With all its contradictions and diversity, India has fascinated many. British economist and Indophile Joan Robinson, who observed India around the time the republic turned 25, remarked: “Whatever you can say rightly about India, its opposite is also true.” The statement appears to have stood the test of time as we celebrate the 78th Independence Day. It may still hold true when India turns 100 in 2047.

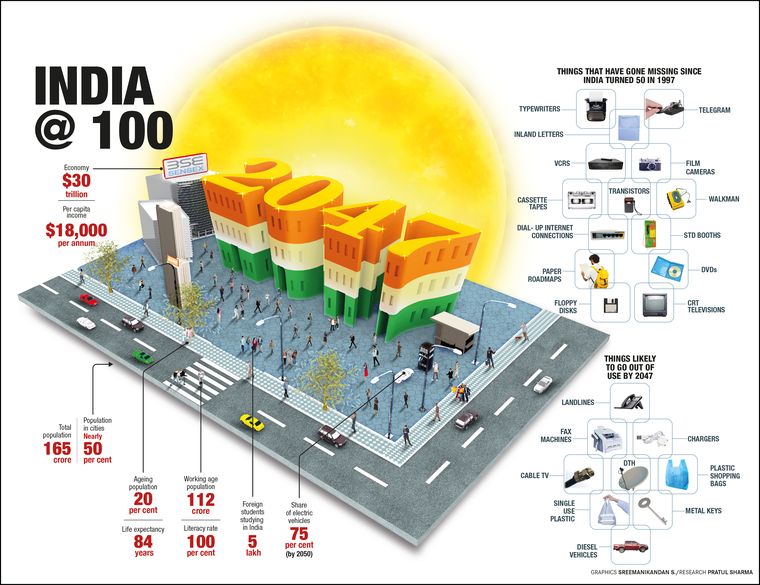

Prime Minister Narendra Modi had coined the term Viksit Bharat to nudge the country’s policy-making and political narrative towards building a developed nation and becoming the next superpower by 2047. A country with US$30 trillion economy by 2047, with a per capita income of US$18,000 per annum.

To meet the ambitious $30 trillion target, the GDP would have to grow nine times from today’s $3.36 trillion, and the per capita income would need to rise eight times from the current $2,392 per annum. Experts believe that it is a political target that would require deft manoeuvring and some big reforms. India, which has overtaken China in terms of population earlier than estimated, would overtake the US to become the second largest economy if it hits the GDP target.

India’s transition from the middle income to higher income group would require sustained growth in the range of 7 to 10 per cent for 20 to 30 years. Only a few countries have managed to do so in the last 70 years. “India has the potential, and aims to be a high-income country by the centenary of its independence in 2047. However, being a developed nation―a Viksit Bharat―cannot be reduced to a single monetary attribute. It would have to signify a good quality of life for individuals and enable a society which is vibrant, culturally rich and harmonious,” says NITI Aayog in its approach paper on 2047. When Modi unfurls the tricolour from the Red Fort for the 11th time (Jawaharlal Nehru unfurled it 17 times; Indira Gandhi, 16 times; and Manmohan Singh, 10 times) he is again likely to refer to his Viksit Bharat vision, which he first referred to in his speech on August 15, 2022, cajoling people to work towards that goal. His directive to his cabinet colleagues is to envision plans and policies towards the 2047 goal. This was reflected in the recent Union budget, which focused on “jobs, skilling, scaling up infrastructure and promoting resilience in agriculture and manufacturing”.

Independence Days are time to reflect on the past and plan for the future.

India’s strength lies in its demographic dividend. With a population of 144 crore, India is one of the youngest nations with a median age of 29 years. This accounts for nearly 20 per cent of the world’s total young population. This enormous opportunity is likely to last till 2047, before the population starts greying. People above 60 constitute 10 per cent of the population now. The figure will double by 2047, posing fresh challenges on the health care and social security fronts.

