JUST HOW SIMPLE or complicated can a chess player’s career be? With five world championships and having contested in countless top-level tournaments, India’s first and finest grandmaster Viswanathan Anand talks about all this and more in his autobiography, Mind Master. Written with journalist Susan Ninan, the book is of a similar, impeccable standard as that maintained by Anand throughout his career.

It is what goes on behind the scenes that is enthralling—almost like preparing for war, each player has his own army of trainers, seconds, managers and advisers, all shrouded in a thick veil of secrecy. Anand takes you inside that world. It reads the way he speaks—clear, articulate and descriptive.

He started playing top-level tournaments at a time when Soviet Union players ruled world chess. Anand’s achievements get magnified further because he broke through the Soviet wall without any peers or predecessors at home to rely on.

He does not shy away from talking about the tough times. In fact, he confronts the low points and challenges in his life. Anand also writes about the time he now gets to spend with his wife and son, the beauty of taking on the younger generation and the advent of artificial intelligence in chess.

Excerpts from an interaction:

Was writing this book cathartic?

Bits of it are. Invariably, in a book you have to be honest. You have to share things you would [otherwise] not share. But overall, I do not feel a need for catharsis (laughs). I did enjoy it a lot. Especially confronting all the stories I had forgotten, the details get mixed up. But when you are forced to write a book, you check the facts, check with others, exchange memories and my seconds tell some stories. You realise that other people remember things differently.

You talk about your initial years, where it was the Russians versus you. How did you cope?

It was a myth in our heads, and it still is. The first time I went to the Soviet Union, you had a feeling that every taxi driver knows chess more than you. This is a myth. It was a different country where chess had a different status. There were a lot of players who used to think the KGB was tracking them and things like that. I say all these things with irony and also try to recollect how naive we were.

Over time, I developed a good relationship with a lot of [Russians]. It is a country I enjoyed visiting, but it was a more closed society. At the same time, ‘Russian’ can also mean very high standards of chess training and a knowledgeable audience.

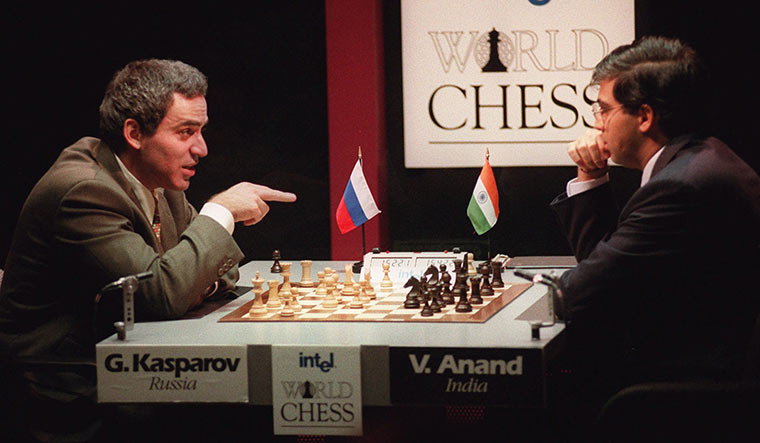

How did playing the likes of Garry Kasparov, Vladimir Kramnik and Veselin Topalov impact you in your initial years?

In those days they were the best players, so it affected you all the time. They had a training system where the same coach would be for two guys and [yet] they had completely different styles. I learnt that all you can do is maximise your own strengths.

Another thing is that it is very easy to fall in love with your own opinion and your perspective in chess. So for me the most revealing moments in chess are often when the assessment or strategy of somebody who is equally strong in his understanding of chess is so different from mine.

Do you have a better relationship with Kramnik and Kasparov now?

Kasparov was already world champion for about six years before Kramnik and I started playing top tournaments. When he met us, there was already a barrier. We were never that close. We were rivals and we were friendly, but not friends.

Kramnik, [Boris] Gelfand and I are the same age. I have gone for dinner with them more often than I have with Kasparov. The second thing is, with Kramnik, I have always been friendly, but I have tried to bring out in the book how when two good friends want the same thing, tension creeps in. Like any relationship, it has gone through its ups and downs.

The relationship improved when he offered to help me with the match against Topalov (2010 world championship). It changed the way I saw him. To be honest, our rivalry had subsided a lot by this time. Both of us had to deal with younger rivals then.

What about Kasparov?

The same thing happened with Kasparov. When he retired, he helped me. From 2010 to 2015, we were not on speaking terms because of the [FIDE] presidential elections. We just started talking again in a tournament in St. Louis. There was a lifetime of shared experience that nobody else could match. Also, what is the point of pretending we do not like each other? That is not to say we are bosom buddies or we visit each other’s homes. But there is an acknowledgement that we have this relationship.

One of my favourite stories is about Kasparov and Karpov, who had serious disagreements, way more than what Kasparov had with me. But once they were on a plane together, they would play cards. I was very influenced by this story. At that moment, you might exercise self-control. Also, if you keep bottling anger and hatred, it consumes you.

World championship matches in Bonn, Tehran, New Delhi, Chennai and Sofia have all been different. Which one of these matches has left the deepest mark on you?

These are the high and the low points in my chess career, not necessarily emotionally. Chennai really brought my world championship career to an end. Bonn had the best match I ever played. They are very significant emotionally. But in my book, we also try to cover other moments that I recall with great fondness or great pain.

Among the new generation of Magnus Carlsen, Wesley So and Hikaru Nakamura, who do you think is the most creative?

That is impossible to answer. I would say you can easily answer who is the most successful—right now, it is Carlsen. I think many people are creative in different ways, but unless you understand why you are being creative and perform well at high levels of the game, success can elude you to the same degree.

What I find interesting about this generation is that they are very undogmatic. Thirty years ago, we would have strong opinions of how chess should be played. Nowadays, thanks to computers, people will say any move is good as long as you can follow through. It shows your approach has changed. The younger generation will do a lot of stuff that older generations struggled to learn.

Mind Master: Winning Lessons from a Champion’s Life

Author: Viswanathan Anand (with Susan Ninan)

Publisher: Hachette India

Pages: 272 Price: Rs599