It is early morning, but heat and humidity hang heavily over the Musahar settlement of Manjhi Tola of Harivanshpur panchayat, Vaishali district. As we make our way to the house of Sunny Kumari, one of the seven children in the panchayat who died in the Acute Encephalitis Syndrome (AES) outbreak in June, what is more oppressive is the destitution enveloping every individual, especially kids. Naked and mud-caked children—many of them with obvious signs of malnourishment like shrunken limbs, dilated stomach and discoloured hair—dot the settlement, mostly in the care of slightly older sisters. A few roam around aimlessly, while others eat whatever they have—from dry, leftover chapatis to palm fruits and rice soaked in water. Three lucky ones, however, happily munch on mini snack packages, probably from a roadside kiosk.

About a kilometre away, in anganwadi number 91, helper Sona Devi claims she has made khichdi for children—providing a “hot cooked meal” is part of the supplementary nutrition programme of the Integrated Child Development Services. But a peek into her aluminum vessel reveals nothing more than boiled rice, just enough for seven children. There is not even dal. In the outer room, nine girls wait for this “nutritious diet”. None of them is from Manjhi Tola, even though the settlement falls under the anganwadi’s jurisdiction. Sona defends the meagre quantity of food, saying not many children visit the centre, but she is unable to explain the menu.

Back in Manjhi Tola, we meet Sunny’s grandmother Munakia Devi, who lives in a concrete house built under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana. Most houses here are brick structures, but many do not have doors. Munakia says her house gets flooded during rains. Her daughter, she adds, left for her in-laws’ village soon after Sunny’s death as she was worried about the health of her two other children. Munakia insists that Sunny was quite healthy and had dinner the night before she died. Did they always have enough to eat? A tentative yes is her answer. Was Sunny enrolled in the local anganwadi? A firm no is the reply.

Sunny, as per her Aadhaar card, turned six this May. She had never been to the anganwadi, nor had the six other children who died in the panchayat—four of whom were below six years. “They were not registered as they were healthy,” says anganwadi worker Ibha Kumari. But, how does one define healthy? Close to Sunny’s house live Anushka Kumari, 3, who looks younger because of her shrunken body, and her pregnant mother Mintu Devi, 20. They, too, have not been registered at the centre, says Mintu. Several other Musahars, a highly deprived Scheduled Caste community, here say that their children have never been to the anganwadi.

This deprivation is because Bihar has a shocking system in place. Under ICDS, which is now covered under the National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013, all children who are six months to six years old and all pregnant and lactating women should get supplementary nutrition, either as take-home ration or hot cooked meal from the local anganwadi. They are also entitled to regular growth monitoring and severe acute malnutrition management.

But Manjhi Tola reveals a different reality. Ibha says the anganwadi covers about 230 children and 37 pregnant and lactating women in the settlement. But she provides take-home rations to only 45 children under three years and 16 women, and hot cooked food to 35 children of three to six years. “That is the norm,” she says. So, 150 kids and 21 women are simply left out.

The children are selected through a quarterly survey, says Ibha; their weight is checked and the weaker ones included in anganwadi. Inquiries reveal similar limiting of numbers at several anganwadis across Muzaffarpur, Siwan, Gopalganj, Saharsa and Madhepura. In some of them, the limit was even lower at 30 children in the two categories.

So, it seems a tragedy—government-made and far bigger than the AES outbreak—is silently unfolding in the villages and urban settlements of Bihar.

The state already bears a terrible ignominy: it has the highest percentage of stunted (48.3 per cent) and underweight (43.9 per cent) children in the country, as per the National Family Health Survey-4 (2015-2016). This means almost half its kids are in the grip of acute malnutrition. So, it is no surprise that a study of 92 AES deaths from 2015 to 2017 by a team at Sri Krishna Medical College and Hospital, Muzaffarpur, found that the deceased were all malnourished.

In this backdrop, THE WEEK’s investigations reveal an appalling fact—about two-thirds of the children below six years are being deprived of supplementary nutrition. As stated on www.icdsbih.gov.in, the Bihar ICDS directorate has fixed the number of beneficiaries at 80 children (40 children each in the two age groups), eight pregnant and eight lactating women and three adolescent girls per anganwadi centre. This, irrespective of the number of eligible children and women in its jurisdiction. On ground, the number of beneficiaries further gets reduced.

