Chartered accountant Sanjeev Tiwari moved to Dehradun three years ago because his two children had developed breathing problems in polluted Delhi. Alok Shankar and wife Ankita came from Gurugram during Covid-19 and did not want to go back to the chaos of the National Capital Region. Deepak Longani gave up his footwear business in Delhi and has become used to the quiet and peace of the valley.

They are among several families from the NCR who now merrily dwell in Imperial Heights, a multi-storey residential society on Mussoorie Road, Dehradun.

“There are two primary factors for migration to cities in Uttarakhand, accessibility and climate,” says Subhash Pokhriyal, sales manager, Imperial Heights, who himself reverse migrated from Ghaziabad to give his family a better life. “There is a spurt in people from Delhi and NCR investing in Uttarakhand, especially since Covid-19. Many who bought flats in this society are non-residents.”

A similar pattern is evident in and around other cities on the Himalayan foothills like Haridwar, Rishikesh, Kotdwar, Kathgodam, Corbett and Haldwani. Investments in middle and higher reaches of Uttarakhand are also on the rise, but the numbers are low compared with the foothills.

A villa in Dehradun

A villa in Dehradun

A LocalCircles survey, with nearly 9,000 responses from Delhi, Gurugram and Noida recently found that 44 per cent of the respondents face various health issues. A survey by health care provider Pristyn Care in November 2023 found that six of 10 residents of Delhi and Mumbai are considering relocation because of pollution. According to a 2021 Knight Frank report, two in five respondents, across income segmaents, showed interest in buying a second home. The report highlighted that people were valuing air quality, proximity to green areas and access to good health care more.

Rakesh Ranjan, a developer in Uttarakhand, thinks that places like Dehradun fulfil most of the conditions that such buyers are looking for. “People are investing [in greener and affordable avenues] away from the capital, but within 300km,” he says. “This has inflated demand and the realty market in Uttarakhand is at its peak.”

Shalin Raina, managing director, residential services, Cushman & Wakefield, a global property consultant firm, says that the market in places like Dehradun have grown exponentially. “It has good health care, educational institutions and retail brands,” he says. “Enhanced connectivity and accessibility through roads and airport also make it viable for Delhiites to own property there.”

According to district records, there are nearly 2,500 government-run schools and 30 higher education institutes in the city. There are also around 100 private schools and approximately 20 private higher education institutions. Similarly, there are five top hospitals in or around Dehradun―AIIMS Rishikesh (around an hour away), the Government Doon Medical School & Hospital, the Coronation Hospital, the Shri Mahant Indresh Hospital and the Combined Institute of Medical Science & Research. Less than a year ago, Union Health Minister Mansukh Mandaviya laid the foundation stone for a new 500-bed hospital under the Pradhan Mantri Ayushman Bharat Health Infrastructure Mission.

“Potential in crucial sectors is huge,” says Pokhriyal. “The government must leverage it by creating necessary infrastructure.”

Urban areas are not the only places being increasingly inhabited by climate migrants. Doon Heights, about 25km from the city, is a residential colony in Dunga village. A serene patch of residential plots overlooking the Himalayan range, Doon Heights is surrounded by lush greenery and the Sone river is just half a kilometre away.

R.R. Verma, who retired from the environment ministry, stays there with his family. He says that most of the land owners there are from the NCR. “In the past one-and-a-half years alone, plottings have increased manifold in this area,” he says. “Most plot sizes in this area are around 250sqm-400sqm, and are bought by people who want an alternative from busy city lives. Of late, a lot of construction has also started.”

Property dealers attest to the increase in demand and land prices. Babu Rawat, a local dealer says: “In my 20 years, I have not seen so many people from NCR investing so heavily in Uttarakhand. Land that was being sold for Rs8,000-Rs9,000/sqm till a year ago has now gone up to Rs14,000 to Rs15,000.” The prices get higher closer to the city, he says, ranging from Rs20,000/sqm to Rs30,000/sqm. “Most importantly, people are willing to pay,” he says. Siddharth Dhiman, a local architect adds: “I am being contacted by a lot of people from outside for design approvals from the local authority.”

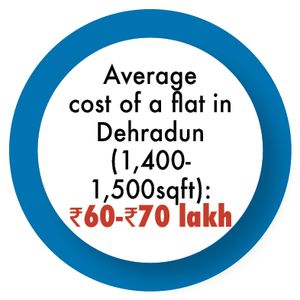

The promise of good returns on property is also driving people to invest more. “From an investment point of view the market is more viable as buyers can invest their money in bigger properties,” says Raina. Adds Rashmi Narula, sales executive of LA City, a luxury society on the Manduwala-Dunga road, “The prices for independent villas start from Rs1.1 crore whereas 1,500sqft-apartments range from Rs70 lakh to Rs90 lakh.”

