It was a Saturday evening in 1999. Thoufeek Zakriya, a 10-year-old madrassa-going Muslim boy, held his father’s hand as he entered the storied Jew Street at Mattancherry in Kochi. Zakriya had been to many alleys in the city, but never one as distinctly pretty as the Jew Street, with its yellowish lights, old buildings and antique shops.

At the end of the street was the Paradesi Synagogue, first built in 1568 and reconstructed and built up over the centuries. In Malayalam, paradesi means foreigner; the synagogue had served many generations of Sephardic Jews who had migrated to Kochi from Spain, Portugal and West Asia.

But it was not the stories of exiled Jews that had Zakriya’s curiosity piqued, but rather the troops of tourists that streamed into the synagogue. When Zakriya and his father reached the synagogue, though, the gatekeeper said it had closed for the day. His father told the gatekeeper that his son had a burning desire to see the synagogue. Hearing him, a light-skinned man wearing a kippah (Jewish skullcap), who was lighting a lamp inside, came out and let them in with a smile.

As Zakriya took in the wall writings in Hebrew and an exquisitely carved Torah chest inside the synagogue, the man resumed what he was doing. Zakriya approached him, and the man said he was lighting the lamp to commemorate the death anniversary of a relative.

“If I close my eyes, I can still live that memory,” says Zakriya, now 35.

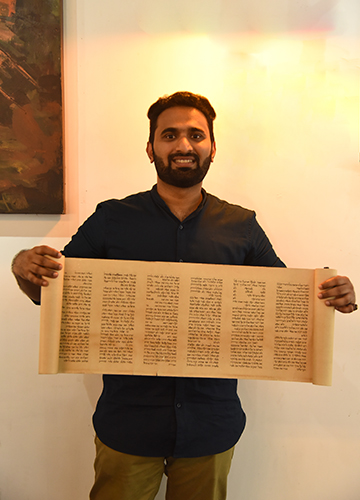

Zakriya’s life changed in ways he could not have imagined in the decades after his visit to the synagogue. He is now an internationally acclaimed calligrapher in, among other languages, Hebrew, Arabic and Samaritan, and a researcher on the history of the Cochin Jews. He learned Hebrew, a difficult language to learn, all by himself. In 2020, Zakriya, who is now based in Dubai, had the opportunity to present one of his calligraphic works to Israel president Reuven Rivlin.

Learning new languages and practising calligraphy have been Zakriya’s passion since his school days. Growing up in the culturally syncretic neighbourhoods of Fort Kochi and Mattancherry in Kochi so helped him that by the time he reached Class 10, he had created a set of characters that resembled Chinese which became a secret communication tool among his friends.

It was his exposure to Arabic in madrassa that helped spark his interest in Hebrew. “In madrassa, I learned the basics of Arabic to read the Quran, and heard many stories about Prophets Ibrahim, Ismail and Ishaq,” says Zakriya. “Later, at the convent school [where I studied], I learned the biblical stories of Abraham, Ishaq and Ismail. How the story of the same patriarchs [was told] from different perspectives fascinated me. It was then that I became curious about a third perspective, or the first perspective―the Jewish perspective. I asked people about the Jewish community in Cochin, of which I knew little. Soon I heard about Hebrew, their special language, which is similar to Arabic, written from right to left. This intrigued me.”

It was a Gideon Bible that had him learning Hebrew. “When I was in [Class 11], I saw a Gideon Bible in the school library,” he says. “I asked my teacher if I could take it, and she happily gave it to me. The preface had a verse from the Book of John in 25 different languages, [including] Hebrew… The English version had the word for God in it. I wanted to know the Hebrew word for God―that started my Hebrew-learning journey.”

Zakriya began by copying Hebrew letters. “I was practising calligraphy, although I didn’t know it was an art form at the time. I used pen, quill and bamboo sticks to copy text,” he says. In a shop that sold second-hand books, he found a volume that had Hebrew on one side and English on the other. “I couldn’t read Hebrew, but there was a prayer called the Kaddish at the end with a transliteration in English,” he says. “That was my Rosetta Stone.”

As he gradually improved his skills, a turning point came. “My friends and I used to spend time in the synagogue, simply enjoying the ambience. One day, a group of people, including the wife of an election commissioner, came visiting. Joseph Hallegua, a community leader, accompanied them. He opened the altar, the Heichel, and showed the Torah.”

Someone in the group said the Torah appeared to be upside down. Zakriya knew that Hebrew script can sometimes give that impression, so he spoke up: “No, no, it is correct.” The response was quite loud. Hallegua looked at him and asked how he knew. Zakriya replied that he had taught himself Hebrew.

As the visitors left, Hallegua asked Zakriya more about his interest in Jewish culture. Joy, the caretaker of the synagogue, suggested that he speak to Hallegua’s brother Samuel, a “walking encyclopaedia” on the history of the Cochin Jews and the synagogue’s gabbai (warden). Thus began Zakriya’s education in Jewish history.

