His tribe harvests honey from tree hollows; they find the hive by following bees. Peddalu Mandli, 27, of Petralachenu in Telangana is slowly learning that art from elders. Last week, Mandli and a few others tracked down a hive. “Only our tribe has the expertise to find these beehives and collect honey from it,” he says proudly.

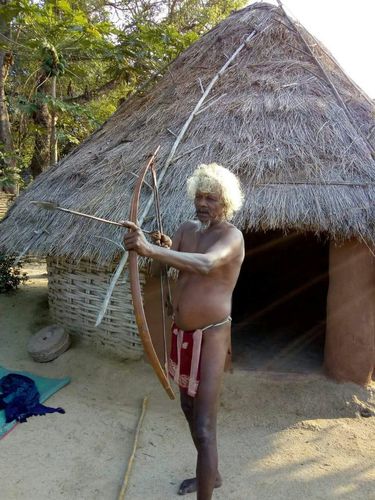

Mandli hails from the Chenchu tribe, one of the oldest aboriginal tribes in India. Hunter-gatherers, the Chenchus live in the thickly forested Nallamala Hills—around 9,000sqkm in the Eastern Ghats, spread across Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. The tribe also has a presence in Karnataka and Odisha.

Unlike most other members of his tribe, Mandli has lived in a city and has a degree—a bachelor’s in education. For some time, he waited tables in Hyderabad. But now, to protect himself and his tribe, he has moved back to the hamlet and its traditional way of life. Wary of Covid-19, Petralachenu residents—around 200 people—have cut ties with the outside world.

As the men are excellent marksmen, hunting expeditions have been stepped up during the lockdown; the bag mostly yields birds and small animals. “I am not that good with the bow,” says Mandli. “So, I take along my dog, who plays a major role in our hunting trips. We have realised that if we have to survive the pandemic, we have to go back to our traditional lifestyle. In future, I want to cultivate and promote the crops that our elders used to eat; it will keep us healthy and immune.”

The Chenchu hamlets are called pentas. While an exact number of pentas is not available, there are reportedly 48,000 Chenchus on record. Many of the pentas are situated close to Nagarjunasagar-Srisailam Tiger Reserve, India’s largest tiger reserve. The tiger is the tribe’s totem. They believe that whenever they are on the verge of starvation, a tiger will come to their rescue and leave a dead prey for them to feast on.

Dharmakari Ramkishan, a government doctor and an activist who has studied the Chenchus extensively, says that Covid-19 could wipe out the tribe. “Chenchu are officially categorised under particularly vulnerable tribal groups,” he says. “Since they have lived in deep forests all their lives, they have not been exposed to major infections. Their immunity to Covid-19 will be much lesser than people from other communities.”

Ramkishan, who also runs an NGO called Chenchu Lokam, adds that the tribe’s mortality rate is thrice the national average. “From an anthropological point of view, they are walking historical treasures,” he says. “Studying them can reveal a wealth of information. The state government should immediately announce a separate Chenchu plan and make sure that their immunity levels are improved.”

As of now, not a single Covid-19 case has been registered in any of the pentas, probably because most hamlets are far off the beaten track. Hamlets in the Appapur Gudem area, for example, are 35km off a motorable road.

“We have warned forest officials not to enter our region, because we want to rule out every possibility of contracting infection,” says T. Balaguruvaiah, sarpanch of the Appapur cluster. “We told the officials and other outsiders who wanted to provide us with food that we can survive as well as take care of the forest on our own. My priority is to ensure that my tribe does not get wiped out.” The tribal elders have nominated one tribesman to manage the government-run Girijan Cooperative Corporation outlet in the forest from where rice and essentials are procured every month.

Government officials, too, are doing their best to ensure that the tribe has limited contact with outsiders. T. Akhilesh Reddy, project officer of the Telangana government’s integrated tribal development agency, says: “We have completely restricted access to Chenchu habitats. But despite our warning some politicians and NGOs are trying to contact them. From our side, we have supplied them with rations to last a good amount of time and are also ensuring (supply of) essential items and water.”

Meanwhile, the tribe has its own strategy in place, in case anybody tests positive for Covid-19. “We believe that a drink made from a powerful herb called naleni found only in the forests can be effective against this virus,” says Balaguruvaiah. “Our ancestors used to drink it (to ward off) malaria. Along with this drink, we are also looking at other medicinal herbs to fight this virus. Since good hospitals are far, we have to be prepared.”