The sudden influx of “outsiders” has not gone unnoticed by the local populace and ecologists. Says S.C. Arya, whose ancestral house is in Almora: “Land availability for local people is shrinking by the day. The demography, environment and the character of the state is changing. In the long run, it may not bode well for our children.”

Ecology experts also have concerns. Mashhood Alam, senior research associate, BRCG Research and Development Foundation, says that the rapid urbanisation and commercial development in Uttarakhand raise numerous environmental concerns. “Clearing forests for infrastructure, expanding urban areas and escalating pollution levels endanger essential habitats, fragmenting natural environment and depleting valuable resources,” he says.

Hemant Dhyani, member-coordinator of Ganga Ahvaan―an NGO working for conservation of rivers―is against the flourishing consumption-based economy in Uttarakhand. “Resource management comes naturally to local people who know the importance of a sustainable life,” he says. “They know how to respect nature, use its resources judiciously. But, people from outside who buy land to make big resorts and societies have only consumptive attitude and mindset. They are not sensitive to the sacrosanctity of the region. This will have an adverse effect on the socioculture and environmental fabric of the Himalayan state.”

Anoop Nautiyal, founder of the Social Development for Communities Foundation in Uttarakhand, says that the unabated, uncontrolled and unregulated urbanisation is the result of years of dilution of land laws in the state. “Dehradun has become a ticking time-bomb from where the developmental fault lines are [originating],” he says. “The situation is full of red herrings and has been acknowledged by the government also. It has also been flagged in the he Mussoorie Dehradun Development Authority’s (MDDA) draft master plan 2041.”

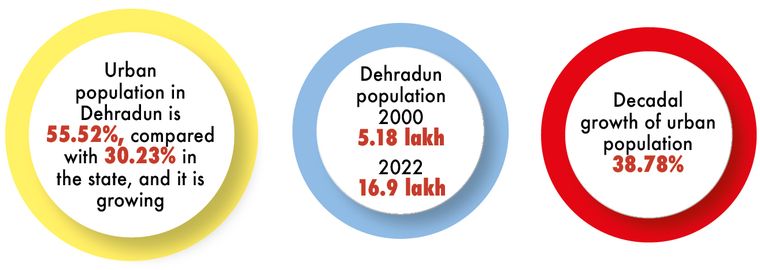

The population of Dehradun has increased from around 5.5 lakh in the early 2000s to 17 lakh in 2022. “Dehradun is being sandwiched between migration from upper reaches as well as plains,” says Nautiyal. “A mere observation indicates that it has far exceeded its carrying capacity.”

Mallika Bhanot, an independent environmentalist working on the Bhagirathi eco-sensitive zone adds: “The rapid influx of people from outside is going to massively affect the state, especially the resort construction that has been taken up at a scale not commensurate with the carrying capacity of the place. This will lead to overburden. Issues like dumping of solid waste, parking, electricity and water will spring up in a big way in the coming days. It is hoped that new laws will address these concerns.”

The first ever limit on land purchase by non-residents was brought by chief minister N.D. Tiwari in 2003 who capped it at 500sqm. This was further reduced to 250sqm by the BJP-led government of B.C. Khanduri. But, these restrictions were lifted by chief minister Trivendra Singh Rawat in 2017 to foster economic progress. This led to widespread investment into the state, especially on agricultural land. “The pretext of employment generation and economic progress is a myth,” Dhyani. “What [local people] get is fourth-grade employment (like cleaners and security guards). I do not think people want that.”

An agitation in December 2023 by a group of social organisations brought the issue of migration to the forefront. They took out a march demanding stricter land laws and a stop to large-scale sale of lands to “outsiders”. Concerns were also raised about issuing domicile certificates to non-residents. A singer, Narendra Singh Negi, penned a song ‘Utha Jaga Uttarakhandiyo’ to mobilise locals and said that the issue concerned the future of their children.

The Uttarakhand government was quick to respond. Chief Minister Pushkar Singh Dhami immediately formed a five-member committee to study the 2022 draft report that recommended amendments to the state’s land laws. One of the most important recommendations of the draft was the introduction of an essentiality clause like in Himachal Pradesh. In the essentiality test, necessity of the purchase by non-agriculturists and non-residents is gauged before issuing approvals.

The government, for now, has put a ban on sale of agricultural land. The MDDA has started a campaign against illegal plottings, which are now listed on its website. The environmentalists and locals are hopeful that strict restrictions will follow. “While there should be a blanket ban in the upper reaches of Himalayas, which are highly eco-sensitive, the capping in lower areas should be as low as possible for long-term sustainability of entire region,” says Dhyani.

“We understand that we live by our Constitution that allows anyone to buy property anywhere as common citizens of the country,” says Nautiyal. But, if action is not taken now, Bhanot contends, “the entire local ecosystem will be compromised”. To strike a balance, it is time, Mashhood suggests “to promote responsible investing in the region”.