Interview/ Dr R. Chidambaram, former principal scientific adviser to the government

A senior scientist during the Pokhran test in 1974 and chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission during the tests in 1998, Dr Rajagopala Chidambaram has been a key figure in the Indian nuclear journey. During both the tests, he led the design of the nuclear devices and the execution of the tests. Chidambaram, 88, still retains the fascination he always had for science. He continues to be engaged in research at the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre. He spoke to THE WEEK about the Pokhran tests, proliferation concerns and about global warming and climate change. Excerpts:

Q/ With new age domains like Artificial Intelligence and high tech weapon systems, are nuclear weapons passé?

A/ In the nuclear domain, you can use AI and other techniques only for protection when you move from one place to another. The thing about AI is a question of what you want it to do. Can you allow a machine to rule, a machine to learn and to perform tasks? But who teaches a machine? It is the human. So human beings will always be superior.

Q/ Does nuclear energy have a role in the fight against global warming and climate change?

A/ Climate change is caused by greenhouse gas emissions which prevent the infrared radiation from going out, and that is what leads to global warming. And as far as global warming is concerned, one of the worst things is the burning of fossil fuels. If you want to reduce the burning of fossil fuels, then one of the options is renewable energy, like solar energy. But solar energy is intermittent. You will have to store it, for which you need storage systems. In this context, nuclear energy becomes very important. It is sustainable and regular in its supply of electricity.

Q/ Are there proliferation concerns?

A/ Soon after India’s nuclear tests in 1998, two American authors, C.E. Paine and M.G. McKinzie, published an article titled “Does the US science-based stockpile stewardship program pose a proliferation threat?” They showed a Venn diagram indicating the sharing of nuclear weapons knowledge. Each country represented a circle. The intersection of the circles indicated sharing of knowledge either openly or secretly, or through spying and stealing.

Since the Manhattan project, the UK was closely involved in nuclear activities with the US. So the American circle includes within it a smaller circle, which is the UK circle. And the circle of Russia and China intersect. China and Pakistan intersect. The US and France intersect. France and Israel and four-five other countries intersect, and so on. But in that diagram, you find India standing alone without any intersections. It indicated that India spied on nobody, India stole from nobody. It was not needed because India had all the knowledge that was required.

An interesting fact in that diagram is the intersection of the US and Russian circles. And on that I don’t want to comment. I don’t want to get into the politics of it. You work it out.

Indians are, by nature, responsible people and India has always been a very mature country as far as its politics is concerned. And our political leadership is a very responsible leadership. That aside, the safety and reliability factor of India’s nuclear arsenal is very strictly adhered to. Everything has been taken care of.

Fifty years is a long time. But those were very interesting times. We had a brilliant electrical engineer called S.N. Seshadri. We were laying the cables in the Pokhran nuclear site from the control room to where the devices were to be exploded. And Seshadri was going around in a truck inspecting the cables. The truck driver said he had to go as it was lunch time. Seshadri told him that he would take over. That was the kind of drive we had. Unfortunately we lost Seshadri very early. There were minor things, but nothing serious.

Just after the 1974 tests, Dr Raja Ramanna, the main guiding force behind Pokhran I, asked if anybody got hurt in the explosion. Someone said it was only a crow that was flying near the nuclear site when the mound blew up and hit it.

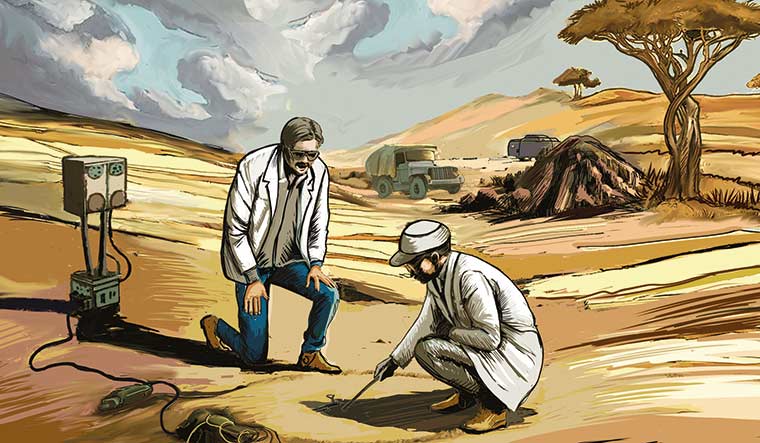

Before the 1974 test, I was walking around in the sand with BARC group director P.R. Dastidar, who had the key to activate the switches on the cables. Only Dastidar was authorised to operate the key after receiving the requisite clearances. As we were walking, the key popped out and fell into the sand. Dastidar got very nervous. I asked him to stay calm and not to move. I then drew a circle around the two of us so as to localise the place where the key fell. And then we found it!

What is remarkable about the Indian nuclear tests is that we did not get anything, including plutonium, from any other country. Plutonium is a very difficult metal to produce. We built plutonium plants and used that plutonium in the bomb.

Q/ Pokhran 1 was called Peaceful Nuclear Explosion (PNE). What does that mean? What differentiates a PNE from a test from which weapons can be made?

A/ US president Dwight Eisenhower wanted to start a programme called “swords into ploughshares”. The idea was to state that nuclear explosions can also be used for peaceful purposes. So Ramanna sent me to the US to watch the Rulison experiment in Colorado. Suppose you want to cut a canal. You have to explode a lot of chemical explosives to cut through. But one nuclear explosion can create a huge crater wherein it becomes much easier to cut the canals. Dr Ramanna had asked me to look out for its application in India.