But he received a jolt on the formal education front. “I failed my [Class 12] exams, even though my aggregate mark was above first class. I had failed in mathematics. It was depressing.”

Zakriya started learning Hebrew and Arabic with more vigour. “I used my old notebooks to practise my calligraphy. I also got acquainted with Samaritan, Syriac, Aramaic, Coptic and Greek. What I learned in that one year was not in any syllabus or curriculum. I was the teacher, student and principal of my own institute,” says Zakriya.

As an undergraduate, Zakriya studied hotel management, as his family was in the food business. “My father and paternal grandfather were in seafood export. On my maternal side, my great-grandfather had a borma (brick-oven bakery) and was known as Biskutakaran Musaliar for selling biscuits and being a learned Muslim priest,” he says.

Another reason for studying hotel management was that his father’s business was in decline. “I was a decent cook back then,” says Zakriya. “I referred to old recipes and practised cooking. After tasting my biryani, my father decided to send me to a hotel management school.”

For the final-year project of his four-year course, he focused on Jewish cooking traditions. He also continued calligraphing. In 2009, Zakriya took a friend to visit Jew Town in Kochi. He brought along ten different designs of Birkat HaBayit―a Jewish prayer often inscribed on wall plaques and displayed at the entrance of Jewish homes. At his friend’s instance, Zakriya showed it to Sarah Cohen, a venerable matriarch of the Jewish community in Kochi.

Cohen was taken aback. “She was quite surprised to see a Muslim writing Hebrew so well,” recalls Zakriya. “She repeatedly asked me, ‘Are you a Jew?’, and I told her, ‘No, I am a Muslim.’” The Birkat HaBayit plaque thus marked the beginning of a ten-year friendship that lasted till 2019, when Cohen died at the age of 96.

“She used to call me ‘aashane’ (a Malayalam word that means ‘master’, but is used to address friends); she was more like a grandmother to me,” says Zakriya. “Whenever I came visiting, I would bring her favourite snacks, achappam and kuzhalappam.”

Cohen used to host Zakriya for Passover Seders and introduce him to members of the dwindling Jewish community. On occasions, he cooked for her friends adhering to kosher rules.

“One day, she took me to the synagogue when prayers were about to start. Almost the entire Jewish community in Kochi was there. She took my family and me inside to show us the synagogue in its all glory. She said, ‘This might be the last time the synagogue is well decorated. I may not be able to show you next time.’ Nobody in the community said a word about bringing non-Jewish people into the synagogue during the service,” said Zakriya. “That was the respect she commanded.”

Having developed his unique calligraphic style, Zakriya began accepting requests from people abroad. One of his earliest patrons was a Ukrainian millionaire who presented him with a challenge. “He wanted a Hebrew scripture to be written in Arabic style,” says Zakriya. The result: a unique calligraphic work in the ancient Kufic Arabic script.

One of his most “emotional” works so far, says Zakriya, was for Juliet Hallegua, wife of Joseph Hallegua, who passed away in 2012. “She asked me to design his tombstone, and I did it,” says Zakriya. “As a tribute, she allowed me to examine the centuries-old Jewish Copper Plate (an artefact inscribed with privileges granted to the Jewish community by local rulers in Kerala).”

Over the decades, Jews in Kerala have mostly migrated to Israel, and Zakriya has become a keeper and chronicler of Jewish memories and artefacts. In July this year, when an ancient tombstone with Hebrew inscriptions was discovered on a coconut farm in Ramanathapuram, Tamil Nadu, Zakriya was called in. He was the first to decipher the inscriptions, which he dated to around 1225 CE. “This means that it is older than the Sarah Bat Israel tombstone in Kerala’s Chendamangalam, considered the oldest Hebrew tombstone in India,” says Zakriya.

Zakriya runs a blog and Facebook page named ‘Jews of Malabar’. Incidentally, it was a post on the page that led to his meeting with Rivlin in 2020. “[The post was] about the history of an 18th-century Hebrew Quran―which was the result of a work commissioned by a Jewish community leader in Kochi,” says Zakriya. “President Rivlin’s father, Yosef Yoel Rivlin, had also translated the Quran into Hebrew. Someone tweeted the [frontispiece] of that Quran, which was different from all previous versions of Hebrew calligraphies I had seen. So I made a small replica of the design, and posted it as a tribute. Rivlin saw it and wanted to meet me. Fortunately, just weeks before this happened, the UAE and Israel had established full diplomatic relations. This helped my journey to Israel.”

As a Muslim artist deeply connected to Jewish history and culture, Zakriya has faced questions regarding his stance on the Israel-Palestine conflict. He insists that he firmly supports universal brotherhood. “I believe everyone in this world deserves to wake up to a bright and beautiful day, to have a happy day, and to sleep peacefully,” he says. “Without any doubt, I stand with all those who suffer in this world; they all deserve peace.”