When Narendra Modi took oath as prime minister for the first time on May 26, 2014, hundreds of foreign and Indian dignitaries had gathered for the event at the Rashtrapati Bhavan’s forecourt. Pakistan prime minister Nawaz Sharif was visibly uneasy and was sweating profusely in the Delhi heat. His aides looked around for a bottle of water, but water bottles had been prohibited as per the security arrangements. An Indian security officer noticed Sharif’s discomfort, walked up to him quietly and handed over a bottle of water he had stashed away in his coat pocket.

The summer sun is blazing once again, and with the country’s next prime minister set to take oath in June, the atmosphere is no different for the personnel on VVIP and VIP security duty.

“In the Indian context, VVIPs are the prime minister, president [and vice president], and visiting heads of state,” said retired IPS officer D.P. Sinha, who was secretary (security) in the cabinet secretariat and special director of the Intelligence Bureau. “There are other categories of VIPs who are provided security. The security officers are their body covers. It does not mean just taking a bullet. Threats must be detected and preempted.”

In 2014, after Modi landed in New Delhi on May 17, then chief of the Special Protection Group, K. Durga Prasad, briefed him about security concerns. While Prasad himself would not leave the side of outgoing prime minister Manmohan Singh (the SPG chief shadows the sitting prime minister till he demits office), he offered Modi an SPG team.

“Modi refused the offer,” said a person in the know, requesting anonymity. “He wanted his old security detail when he took oath.” So, in his moment of glory, standing behind him were the Gujarat Police officers and National Security Guard commandos who had protected him as chief minister of Gujarat. “It was thoughtful of the prime minister,” said the person.

Modi was driven to the Rashtrapati Bhavan in a Scorpio by his old detail and, after the swearing-in, he left in an SPG vehicle. In between, apart from Sharif, the security officers helped former Union minister Arun Jaitley’s son, who had fainted in the heat and they whisked away actor Salman Khan from autograph seekers. An officer said that Khan literally sprinted.

Most importantly, the ceremony was smooth. “Coordination is the key since security is a layered arrangement,” said a former security officer. “Each incident is taken note of by the nodal officers.” These notes add to the “institutional memory” of the VIP security wing under the Union home ministry―when an officer who was part of the swearing-in ceremony for successive prime ministers moved on to his next assignment, he tore off the handwritten notes and maps from his notepad and shared them with his successor.

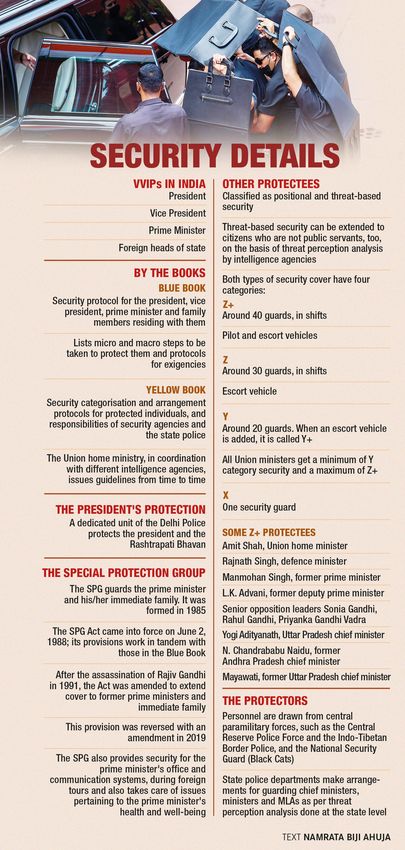

In India, the idea of providing security to political leaders was born after Naxalism became a threat in the 1960s. The SPG was formed in 1985, after the assassination of Indira Gandhi. The Union home ministry codified the protocols for protection in the “Blue Book” and “Yellow Book”. The names come from the colour of the covers of the books, slightly larger than pocket books, which were used to first write down the procedures, said former IB special director Yashovardhan Azad.

