In the magazine Cartoonists India, former Reader’s Digest India editor Mohan Sivanand relates an anecdote about Shankar Pillai, one of the pioneers of cartooning in the country. In 1932, a few months after he had joined as a staff cartoonist with the Hindustan Times, Shankar got a summons from the viceroy, Lord Willingdon. Shankar met the viceroy with some trepidation, only to be welcomed with a broad smile and a pat on the back. He conveyed to the cartoonist how much he enjoyed his work. His wife, however, had one complaint. “Why do you draw my husband’s nose so long?” she asked him. Shankar explained how caricaturing entailed the exaggeration of certain features. “Now, even if I draw only that nose, people will know it is your husband,” he told Lady Willingdon. The Willingdons had a hearty laugh. Compare that with today’s India, when our leaders have lost their sense of humour so much that exaggerated noses will get them breathing down your neck.

It was not so in the first few years after independence. In fact, Gandhi himself was a great patron of cartoons. He realised their power in the art of protest. Right from his days in South Africa, when he was editor of The Indian Opinion, a multilingual paper he printed out of Johannesburg, he reproduced editorial cartoons from the British press in the paper. “The cartoons were displayed without any Gandhian austerity,” writes cartoonist E.P. Unny in his book R.K. Laxman: Back With A Punch. “They were generously flashed across full pages and on occasion front-paged.” Jawaharlal Nehru, too, enjoyed a good cartoon, even at his own expense. “Don’t spare me, Shankar,” he famously told the cartoonist. And Shankar never did. He is said to have drawn over 1,500 Nehru cartoons. In fact, a few weeks before Nehru’s birthdays, Indira Gandhi would access Shankar’s Weekly archives, choose a few Nehru cartoons, and frame and gift them to her father.

Many of the country’s top cartoonists, like Abu Abraham, O.V. Vijayan and P.K.S. Kutty, were mentored by Shankar. Caricaturing was having its heyday. “The cartoonists were stars then,” says Unny. “Until TV came, the most potent, comment-laden visual was the cartoon.” In the early days, we had a polity that was committed to press freedom. The cartoonists would freely mingle with politicians during every Parliament session, he says. There were no security restrictions. Those were the days when Nehru walking in Connaught Place was a common sight. The cartoonists needed to see the leaders at close quarters to draw their caricatures. Those days, the printing quality was not very good. Even while photographs came out blurred, line art would stand out. “The result was that, for many readers the primary impression of a politician’s face came from the cartoon and not a photograph,” says Unny.

R.K. Laxman, whose name has become synonymous with Indian cartooning, was of the same opinion. “The politicians were jolly good fellows,” he once said in an interview. “They never got angry. I have always had great friends among them. Perhaps privately they curse me, but when you meet them, sometimes in the plane sitting next to you, they say, ‘I liked your cartoon very much. It was one I told my wife she must see. But Laxman, you made a mistake.’ And they correct me as though they were the cartoonist. Rajiv Gandhi once told me, ‘I like your cartoons, but you make me look too fat’. It was a nightmare for me when he first came into the scene. He was not looked upon as a politician… so I had to create him. I lifted his nose, made him balder, shortened him and made him a little fat. People started recognising him by my caricature more than his person.”

If the politicians were gentlemen, so were the cartoonists. Their wit was acerbic, but never cruel. Rajinder Puri, another post-independence cartooning veteran, for example, relentlessly targeted Nehru, but when Nehru died, he paid a fitting tribute with a “cartoon grid filled with human forms that framed a void in the middle shaped like Nehru’s face”, writes Unny. These cartoonists were also never cowed by power. When Shankar, for example, was prohibited from drawing any more cartoons of C. Rajagopalachari by his editor at Hindustan Times, his response was another cartoon of Rajagopalachari, soon after which he quit and started Shankar’s Weekly.

