When the clouds unzip and drench the green, hearts sink across the land.

For years now, rain has been a villain in cricket, for fans to shake their fists at and swear. And for M/s Duckworth, Lewis and Stern to cop a few verbal blows, too. But, for all of its abilities to play spoilsport, rain did give birth to the vehicle that drove cricket into the future—the One-Day International.

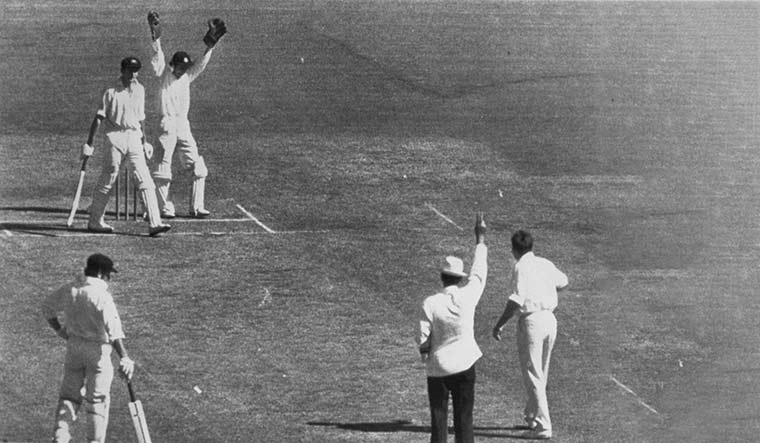

During the 1970-71 Ashes tour, a rather ill-tempered series by several accounts, a downpour had marred the third Test. The first three days were washed out and officials, looking to salvage the situation, quickly arranged a 40-over match. The Englishmen were not too keen on playing the truncated tie; Australian Cricket Board chairman Don Bradman, though, gave it a thumbs up.

“We didn’t take the game particularly seriously,” England captain Ray Illingworth told Sportsmail earlier this year. “The Australians were paid a full match fee and we weren’t paid much at all. We were there to win the Ashes and I didn’t want anyone to get injured. That made this game a bit dodgy.”

The Australians eventually won by five wickets, but the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack of 1972 did not carry a report of the match. It was thought to be a one-off and, hence, deemed unworthy of a place in posterity.

But, there was an undeniable spark.

A few false starts later, the inaugural World Cup was announced. The West Indies, led by Clive Lloyd, won the tournament. India won just one match, against East Africa.

But it was two years later that a burly Aussie would drag cricket, much to the chagrin of the gentlemen custodians of the game, into a new era. Media tycoon Kerry Packer had reached into his deep pockets and signed more than three dozen of the world’s leading players for a rival tournament to compete with the Australian season. The white ball, floodlights and regular use of coloured clothing were some of the innovations World Series Cricket brought, along with more money for the cricketers. In his book And God Created Cricket, journalist Simon Hughes wrote: “[Michael] Holding had only ever had a few hundred dollars in his post office account. When he got home after WSC and checked his account he was astonished at the amount. ‘It was the first time I’d seen a comma in that book,’ he said.”

Commentator Mark Nicholas wrote in his book A Beautiful Game: “Packer changed and improved cricket. He emancipated the players for their benefit and for his. To some it was a scandal, to the rest of us it was a brave new world.”

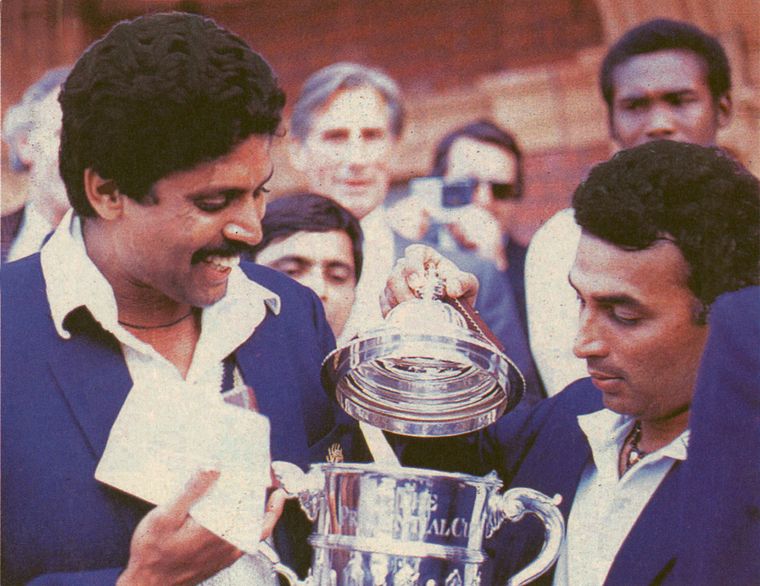

And it was in this brave new world that a lanky lad from Haryana led the unheralded Indians to their first World Cup win (then Prudential Cup) in 1983. What Kapil Dev and his men did arguably opened the eyes of many cricket playing nations to the possibility of reaching the pinnacle in a sport largely dominated by England, Australia and the West Indies.

