The arrival of spring usually brings cheer to Kashmir, as business and tourism pick up pace after the winter gloom. This year, though, the season has hundreds of hoteliers, traders and shop-owners worried. The reason is the Jammu and Kashmir government’s Land Grant Rules, 2022, which says all commercial leases granted by the government as per older rules “shall not be renewed”. The new rules are, in essence, an eviction notice to businesses operating from buildings constructed on land leased from the government.

The government intends to form a committee to assess if the leaseholders have violated terms. It will also compensate those who have made “improvements”, including constructing a structure on the leased land. The new rules say all parcels of land whose leases expire, or have already expired, would be e-auctioned and used for infrastructure development, including “housing for ex-servicemen, war widows, families of deprived categories [and] migrant workers”, and for “any other purpose in the interest of Jammu and Kashmir”.

Traders fear that the new rules will put hundreds of people out of business and radically alter the stake-holding of local people in all forms of commercial activity. They say similar auctions in recent times have given outsiders the upper hand in minerals and liquor businesses.

An official of the Kashmir Traders and Manufacturers Federation (KTMF) said the new rules would impact nearly half the businesses in Srinagar, including 2,000 small and medium businesses in the 1.8km stretch from Hari Singh Street to Polo View that serves as Kashmir’s commercial hub. “Some businesses have been operating from leased land for more than 70 years, or even before the partition,” he said. “What will happen to them if the new rules take effect?”

A shopkeeper at Residency Road in Srinagar said the new rules affected livelihoods. “I purchased this small shop (140sqft) in 2002 after making a goodwill payment to the landlord,” said the shopkeeper. “[The landlord’s] lease had expired, but the rules then allowed renewal of expired leases. The deal was registered in the court without any hassle.”

Inder Kishen | Tariq Bhat

Inder Kishen | Tariq Bhat

Ghulam Sarwar, owner of Kashmir Book Shop in Srinagar, said he had struck a similar deal. “I also paid the landlord, because the rules then allowed renewal of expired leases,” said Sarwar.

Khursheed Bhat owns a fabric store in Fair Deal Shopping Complex, a 35,000-sqft building housing 70 shops. According to Bhat, part of the shopping complex was built on nazool land, or state land, 28 years ago. Some of the shops in the complex, he said, had received notices from the government. “We have been telling the government for the past 14 years that the lease granted to this complex had expired. Tell us what we have to do,” said Bhat.

He said businesses built on nazool land became illegal occupants of government land after the J&K State Lands (Vesting of Ownership to the Occupants) Act, 2001, was scrapped in December 2021. The act had allowed those who occupied nazool land before January 1, 1990, to secure ownership rights by paying a premium. The scheme was launched by the government to raise money to fund power projects. The target was Rs25,000 crore, but the government could raise just Rs75 crore because ownership rights were granted for free after the act was amended in 2004 and 2006.

Declaring the act as “null and void” in 2020, governor Satya Pal Malik ordered that land regularised under the act be retrieved in six months and encroachments removed. The order came weeks after the J&K and Ladakh High Court ordered a CBI investigation into the allegation that the act had resulted in a Rs25,000 crore land scam.

Farhan Kitab | Tariq Bhat

Farhan Kitab | Tariq Bhat

Inder Kishen, a Kashmiri Pandit who owns a stationery store at Polo View, fears that he would lose the business that his family had run for generations. “My grandfather Baljee Kundu started this business before the partition. It is our bread and butter,” said Kishen.

Farhan Kitab, president of the Residency Road Shopkeepers’ Association, said leaseholders had sublet their property to businesses decades ago. “Business has suffered because of the situation in Kashmir and calamities like the 2014 floods; now these rules have come as another setback,” said Kitab. “Our appeal is that the government should either give us ownership rights against a premium―since we have already made goodwill payments for setting up our businesses―or [an opportunity to] enter into an agreement. Else, families will suffer and big land-grabbers could exploit the situation.”

He said the association met Lt Governor Manoj Sinha and senior government officials after the new rules came into effect. After the meeting, said Kitab, Sinha said small businesses would not be touched.