Those were the halcyon days of Indian cartooning, but they were not to last. Shankar’s Weekly wound up in 1975, after Emergency was declared. “We could have taken the Emergency in stride, but the burden of running a weekly magazine on a shoestring was too much,” wrote Shankar in the last issue of the magazine. With censorship introduced during Emergency, mirth became a punishable offence, and so did Shankar’s stance that “everything that is laughable will be laughed at”. Even so, cartoonists found ways of letting their satire seep through the fine mesh of censorship. Abraham’s famous cartoon of President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed signing away ordinances from a bathtub, published in The Indian Express in December 1975, remains engraved in many an old-timer’s memory. “The irony was that a milder Laxman was a bigger problem for the censor than a politically explicit Abu Abraham,” writes Unny in his book. “The Abu cartoon left you in no doubt over who was being targeted over what. Laxman instead was oblique and ironical.” Laxman was summoned by the then Information & Broadcasting Minister V.C. Shukla and told that his celebrity status would not prevent the government from imprisoning him. So the cartoonist went on a vacation to Mauritius and returned only after the Emergency was lifted. Not that he did not extract his pound of flesh. His long-suppressed anger, writes Unny, was expressed in cartoons like the one of the Common Man literally delivering the punch and knocking down India’s Grand Old Party. “Another had Indira and her gang, complete with son Sanjay Gandhi in a pram, moving into impending exile across the Yamuna, where Muslims were herded at the height of Emergency,” he writes.

The country might have limped back to normalcy, but our politicians’ funny bones never really mended. Even as the cartoonists went up in arms―or brushes―against what they perceived to be abuse of power, our leaders used that power to still their brushstrokes. Hell hath no fury like a politician scorned. In 2012, cartoonist Aseem Trivedi was arrested in Mumbai for depicting the Parliament as a toilet bowl. In 2017, cartoonist G. Bala was arrested in Tamil Nadu for depicting a naked chief minister, E. Palaniswami, and two government officials. Cartoonist Rachita Taneja, aka Sanitary Panels, was served with a contempt of court notice in 2020 for criticising the Supreme Court, and cartoonist Manjul was warned by Twitter in 2021 that the government was asking for the closure of his account because of “violations of Indian laws”.

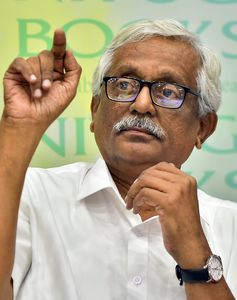

“I have faced several instances where my cartoons have attracted negative attention from authorities,” says Manjul. “From removing my cartoons from social media sites to putting pressure on editors and publishers not to engage me and threatening those who still carry my work, I have seen it all. Online abuse and backlash have become the new normal. The government micro-managing the criticism and increased scrutiny of my work are regular occurrences. These experiences highlight the precarious position of cartoonists in India today.”

Still, as Mark Twain once said, “Against the assault of laughter, nothing can stand.” Cartooning as a tool of rebellion was used as early as the sixteenth century by theologian Martin Luther. Engaged in a bitter feud with Pope Leo, and knowing that the only way he could get the support of the peasants who could not read was through visuals, he circulated posters and illustrated booklets which depicted biblical scenes that everyone could recognise and, next to them, the same pictures with caricatures of members of the Catholic Church as the antagonists. According to anthropologist David Thorn, this was the birth of the political cartoon. “Luther commissioned such artists as Lucas Cranach the Elder to make woodcuts in support of the Reformation, among them ‘The Birth and Origin of the Pope’…, which depicts Satan excreting the Pontiff,” writes Victor S. Navasky in The Art of Controversy: Political Cartoons and Their Enduring Power.

