Few people leave a meeting with Oommen Chandy without having an anecdote burnt into their memory. I, too, had the privilege of going through the experience.

It was April 2016―perhaps the cruellest month in Chandy’s long career. He was into his last weeks as chief minister, and his government was wracked by scandals and allegations of corruption. Chandy was popular as ever, but the faction-ridden Congress and its fickle allies were hindering his reelection bid.

On April 10, there was a bolt from the blue: fireworks stored at a temple festival at Puttingal blew up, killing more than 100 people and injuring 400. Chandy was at the other end of the state in Kasaragod, Kerala’s northernmost district.

He took an evening train out of Kasaragod, and arrived just in time for the emergency morning meeting at the government medical college in Thiruvananthapuram. Most of the injured were being treated there, and Chandy personally interacted with many of them.

His official car, a well-used Toyota Innova, was waiting outside to take him to Puthupally, his hometown and assembly constituency in Kottayam district. I was in the car for a pre-arranged interview. After letting me in, his aides had asked me to sit right behind the driver. “Be ready for his entry,” they said. “There is always a commotion, but today is going to be tough.”

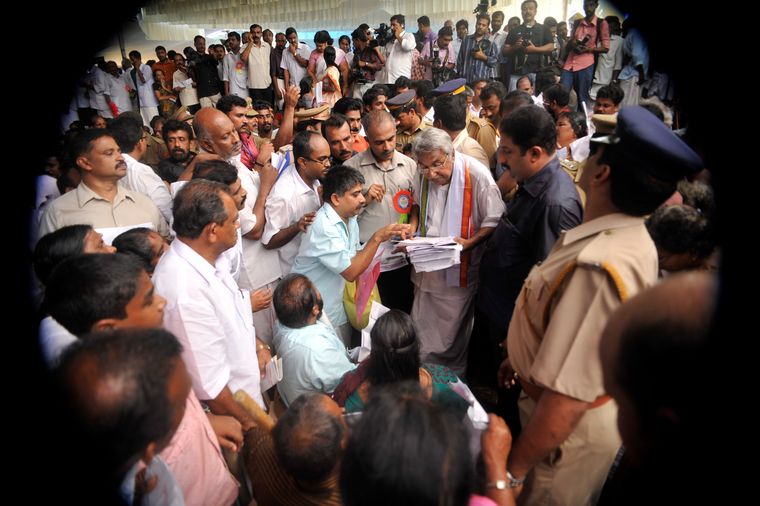

They were right. A buzzing swarm of policemen, party workers, journalists and hospital staff blew out of the building, and at its centre was a solemn-faced Chandy. Amid the jostle to approach the car, he kept on patiently answering questions from reporters. The overnight train journey must have been exhausting, but Chandy looked oddly energised by the commotion.

The four-hour journey to Puthupally involved several detours. Between taking calls, poring over files and answering my queries, Chandy would get out of the car at regular intervals and address poll rallies. Each halt involved a wave of excited party workers sweeping the chief minister off his feet and pushing him to the podium, and then depositing him back into the car after the speech. Mao Zedong had once said that a politician’s job is to move among people as a fish swims in the sea. Chandy was doing it.

With each rally, though, his white khadi shirt became a little more crumpled, and his famously tousled hair a little more dishevelled.

A large package awaited the car at Kottarakkara, home to the famous Sri Maha Ganapati Temple. An aide took delivery and winked at me as he opened it. “Now, please don’t write about this,” he warned, as he offered me one of the choicest nivedhyams one could have from a Kerala temple. It was the Kottarakkara unniappam, a rice cake made of ghee, jaggery, banana and spices―first made centuries ago by the legendary master builder Perumthachan, whose work shaped much of Kerala’s architectural sensibilities.

“Whenever the CM is in town, the unniappams come,” said the aide.

Chandy, though, declined to have one when he returned. He was apparently still soaking in the sweet sea of adulation. The unniappams could wait.

IT IS IRONIC that Chandy’s entry into politics owed much to the fact that he stood out from the crowd at the right time.

In 1957, when Chandy was a class 8 student, Congress firebrand M.A. John visited Puthupally to meet a prospective recruit―the student leader of the school that Chandy’s grandfather had built. It was a Sunday evening, and the school was closed. No one seemed to know where the boy was. Someone told John that a lanky lad on the roadside could be of help.

The lad, John would later recollect, was wearing an overlong blue shirt that made it look like there was nothing underneath. “I asked him whether he could help me, and he agreed,” wrote John in his autobiography. “We struck up a conversation as we walked, and I learnt that his grandfather was a member of the Travancore legislative assembly as well as the manager of the school. The boy was Oommen Chandy.”

John had the subversive thought of inviting Chandy to a planned student protest. “He came to my office the next day, and I added his name in the list of people who would join the picket line,” wrote John. “Those days, arrested students would get jail time of two-three weeks. Chandy got two.”

Soon after his release, Chandy joined the Congress-affiliated Kerala Students’ Union. Students in Kerala were an electorally unrepresented community, and KSU was founded to protect their interests. The communists, who had come to power in Kerala on the back of peasant movements and trade unions, initially neglected student politics. There were bigger fish to catch than from the narrow pool of 40,000 voting-age students.

KSU started filling the void with small, surefooted steps. It formed a network of student leaders, printed pamphlets and organised impromptu strikes to work up a momentum. Within a decade, the strategy spawned KSU units in most of the 82 colleges in the state and a crop of idealistic leaders such as Vayalar Ravi and A.K. Antony emerged.