Half of India’s population is below 25. They have no memory of the time when India celebrated its 50th anniversary, in 1997, when two prime ministers―H.D. Deve Gowda and I.K. Gujral―lost power as allies withdrew support. At midnight of 14-15 August that year, Pandit Bhimsen Joshi sang ‘Vande Mataram’ and Lata Mangeshkar, ‘Saare Jahan Se Aacha’ to replicate the spirit of India’s Parliament, where Nehru had made his ‘Tryst with destiny’ speech 50 years ago. Marking the high point of the 50th anniversary celebrations was a boisterous march down the Rajpath on August 15 evening―telecast live by Doordarshan, with many traveling from abroad to be part of the celebrations.

The 50th anniversary brought hope and despair. A message that resonated in 1997 was the survival of Indian democracy with all its contradictions, and the need to stem out corruption, alleviate poverty and empower women. The message still resonates, as the resilience of the Indian Constitution is so inbuilt that even a murmur of changing it led to electoral reverses for the ruling party in the recent Lok Sabha polls. For the world’s largest democracy, which Modi calls the ‘mother of democracy’, the commitment to the Constitution is the only way to ensure an inclusive and harmonious society.

What has changed since then? The 1991 economic reforms had unleashed a consumerist society. It was difficult to imagine in 1997 how the country would look 50 years later. The hesitancy of the 1990s gave way to confidence in the 21st century, and the decades that followed brought political stability and the focus shifted to development. The vision now appears much clear.

There is a confidence now that India would advance in spite of who is in power. But the road to developed India would require sustained interventions from the Central and state governments to improve standards of living for people in urban and rural areas, ensure affordable health care and literacy of 100 per cent, and reduce infant mortality to 2 per 1,000 live births from the current 28.

Let us look at the positives. By 2047, 112 crore people will be part of the labour pool. There are now 1,168 universities, around 45,000 colleges and 12,000 independent institutions (up from 20 universities and 500 colleges in 1947), and a talent pool of 20 lakh STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) graduates created every year, more than 43 per cent of them women. The number is the largest in the world, and it is only set to increase. But these graduates would need skilling to prepare them for the global job market.

Are there enough local jobs? It is an area that needs government intervention and participation from industry leaders and entrepreneurs. The female labour participation is merely 37 per cent, it would need to go up to 70 per cent in 2047. India is currently ranked 122 in gender equality; it needs to be part of the top 10 to be a developed country.

The policymakers are also looking at the Indian diaspora, which is also the world’s largest. They account for $111 billion in remittances. “Indian-origin CEOs are now ubiquitous across the MNC world. This diaspora is the source of our strength, and can be leveraged to generate investment, attract technology, and create knowledge for India,” said NITI Aayog’s paper.

A big challenge would be to reduce the urban-rural income gap, increase the competitiveness of the manufacturing sector, reduce energy dependency, and prepare our cities to deal with the increasing influx of people. More than 50 per cent of the population would be staying in urban areas by 2047.

There are many challenges for India to become a developed nation by 2047, but it is a welcome start to even dream of that outcome. The journey would be the key. The idea of 2047 as a developed nation would flourish once it is framed as people’s idea so that they take ownership of it, rather then confine it as a political dream.

The idea would gain a life of its own when it is embraced by the people. THE WEEK invited some of the finest minds to imagine India in 2047, the challenges and the opportunities. They present a much granular picture of a nation in transition.

In the next two decades, our lives would have changed dramatically. Artificial intelligence has unleashed an energy that has made change inevitable. Climate change poses dangers like never before. Will the ‘developed’ or ‘superpower’ tag mean that inequalities perpetuated by caste, religion, gender or economic status would be eradicated automatically? Or would it require a much more concentrated effort and political will to eradicate those imbalances? Would Robinson’s words still be relevant in 2047? Time is upon us to reimagine the future.

To become a superpower, a country has to be self-reliant and capable in food security, energy sufficiency, defence, space and even sports. India’s bid for the 2036 Olympics showcases a confidence that may help in creating a sporting culture currently skewed in favour of cricket.

The success of democracies lies in improving the quality of life of their citizens. As futurist Alvin Toffler said, “Our moral responsibility is not to stop the future, but to shape it… to channel our destiny in humane directions and to ease the trauma of transition.”