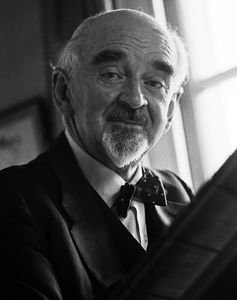

Some of the most powerful cartoons in the history of the art-form were drawn by Sir David Low―who inspired the likes of Shankar and Abraham in India―in the run-up to World War II. He produced regular caricatures of Hitler and Mussolini for London’s Evening Standard. “Unlike the vicious, cruel and revolting depictions in the Nazi weekly Der Sturmer, on the surface Low’s caricatures had an innocence, on more than one occasion showing Hitler as a spoiled brat,” writes Navasky. Once Lord Halifax, the British foreign secretary, upon his return from Berlin, described to Low’s publisher the impact of the cartoonist’s work in Germany. “You cannot imagine the frenzy these cartoons cause,” he said. “As soon as a copy of the Evening Standard arrives, it is pounced on for Low’s cartoon, and if it is of Hitler, as it usually is, telephones buzz, tempers rise, fevers mount, and the whole governmental system of Germany is in an uproar. It has hardly subsided before the next one arrives. We in England can’t understand the violence of the reaction.”

Low himself had an explanation. “No dictator is inconvenienced or even displeased by cartoons showing his terrible person stalking through blood and mud,” he said. “That is the kind of idea about himself that the power-seeking world-beater would want to propagate. It not only feeds his vanity, but unfortunately it shows profitable returns in an awed world. What he does not want to get around is the idea that he is an ass, which is really damaging.”

Perhaps an Indian parallel to the popularity and damage caused by the Low cartoon, though to a lesser degree, can be found in Laxman’s drawings of L.K. Advani post his rath yatra in 1990 with the “crown that clowned”. In Laxman’s portrayal of the yatra, the Indian leader was shown wearing a crown, “the kind that belongs to garish mass-produced spreads of Indian mythological figures”. Whether it was in his parliamentary work or public meetings, Advani couldn’t shake off the crown. For weeks this went on, until Advani fans were terrified that the whole of Mumbai was turning against him. “After scoring a raw point on faith-led politics, Advani was looking for living room cheering,” writes Unny. “The last thing he wanted was appearance after crowned appearance in the cartoon alongside the sober, self-effacing Common Man, the very picture of urbanity. The damage was cumulative over days and weeks. There was no early resolution. Laxman took his time to dethrone the leader and the buzz died a natural death.” Two years later, upon the demolition of the Babri Masjid, cartoonists once more collectively brought out their claws. They were so vehement in their protest that The Economic Times summed up 1993 as the year “when the line overtook the word”.

The cartoonists’ role in telling the truth is well-established, but not so is their role in predicting the future. While the cartoonist as protestor is visible to all, the cartoonist as prophet hides in plain sight. Take Shankar’s cartoon of Nehru published on May 17, 1964, on the eve of the Tokyo Olympics, which showed an emaciated prime minister staggering to the finish line of an Olympic race, with a few party leaders tailing him. Nehru died 10 days later. Another prophetic cartoon, cited by Sivanand in Cartoonists India, was on Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who was then prime minister of Bangladesh. In January 1975, he elevated himself to president. Shankar drew a cartoon warning Rahman that “Aladdin might take his lamp back”. He lost the presidency and his life when he was assassinated six months later. Low, too, was famous for predicting World War II through his cartoons.

Today, the action has moved from print to the web. With stick figures, punk art, graphic novels and comic strips, a new breed of young, internet-savvy cartoonists has migrated to Instagram. Still, cartoonists remain as prescient as ever. That is why THE WEEK asked eight popular Indian cartoonists with a sizeable presence on social media to draw on the future of India. How hopeful or bleak do they perceive it to be? What does the lay of the land look like from their vantage? Can their humour in any way douse the embers of religious, political, and social unrest smouldering in the India of today? As Sivanand writes, many years ago, Shankar’s Weekly ran a tongue-in-cheek article titled Sovereign Theocratic Republic: Draft Constitution of Bharat. It promised for all its citizens: “Justice, theocratic, plutocratic, and autocratic. Liberty of marriage and faith in cow-worship. Fraternity, assuring the dignity of the Hindu and the oneness of the nation.” He could have been talking about today, but who’s laughing?