Chandy became KSU general secretary in 1964 and president in 1967. The crucible of student politics had by then become unusually hot. A police crackdown in Kochi had resulted in a pre-degree student falling into a ditch and later succumbing to his injuries.

It was time for a statewide showdown. As many as 130 elected college union leaders from 82 colleges met in Kochi and elected Chandy to be the convener of a prolonged agitation. As the left government under chief minister E.M.S. Namboodiripad threw its weight behind the police, violent clashes broke out in several districts. A slanging match between Chandy and Namboodiripad elevated not just the tensions, but Chandy’s stature as well. With public opinion beginning to turn against the government, the chief minister finally extended an olive branch on the 25th day of the agitation.

It was Chandy’s first big political victory.

He followed it up with his own olive branch. In 1968, when the state was facing acute food shortage, KSU drafted a nine-point plan that called for the formation of farmers’ clubs in schools and colleges, the distribution of seeds and manure, and government support for selling the produce.

The plan was submitted to M.N. Govindan Nair, agriculture minister and communist stalwart. Nair was mighty pleased. He released two lakh seed packets, of which 70,000 went to KSU. M.K.K. Nair, the legendary managing director of the fertiliser company FACT, gave manure free of cost. The minister sowed the first paddy seeds at a field in Kunnamkulam, as Chandy, Antony and other Congress leaders looked on.

The Congress had won just 9 of 133 assembly seats in Kerala the year Chandy became KSU president. In the next three years, KSU under him helped the party not just turn around its fortunes, but build a coalition government that became the first to complete a full term.

IN TACTICS, Chandy’s greatest frenemy in the party was K. Karunakaran, a trade union leader who went on to become the party’s longest serving chief minister. Much like Karunakaran, Chandy knew the importance of trade unions and cooperatives in electoral politics. Even as they fought wider political battles, Chandy’s organisational skills and negotiating abilities earned Karunakaran’s grudging respect.

Jos Dominic, managing director and CEO of the hospitality brand CGH Earth, recalled how Chandy negotiated the choppy union waters. “In 1972, we started Anjali Hotel in Kottayam, and Chandy became the president of the employees union,” he said. “He was dealing with my father at the time, and I still remember my father exclaiming, ‘Is this trade unionism? There are hardly any problems. Everything’s so fair, the discussions are so easy, and there is no bitterness.’ I think Chandy’s tact in dealing with the contrarian view was just remarkable.”

That tact held him in good stead throughout the tumultuous political changes in the 1980s and the 1990s. The decades made him the commanding general of the ‘A’ faction in the Congress―so named after its leader, Antony. Their bond from the KSU days was so strong that, even though Chandy was an avowed anti-communist, he followed Antony into the left camp after the Congress split in 1980. The political experiment ultimately failed, but Chandy remained a staunch Antony loyalist.

The ‘A’ group subsequently merged with the Karunakaran-led ‘I’ group, leading to rich electoral dividends and two decades of fierce faction fights. The merger also birthed a lasting template in Kerala politics―a bipolar polity dominated by the Congress-led United Democratic Front and the CPI(M)-led Left Democratic Front. The UDF and the LDF alternately ruled Kerala for the next 40 years, until the latter retained power in the 2021 polls.

“Chandy did not confine himself to theoretical complexities in his approach,” said Panakkad Sayyid Sadiq Ali Shihab Thangal, state president of the Indian Union Muslim League, the Congress’s most prominent ally in the UDF. “His remarkable abilities in both thought and action, particularly his efforts to establish a strong connect between the UDF and the people, deserve special mention.”

It was in 2004, after he succeeded Antony as chief minister, that Chandy truly came into his own as the most popular face of the Congress. His mass contact programme set an example for other chief ministers, and his focus on bringing speedy and sustainable development to the state inspired many experts to lend a hand.

“I first met Chandy in Delhi in 2011, just after he became chief minister [for the second time],” said E. Sreedharan, former head of the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation. “‘Are you retiring this year?’ he asked me. I said I was. He said, ‘Sreedharan, you have done a lot of work for many states, but not for Kerala. So, if you are retiring, you must come back to Kerala and take charge of the construction of Kochi Metro.’”

Chandy ensured that construction of the metro began with Sreedharan in charge. By the time his tenure ended in 2016, Chandy had also flagged off a slew of development projects that would change the face of the state.

His strongest suit, however, remained his view of governance as a pay-it-forward game. In the 1970s, when he became minister for the first time, Chandy was assigned the task of guiding a young Haryana minister who was visiting Thiruvananthapuram to study a first-of-its-kind slum rehabilitation project his department had undertaken. For Chandy, the assignment came at a most inconvenient time―his first child was on her way, and he wanted to be with his wife, Mariyamma, when the moment came. But not one to neglect the call of duty, Chandy first played host to the Haryana minister before hurrying to the hospital.

Decades later, when the civil war in Iraq was raging, chief minister Chandy sent a plane to rescue 42 Malayali nurses trapped in Baghdad. But the mission ran into trouble. “The plane was barred permission to land in Iraq and the pilot was about to return,” Chandy recalled. “I was stunned. I did not know whom to turn to for help.”

Luckily, the external affairs minister happened to be Sushma Swaraj, to whom Chandy had patiently explained the slum project the day he became a father. One phone call, and Swaraj took up the matter and began pulling strings.

“It was because of her help,” Chandy said in 2019, when Swaraj died, “that we could save those 42 angels and bring them back to Kerala’s soil.”

Now, with Chandy gone, Kerala’s soil has lost an angel.

With Nirmal Jovial