In August 2008, an unexpected judicial pronouncement was made at a fast-track court in Sitapur. It announced rigorous life imprisonment for 14 policemen for killing three young people in Sarsai village of Sitapur district. But it was hardly fast, for it had taken 27 years and 200 hearings for the judgment to be reached at the special court. Six of the policemen and nine of the witnesses had died by the time the judgment came.

The Sarsai judgement is almost an aberration in a state where 6,126 encounters have taken place since March 2017, when the present government came to power, in which 122 criminals have been killed and 13,361 put behind bars. Magisterial inquiries are mandatory in all encounter cases, and only 74 have been completed so far. In all 74, the action of the involved police personnel has been held correct.

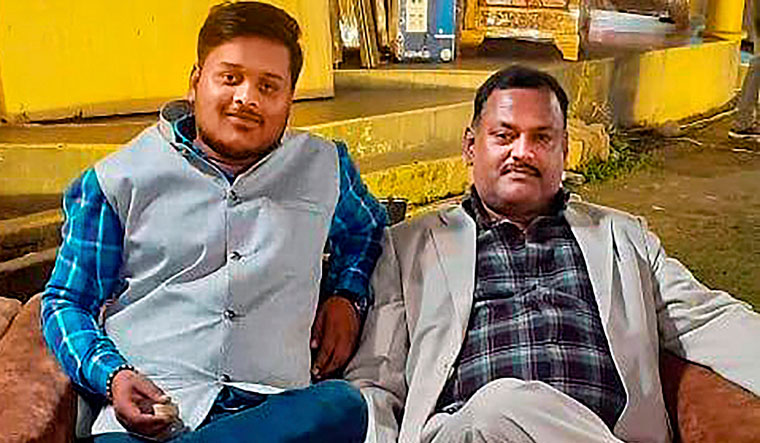

The Vikas Dubey encounter may be just another number, but it is proving to be a problematic one in a state where Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath has announced that criminals who shoot at the police should expect bullets in return. In its crudest form, this is labelled the thok do (shoot them) policy.

The Dubey encounter has raised many questions—the most important of which is why he would have attempted to escape when he surrendered of his own will in Ujjain. His surrender in a different state could have been prompted by the swift police action in nabbing and killing his associates while also razing his house in Kanpur.

Those doubts will now be investigated by two bodies. The first is a three-member Special Investigative Team (SIT) that will, among other things, look into the larger networks that had ensconced Dubey despite the 60 criminal cases against him. The composition of this body, experts say, is legally unsound as section 155(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure specifies: “Investigation includes all the proceedings under this Code for the collection of evidence conducted by a police officer or by any person (other than a magistrate) who is authorised by a magistrate in this behalf.” The SIT instead is headed by a bureaucrat. Of the other two members who are police officers, one is J. Ravinder Goud, who was charge-sheeted in a suspected case of fake encounter in 2007.

A one-man judicial commission headed by retired judge Shashi Kant Agarwal will look into the ambush at Bikaru, which left eight policemen dead on July 3, and the encounter on July 10, in which Dubey was killed while being ferried from Ujjain to Kanpur. Agarwal served at the Allahabad High Court between 1999 and 2005, after which he was transferred to Jharkhand.

Judicial commissions in the state anyway have little impact. Take, for instance, the one-man Nimesh Commission set up to probe the police version of the arrest of two alleged terrorists Khalid Mujahid and Tariq Qazmi responsible for the 2007 bomb blasts in Lucknow, Faizabad and Gorakhpur. The commission was formed in 2008 and its report tabled in the assembly in 2013. It called into question the police version of the arrests, but remained vague about pinning any responsibility.

Ram Das Nimesh, the author of that report told THE WEEK, “It is never in our hand to ensure what action the executive will take on a report”. The report, without any concrete findings, is believed to have earned him the chance to head yet another commission to look into the violence in Tappal, Aligarh, in 2010. This one, too, gave a clean chit to the local administration for the flare-up that left five dead.

Kumar Askand Pandey, associate professor of law, Dr Ram Manohar Lohia National Law University, Lucknow, said that most inquiry commissions are set up to fail. “Commissions and more commissions seem to be the norm in almost all cases which point to possible wrongdoing on the part of the police,” said Pandey. “All commissions work independently with no communication among them. Thus, larger issues always remain unaddressed. In the last three years, commissions in the state have been notorious for giving clean chits. The whole matter appears very murky.”

Vikram Singh, former director general of UP Police, said there seemed to be an ‘epidemic’ of questioning any action by the police. “I have no reason to disbelieve the version given by the UP STF (Special Task Force) and the UP Police based on my real-time exchange of fire with hazardous criminals,” said Singh. “Lame excuses are being given such as that he (Dubey) had a rod in his leg and thus could not have outrun the police…. The right to private defence by use of proportionate force is enshrined in the law and is established standard operation procedure.”

In 2013, Mujahid died while being ferried from a court in Faizabad to a Lucknow jail. An FIR was lodged by Mujahid’s uncle against 42 policemen and intelligence personnel, including Singh, who had by then retired and was more than 500km away in Haridwar when Mujahid died. “So many policemen languish in jails and die on such trumped up charges,” said Singh. “Not one armchair activist or any member of the candle-light gang sides with them.”

Another top cop, Brij Lal, who was then additional director general of police and later became the state’s DGP, was also named in the same FIR. Now retired and a BJP member, Lal, who is credited with bringing down 19 criminals through encounters, said: “Encounters have happened even before independence. Dreaded criminals do not yield themselves to easy arrests. They will fire till the last bullet. The police fire in retaliation.” Lal believes the police version but adds that the operation could have been better planned. “My first concern was always that the fewest number of people who needed to know about an operation should have knowledge of it,” he said.

A group of lawyers have written to the chief justice of the Allahabad High Court on July 11, asking him to take suo motu cognisance of the alleged extrajudicial killing of Dubey and order a “court-monitored CBI enquiry of the entire incident”. The letter raises 20 important queries related to the encounter.

Anurag Dixit, former vice president of the Central Bar Association, who co-wrote the letter, said that the state had sponsored a PIL against itself, a day later, to lend credence to its actions. “On July 12 (a Sunday) a hurriedly drafted PIL was filed before the Lucknow bench of the Allahabad High Court,” said Dixit. “This was immediately taken up on Monday and dismissed as it called for constituting a judicial commission headed by a former or sitting judge to probe the police encounter, a step which the government had already taken. The state thus has for itself a judicial nod for how it is going about to probe the matter. This also renders infructuous any other PILs in the matter till some fresh cause arises.”

For now, however, there are enough old questions to answer in one of the state’s most dramatic encounters.