municipalities are advised to “hire own staff” for sterilisations and instal CCTVs “in places where animals are housed, including operation theatres”. This is a significant departure from the past when local bodies delegated the task to NGOs to execute the ABC programme.

The role of NGOs has been questioned by many. “There is huge corruption in NGOs involved in sterilisation work,” said Vijay Goel, former BJP minister, who is now running a campaign on the stray dog problem through his socio-cultural organisation Lok Abhiyan.

Even the RWAs are of the view that no one, including the NGOs, is doing anything significant to control the stray dog population, which is now estimated to be more than 60 million in the country. “NGOs play a negative role and do not contribute in resolving the problem,” said G.L. Mahajan, member, Saraswati Apartments RWA, Vasant Kunj. Added Yash Bhalla, 80, secretary, RWA, Saket, Delhi, “Senior citizens form 90 per cent of the population in our area. Dog bite cases have become very common. We call the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) but no one listens to us and the issue remains unaddressed.”

People working on ground, however, claim that their hands are tied owing to lack of funds. “NGOs do not have the capacity as they cannot meet the financial requirement, especially of arranging space to undertake sterilisation and vaccination,” said Abodh Aras of Mumbai-based Welfare of Stray Dogs. “NGOs have to depend on municipalities for budgets and the financial grants are very little. Municipalities should ensure that appropriate space is given for ABC programmes to run effectively. In Mumbai, there are only three spaces given by the civic body for such programmes, which explains the situation.” Agreed environmentalist Sonya Ghosh, who saves abandoned dogs in Delhi, “There can be a marked difference if we use about 77 animal husbandry hospitals and about 20-22 MCD-run hospitals in Delhi as dedicated spaces to properly sterilise the dogs in a sustained manner.”

The argument does hold merit. As per the 2022-2023 annual report of the ministry for fisheries, animal husbandry and dairying, which is the nodal ministry for animal birth control, NGOs and local bodies are eligible for a financial assistance of Rs370 per dog for pre- and post-operative care, including medicines and anti-rabies vaccine, and Rs75 per dog for catching and relocation.

The new rules seem to ask too much of the usually under-funded, understaffed and overworked district administrations. Ghosh believes that the new rules do not address the important issue of willingness and capacity of the local administrations to undertake this mammoth task. “The new rules by themselves are not going to help. Municipal corporations have been in charge since 2001 but not much has been done so far,” she said. “If you go to a MCD hospital, you can see that the doctors have not been trained.”

Among the many facets of the issue is the role solid waste plays. Kerala saw a 1,486 per cent rise in dog bite cases in 2023. Some attribute this to the banning of waste disposal in public places. “As we are moving towards cleaner cities, the food sources of strays are shrinking,” said Aras. “That is where the role of community feeders becomes important. It is like a balance that has to be maintained on grounds of compassion.” Ghosh sees these factors as “lateral arguments” and reiterates that sterilisation is the main problem. “If the basics are adhered to, the situation which we are facing today will not even arise,” she said.

Proper sterilisation is, indeed, a common ask. Lok Sabha MP Maneka Gandhi strongly believes that the “simple solution, which is also clear from ABC Rules, is to sterilise the dogs and put them back at the same place. If you sterilise the dogs and put them back, slowly the population will come down”. Aras cites his NGO’s experience of proper sterilisation programmes showing drastic reduction in dog bites. “Sterilisation breaks packs,” he explained. “If the packs are not there, dog bites will automatically come down as seen in places like Chennai, Mumbai, Goa and Sikkim.” Aras added that people, especially children, should be made aware about why and when a dog bites―it is usually when they are in heat or with their litter―so that such incidents can be prevented.

“I would suggest a national drive to spay and neuter all stray dogs of reproductive age, vaccinate them against rabies and other diseases, and allow for animal control to remove dogs that bite people,” said Laxminarayan. Agreed Goel, who inaugurated a Centre for Stray Dog Problems in Delhi. “Sterilisation is very important and is one of our demands besides vaccination and compensation,” he said.

In a significant ruling, the Punjab and Haryana High Court recently held the state “primarily responsible” for paying compensation. It ruled that a compensation be paid, from a minimum of Rs10,000 per teeth mark and Rs20,000 per 0.2cm of wound if the flesh has been pulled off.

The Supreme Court has begun hearing the stray dog issue after a bunch of pleas were filed, including by the Kerala government. The next hearing is on January 10. The apex court also took on a plea by Kannur district panchayat to euthanise “suspected rabid” and extremely “dangerous dogs”.

People in India have coexisted with stray dogs for generations. This coexistence is rooted in India’s Constitution, which beseeches compassion for animals and protects them through strict laws. Still, we seem to have reached a point where there are sufferers on both sides of the spectrum. “It is possible to have laws that balance animal rights and human rights, and the current laws serve neither dogs nor humans,” said Laxminarayan.

There is an underlying consensus that proper implementation and regular monitoring are key to get the desired results. Well-coordinated, well-monitored, well-funded and a wilful approach is needed to manage this peculiar human-animal conflict that is affecting several lives.