David Frith, the editor of Wisden Cricket Monthly, had written: “Show me a person who gave Kapil Dev’s team any chance of winning the 1983 World Cup and I will show you a liar and an opportunist.”

He ate his words—literally—after the tournament. The publication put out a picture of him trying to wash down the inked-paper with what seemed to be red wine.

For some purists, the shorter format was as unpalatable as that paper was to Frith. The One-Day game was more result-oriented and brought some sense of urgency to the game. The shots became more attacking, the bowling more inventive and the fielding livelier. The third umpire was introduced and games would be live till the last ball.

Being shorter than Tests also meant that there was a chance that the better team might not always win. There was not enough time to rebuild after a bad session, like in Test cricket. A couple of slip-ups could cost you the game. For instance, Sri Lanka—winners of the ODI and T20I World Cups—have only beaten Australia four times in Tests, and that too at home.

This encouraged more and more teams, and broke the dominance of the few. With ODIs, cricket spread to more countries, earned more from advertising, and became more exciting to the casual fan.

In India’s case, the boom of ODI cricket coincided with the opening up of the economy in the early 1990s; television sets sprouted in homes across the country, and new channels filled them. Watching coloured clothing on colour TV was a thrilling prospect, and it only became better with events like the Desert Storm. Sachin Tendulkar hit back-to-back centuries in the 1997-98 Coca Cola Cup against Australia in Sharjah. It was one of the most memorable moments in ODI cricket, and there was plenty more to follow. Be it the 438 run chase by South Africa or the first 200, by Tendulkar.

The latest of the more memorable moments came in the final of the 2019 World Cup in England. A throw by Kiwi Martin Guptill hit Ben Stokes’s bat as he dove to the crease and went to the boundary. There was a Super Over, and England won the World Cup by virtue of hitting more boundaries.

There was controversy, there was drama and there was excitement. It was a moment that highlighted the value of One-Day cricket; something that a section of fans had been questioning for a while. Some critics of the format had been saying that the well had run dry, and that the 50-over game faced an identity crisis.

Which brings us to the question: Now, having completed 50 years, where does the middle child of cricket stand? Former New Zealand captain Martin Crowe wrote this is 2014: “Let’s see it settle the one-day game into 40-over mode, remove the gunk in the middle, keep it simple, stupid, and hey presto, every captain will be positive about the format that is still the life blood of our fine game. If not after the World Cup, then the one-day game will evolve within the next four years. It’s inevitable.”

Sadly, Crowe did not live to see whether his prediction would come true. It did not, at least not to the extent he wanted.

Many of the gripes persist. For starters, the trite observation that cricket nowadays is an “uneven contest between bat and ball”.

South African pace man Dale Steyn even said that ball tampering incidents could be seen as “a cry for help”. In the aftermath of Sandpapergate in 2018 (three Australians conspired to alter the nature of the ball using a foreign substance during a Test in Cape Town), Steyn said: “Fields are small, two new balls (takes out reverse swing), powerplays, bats have got bigger than they used to be… the list can go on. You bowl a ‘no ball’ and it is a free hit. But I have never seen a rule change that favours the bowler.”

Then there is the question of meaning; there is “no contest without context”. The bilateral ODI series, in particular, has been a punching bag, with even some former cricketers taking their shots at it. “What I would like to see more is some significance attached to a bilateral series,” former Australian batter Dean Jones told Deccan Chronicle in 2017. “Otherwise, the mediocrity of these stupid and meaningless one-day bilateral series is not going to help the sport. We need more triangular series. Isn’t it fun to have India, Australia and South Africa featuring in a tri-series?”

Former Indian cricketer Aakash Chopra told commentator Harsha Bhogle on a show in 2019: “By the fifth match (of a series), you don’t even remember, while covering it, who scored runs in the first game, who got out how in the second game… it doesn’t really add to the drama and there are far too many [matches]. In a 100-over game, there are at least 45 to 50 overs where nothing happens.”

In a video on Chopra’s YouTube channel, former Indian batter V.V.S. Laxman said: “It’s become a bit predictable. If the wicket is flat, the bowlers will be under pressure. If the conditions are bowler-friendly, then you won’t get to see the big shots. There’s a set pattern. The wicket matters a lot in ODI cricket.”