“The Blue Book explains the full drill and detail of protecting a VVIP or VIP,” said Praveen Dixit, former director general of police, Maharashtra. “It minutely details procedures for each and every scenario. It is updated regularly to keep track of new threats and challenges.”

The IB, which gathers domestic intelligence, naturally became the go-to agency for security of critical establishments and VIPs. State governments follow the Central government’s protocol with minor deviations here and there.

Under Modi, the SPG has had to change the way it worked. Former premiers such as Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh were known to consult their security detail before breaking protocol. But, Modi is more of a risk-taker. “Vajpayee or Singh also travelled less, especially towards the latter half of their tenures,” said an officer who oversaw security arrangements for the former two. “They did not campaign so much. Now, the election campaign exposure of the SPG is much more.”

The personnel closest to the prime minister constitute the close protection team (CPT). They act as human shields. But, Modi did not want many security men seen around him. As a result, the CPT for Modi mostly remains at a distance. “Manmohan Singh was a septuagenarian and officers had to move close to him to watch his step. But with a relatively younger Modi, there was no such danger (of stumbling) and the SPG did not mind keeping its men at a distance,” said another security officer in the know.

The last decade has brought new experiences and newer challenges, too, for the SPG, the NSG, and the multiple paramilitary and state police forces protecting VIPs. This is especially true during election campaigns when politicians take chances with their security. “The basic rule of VIP security is to avert danger in three steps―espionage, subversion and sabotage,” said Sinha. “This holds true for both critical establishments and individuals.” Jammers were introduced to block mobile signals when the security establishment realised that mobile phones could be used to trigger improvised explosive devices. Artificial intelligence poses a new kind of threat. The deep fake video of Union Home Minister Amit Shah this year demonstrated the importance of securing VVIPs and VIPs in digital spaces.

This election season Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister Jagan Mohan Reddy was hurt in the face when someone threw a stone at him. He was campaigning at night and all the lights were turned to him so that he could be seen by the crowd. But, this meant that security officers could not see the stone that came flying towards him. Officers admit it is a lesson learnt. “We must have areas around the politicians lit up,” said an officer. “If the lights were on people, a bold step like throwing a stone might not have happened.”

There are few politicians who worry about their personal security as much as the men and women tasked with protecting them. Former Tamil Nadu chief minister J. Jayalalithaa, however, erred on the side of caution. She always wore a cape, said an officer who protected her, “and no one could tell whether there was a bulletproof jacket underneath.”

Bahujan Samaj Party president Mayawati, too, likes impeccable cover, but when her security officer was caught on camera wiping dust off her sandals to protect her from slipping, she felt the controversy was avoidable. However, her reliance on personal security staff was such that she expected them to be aware of her political likes and dislikes. For instance, in 2002, she bumped into a young Akhilesh Yadav and his wife, Dimple, on a flight to Delhi. The couple greeted her, but she failed to recognise Dimple. Later, she scolded her personal security officer for not telling her that the young woman was Akhilesh’s wife. She was upset that she had not blessed the new daughter-in-law of Mulayam Singh Yadav’s family.

Twenty-two years later, the dynamics of both politics and VIP security have changed. Mayawati has been relegated to a distant third in Uttar Pradesh after Akhilesh joined hands with Congress leader Rahul Gandhi. The two leaders recently had to leave the stage without delivering their speeches, after a stampede-like situation at a joint rally. “It is not a personal choice,” said Dixit. “The people’s representatives have a responsibility to adhere to the advice of the security staff as miscreants can take advantage of a melee and launch an attack. There cannot be any shortcuts, whether you like it or not.”

There have been enough reminders of this. “When the SPG cover of former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi was removed [by the V.P. Singh government], even the advance security liaison was not conducted,” said Sinha. “We saw what happened in Sriperumbudur.” Rajiv and 15 others were killed, including superintendent of police T.K.S. Mohammed Iqbal, who had tried to stop the suicide bomber from entering the security cordon.