Hoteliers are especially worried. Hotels in Gulmarg, Pahalgam and Udhampur and on Boulevard Road along Dal Lake will be up for grabs if the government decides to ignore their pleas. All hotels in Gulmarg, except for the five-star Khyber Resort, have lapsed leases. Mushtaq Chaya, owner of a chain of hotels in and outside Kashmir, said a delegation of hoteliers led by him discussed the issue with Sinha. “Of the initial 40-year lease period, there was no business for 30 years because of militancy,” said Chaya.

Several hoteliers in Gulmarg said they were witnessing impressive footfalls for the first time since the pandemic. “The government should renew the lease of hotels without delay,” said Imran Nazir, general manager of Heevan Retreat. “At a time when unemployment in Kashmir, at 21 per cent, is the highest in the country, each hotel employs hundreds of people directly and indirectly. Even a day’s disruption will have a serious impact on the industry.”

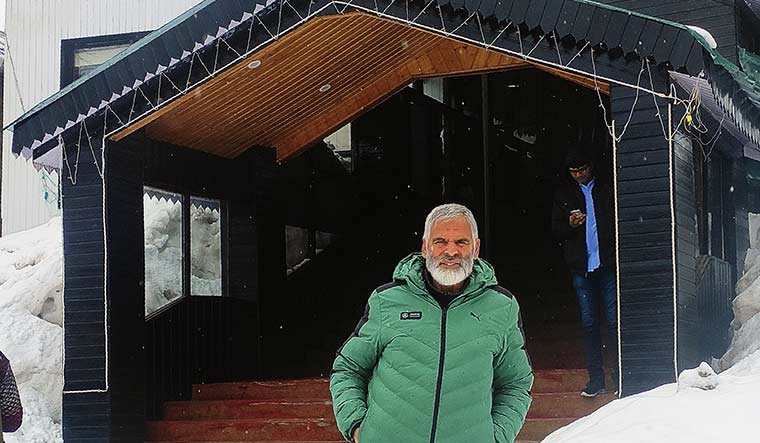

Imran Nazir | Tariq Bhat

Imran Nazir | Tariq Bhat

According to Nazir, the number of affluent tourists visiting Kashmir has gone up for the first time in 30 years. “It started because of Covid, as people who couldn’t travel abroad for holidays turned to Kashmir,” he said. “They found the place more scenic, and affordable, than locations abroad. In a way, Covid was a blessing in disguise. Those who visited during the pandemic are making repeat trips and bringing friends and relatives along.”

Ghulam Muhammad Malik, manager at the three-star Alpine Ridge, Gulmarg, said the property’s lease had lapsed in September 2019. “This hotel was built in 2013,” he said. “We have invested in this business [expecting] a 90-year lease. Hotel maintenance expenses in Gulmarg are very high because of heavy snowfall.” The government, he said, must consider the difficulties they have overcome in the past few decades.

The new rules may also affect the functioning of several schools in Kashmir. “The rules will impact nearly 650 schools, including Christian missionary schools,” said G.N. Var, head of the private schools association in Srinagar. Four prominent schools in Srinagar―Tyndale Biscoe and Mallinson Girls at Sheikh Bagh, Burn Hall at Sonwar, and Presentation Convent at Rajbagh―had leases that expired before 2000. Burn Hall and Presentation Convent renewed their leases three months before Article 370 was voided.

In April last year, the government asked all private schools to furnish details regarding their lapsed leases. As many as 400 schools that had renewed their registration faced the threat of closure. The government action, however, was stayed by the court and criticised by political parties. “The leases have expired, but people should get a chance for renewal,” said former chief minister Omar Abdullah. “Fix the rate and tell people to pay.”

Altaf Bukhari of J&K Apni Party said the new rules were draconian and inhuman. “If the government did not extend the leases, it is not the leaseholders’ mistake. [The new rules] cannot stand the scrutiny of law,” he said.

According to Peoples Conference leader Sajad Lone, the new rules have a sinister objective. “They are not without motives,” he said. “It may start the dark chapter of blatantly othering the Kashmiris.”