Two countries playing five or even seven ODIs in a series could be boring, especially if the teams were mismatched. There was nothing larger at stake and there would often be dull dead rubbers. The ICC has tried to remedy this by introducing the ODI World Cup Super League—points will be on offer in every ODI and teams will have to qualify for the tournament in 2023 based on those points. However, there might be limited interest in India as the team has already qualified; it is the host.

There is also the burnout aspect. As early as in 2009, a survey conducted by the Australian Cricketers’ Association (ACA) showed that 80 per cent of cricketers believed they played too many one-dayers, and 75 per cent of those considering walking away from one format to prolong their careers would do so from ODIs.

And as for Jones wanting triangular series, the last tri-series featuring any of the top three—India, Australia or England—was back in 2016. Several reasons have been cited for culling three- and four-nation tournaments, including less profit (because people would not turn up for neutral matches), and the packed schedule owing to domestic T20 leagues.

The growth of T20s made a lot of viewers crave pace in the game. But ODIs were not providing that. Even between top teams, the middle overs—11 to 40—usually saw a sort of truce between the teams; the batters would look for singles and twos and not take risks, and the bowlers would be defensive. Since the 2015 World Cup, though, the Eoin Morgan-led England have changed this. The team has been aggressive throughout the innings and its brand of cricket made the game more watchable, and eventually led to a World Cup win.

It is also in England that the next format of cricket was introduced this summer—The Hundred. It was shorter than a T20, and was aimed at children and teens. If ODIs were envisioned to take the game forward and provide a result in a day, then T20s, and now The Hundred, did that much faster.

For all its initial success in bringing other nations into the fold, T20s have now taken over that role. The 2019 ODI World Cup had only 10 teams. The T20I World Cups have more. If an upset is possible in 50-over cricket, it is likelier in the 20-over format. And that will pull in more nations to play the shortest format. That cricketing administrators are looking to use T20 as the platform to drive growth is evident by the fact that the US will co-host the T20I World Cup in 2024.

As for ODI inclusion, the last time Zimbabwe met any of the Big Three—India, England and Australia—on the field, the world was yet to hear the words ‘President Donald Trump’. India whipped them 3-0 in Harare in June 2016.

So, if T20s are the future, what about Tests? While the longest format has its own problems, it seems to be more secure in what it is. The band of purists swears by Tests; it is a test, they say, and it mimics life itself. That the past few years have seen some cracking, closely fought, see-saw matches has only bolstered that image. In 2019, the Marylebone Cricket Club conducted a survey of more than 13,000 responders from over 100 countries—an average of 86 per cent placed Test cricket as their preferred format to watch, follow and support over ODIs, T20Is and domestic T20s.

The previous year, the ICC had conducted its first global market research survey; close to 70 per cent of the 19,000 global cricket fans interviewed were interested in Test cricket. T20I was the most popular format with 92 per cent interest, while ODIs were at a high 88 per cent interest (contrary to popular belief). Although, how much of that 88 per cent included the World Cup, the most popular event, was unclear.

Over the years, there have been some ideas on how to generate more interest in ODIs. On a YouTube show last year, journalist Nikhil Naz suggested that the pitches need to be “spicier” and that ODIs should go back to using just one ball. This would bring reverse swing back into the game. He also batted for more overs for bowlers; there is no limit to the number of overs a bowler can have in a Test.

Tendulkar had, some years ago, proposed that the ODI match be converted into four innings of 25 overs each. This would neutralise the dew factor advantage, make the rain rule more manageable and make broadcasters happier—there will be more innings breaks compared with the one long 45-minute break in the middle.

To be fair, the ICC has made some moves to make ODIs great again. The Champions Trophy, for instance, has been brought back. The last edition was held in 2017, in which Pakistan beat India in the final. Apparently, it was reinstated due to its popularity, which flies in the face of the argument that it was a pale shadow of the World Cup. The decision also indicated that a multi-nation tournament would always bring in the fans.

Also, to make the game more inclusive, the 2027 and 2031 ODI World Cups will have 14 teams each. One of the reasons cited for making the World Cup more exclusive was that broadcasters were spooked by India’s early exit in the 2007 World Cup, which had 16 teams.

Dev said on Chopra’s show: “When you see so many T20s and so many close finishes, you feel like the ODI format is drifting. This will happen for a while, but ODIs will come back stronger. In some time, there will be more exciting matches. There was a time when people thought Test cricket was over. But if you see the recent matches, Test cricket has become a lot more engaging. The results are close and draws are done. Like this, perhaps ODIs will also become more engaging.”

As Holding said in an interview last year: “I don’t think ICC will ever get rid of 50 overs cricket because that’s one of their biggest earners as far as TV rights is concerned. The money will be slashed drastically.”

And if money can’t help, what can?