M.A. Ganapathy, former director general, NSG, said that IEDs became a weapon of choice for terrorist and insurgent outfits because of their low cost and low risk. In the times to come, he said, drones with explosive payloads would be a serious threat, and security agencies need to be well equipped and trained to meet the challenge.

Apart from threats, uneasy Centre-state relations are a challenge for the officers on VIP duty. “VIP security becomes challenging if there is federal mistrust,” said an officer, pointing to problems in states like West Bengal and Punjab. In Punjab in January 2022, Modi was stuck in traffic for 20 minutes. “The advance security liaison for the prime minister mandates the superintendent of police and the district magistrate to assist the three agencies―the Punjab Police, the SPG and the IB―in every step laid out in the Blue Book,” said Dixit, who was one of 27 ex-IPS officers who wrote to the president demanding immediate action against errant officers.

However, there are also positive tales of officers going out of their way to protect VIPs. In 2014, the BJP sent Amit Shah as election in-charge to Uttar Pradesh for the Lok Sabha polls. He was a state protectee and Manmohan Singh was in power in Delhi. The VIP security wing sensed that Shah was facing a high threat. It took the courage of one officer to recommend that he be made a central protectee. A few eyebrows were raised, but Shah was granted Z+ security. Shah was yet to become his party’s president.

There have also been notable lapses. In 2013, the IB dispatched hundreds of inputs to states where Modi held rallies. A few landed at the desk of the Bihar Police, which warned that Indian Mujahideen modules could make trouble during his Patna visit. The intelligence was correct and serial blasts rocked Modi’s political rally at Gandhi Maidan. Modi was safe, but red-faced central and state security officers traded charges. How to deal with overlapping jurisdictions when VIPs travel is also in the Blue Book, as then home secretary Anil Goswami pointed out when he intervened to resolve the situation.

Despite security lapses drawing criticism from the political class every now and then, VIP security duty is a coveted job. “It gives exposure, long urban tenures and an opportunity to travel and interact with political leaders around the world,” said an officer.

Manmohan Singh was known for taking care of families of officers posted with him. “There was always a personal touch,” recalled an officer. Vajpayee chatted a lot with his personal security staff and gave them sweets during festivals. “He gave gifts for family members and knew their names,” said an officer. “It was like a big family.”

In 2019, the Modi government withdrew SPG cover of Sonia Gandhi, Rahul Gandhi and Priyanka Gandhi Vadra and gave them protection by the Central Reserve Police Force. The transition was smooth, said an officer, and that the 28-year familiarity between the family and the security officers remained intact, unaffected by political exchanges over the SPG’s withdrawal.

However, VIP duty did become slightly uncomfortable when private persons started demanding VIP cover. “A few years ago, there was debate,” said an officer. “It was finally decided that only those private persons facing a high degree of threat can be provided central or state protection and that a fee would be charged from them.”

The government has rationalised such requests and is gradually removing the elite NSG from VIP duty to focus on counterterrorism. The VIP lists are also revised from time to time.

The best takeaway for security officers in recent years came after the visit of former US president Barack Obama for the Republic Day in 2015. This was the first ever foreign visit of a US president where he would be under the open sky at an event attended by thousands for considerably long hours. The two-way advance security liaison met the demanding requirements of the US Secret Service and representatives of 40 government departments. Unusually, the Secret Service agents even walked the entire route of the Republic Day parade to get a feel of the place and its spread. And, on January 26, when Obama watched the parade, an unprecedented blanket of security facilitated the warmth and camaraderie between the two heads of state.

On May 15, then joint director (VIP security) at the Union home ministry got a note signed by Obama. “I want you to know your dedication was an important part of the progress we made,” Obama wrote in the letter sent by the White House.

Two days later, Indian VIP security officers noted with joy as Obama walked under the open skies in Cuba, enjoying the rain, holding just an umbrella.