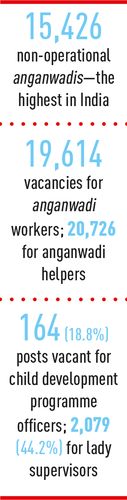

As per ICDS’s website, there are only 79.40 lakh beneficiaries at the 99,583 operational anganwadis. Deduct the number of pregnant women and adolescent girls—10.95 lakh—and only 68 lakh children benefit from the scheme. That is just about 36 per cent of 1.91 crore children below six years in the state (2011 census).

This, say experts, is a gross violation of not only the Supreme Court directives on universalisation of ICDS, issued between 2004 and 2006, but also the food security act, which guarantees the right to food and nutrition to all. “This is systemic exclusion of needy children that could be termed nutrition apartheid,” says activist Sachin Jain of Right to Food Campaign. “There is an immediate necessity for a social audit of child health and nutrition programmes in the state.”

Rupesh Kumar, former state adviser to Supreme Court commissioners in the Right to Food case, says, “Our work on ground and studies, too, reveal that only about 35 per cent children in Bihar are covered under ICDS, which is indicative of their nutrition condition. No wonder they are susceptible to diseases, including AES.”

Rina Devi Sahni of Mallah Tola in the same village would agree. Her sons, Prince, 7, and Chhotu, 2, died of AES on consecutive days. She has sent her three other children to her parents’ home. Her sons, too, did not go to the anganwadi or receive the rations. “It is quite far from our home, too,” she says.

Mohua Chatterjee, programme head of east India operations at CRY (Child Rights & You), says while the state has taken some positive steps, the ground reality is different in many districts. “The need of the hour is to reach out to the last child and ensure the right to food and nutrition is translated into reality, which means ensuring ICDS coverage for all children in every remote hamlet,” she says.

State authorities, however, deny that there was a cap on the number of beneficiaries. While social welfare minister Ramsewak Singh categorically says there is no such order, ICDS director Alok Kumar, in a reply to THE WEEK’s email, says, “ICDS services in Bihar have been universal since June 2014. To implement the National Food Security Act, 2013, ICDS Bihar had universalised its service to all through letter no. 3429 dated 19-06-2016.” As for the beneficiary figures on its website, he says “it is for budgetary provision”. “Some average number of beneficiaries has to be considered,” he says. “This is a moving average and the actual numbers at anganwadi centres could be different.” He did not explain why anganwadi workers adhered to the number fixed on the site.

Among the bigger states with poor health indices, Bihar is the only one where women and child development falls under the department of social welfare, showing a lack of focus on the sector. And Bihar’s ICDS directorate is headed, strangely, by an Indian Forest Service officer.

This lack of focus on women and child care translates into grim statistics. As per NFHS-4 data, only 34.3 per cent children received supplementary nutrition. As for growth monitoring, only 23 per cent of children were weighed at anganwadis. Every anganwadi is allotted Rs19,200 per month for supplementary nutrition, which is directly transferred to the account of workers. Some workers complain that they do not get the funds every month. There are allegations of corruption and payment of a “share” to higher officials. Moreover, Bihar’s contribution to the honorarium of anganwadi workers and helpers is the lowest among bigger states—Rs750 and Rs375, respectively—over the Central grant of Rs4,500 and Rs3,500. In Madhya Pradesh, the state share is Rs7,000 and Rs3,500, respectively.

According to a report of the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability, the budget outlay for direct nutrition interventions (DNIs) in Bihar for 2017-2018 was Rs2,687 crore—1.5 per cent of the budget. It was 1.9 per cent of the budget in 2014-2015. Also, the highest resource gap for DNIs was in the treatment of severe acute malnutrition cases. In 2017, only Rs8.9 crore was allotted against a requirement of Rs185 crore.

These gaps are manifested in the condition of children at Vaishali district’s Nutrition Rehabilitation Centre (NRC) at Mahua. When we reach there around 7pm, a frail Seema Devi, 18, looks crestfallen as she holds her seven-month-old daughter, Anupriya. Despite being admitted to the NRC a few days ago, the baby looks extremely malnourished. And, there is only Bina Devi, the cook, to take care of her and 14 other severely malnourished children. The 20-bed centre has only one feeding counsellor and a cook-cum-caretaker—the requirement is two each—and a medical social worker. The posts of two medical officers, eight nurses and two attendants lie vacant.

“It is very difficult. I will be on 24-hour duty today as the social worker is not present,” says Bina. She seems helpless, but so are the parents. “I want my child to be healthy, but she seems to be deteriorating by the day,” says Anupriya’s father, Ranjan Kumar. His voice is dejected, but it is haunting and resonates across Bihar’s most deprived districts. Only, the state seems to be deaf.