A man said to the universe:

“Sir, I exist!”

“However,” replied the universe,

“The fact has not created in me

A sense of obligation.”

Stephen Crane

The universe, as climate change shows us, does not care how long we live or we don’t. Our lifespan and healthspan are entirely up to us, both collectively as well as individually. Let us start by understanding the difference between healthspan and lifespan.

Lifespan

We live longer than ever before. Despite Covid-19, this decade is the healthiest we have ever been, in virtually every country in this world.

In 1809, the population of the world was around 1 billion, with a fertility rate of between 4.5 and 6.2, and a child mortality rate of around 50 per cent, which ensured that the population remained static/stable at that number with births and deaths pretty much canceling each other out. Today, in 2024, we are 8 billion people, with a global infant mortality rate down to 2.9 per cent with just 4.6 per cent of these children dying before the age of 15. Despite our perceptions, and notwithstanding the Covid-19 pandemic, life expectancy and virtually all other health parameters have markedly improved globally as compared to just up to 200 years ago.

This is amazing progress. For over 30,000 years, human health pretty much mirrored the situation in 1809 with high fertility, high child mortality and an average lifespan between 20 to 40 years. And then, within a short span of just 200 years, everything changed. Despite the significant global discrepancies and inequalities due to geographical, environmental and income-related differences, even the poorest of poor countries are better off than just 100 years ago.

How did this happen? What dramatic changes altered the health landscape?

Most people tend to attribute increased lifespan to the advent of modern medicine and improvements in technology like robotic surgery, CT scans and expensive medicines. However, the real reason for increased longevity is socio-economic and political; reduction in poverty, better education, clean water, better sanitation, adequate nutrition, immunisation and the use of antibiotics. If we look at a pyramid of effectiveness, improved socio-economic factors at the base have the biggest impact, followed by laws (smoking bans, seatbelts, etc.), followed by protective interventions such as vaccines and preventive methods such as the use of statins and mammography and the early diagnosis of diabetes and hypertension and then comes treatment by doctors and hospitals at the apex of the pyramid, having the least impact on the longevity of the population at large.

This is not to say that doctors and hospitals are of no use. They are, but they are important when we fall sick, whereas the measures we take to prevent ourselves from becoming ill in the first place are far more critical, and this onus is on us.

Healthspan

There is a current upper limit to our lives despite our increased lifespans. Very few people in India make it to above 80 and a minuscule number makes it to above 90. There is an exponential death rate after the age of 65, which is why, as we age, we keep seeing people around us dropping off faster and faster.

Moreover, the longer we live, the more is the morbidity associated with chronic diseases that afflicts those of us above the age of 50. We live longer but many of us suffer through this longer life.

What is therefore more important than just the lifespan is the healthspan, which is the time period lived until a major disease, such as stroke, heart attack or cancer affects us, and leads to a life lived with disability and suffering until the end of our lifespan.

Effectively, the longer we live, the more is the chance that we will live with disease and disability. This is the Faustian bargain we have made by significantly reducing childhood mortality and adding years to our lives. We live longer, but with disease.

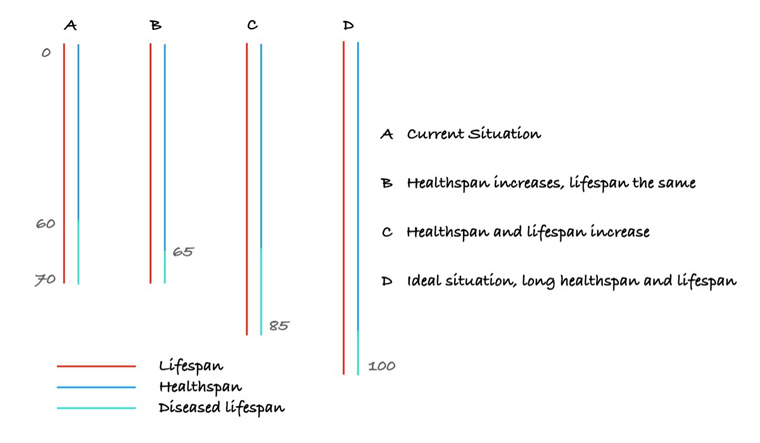

In India, as the diagram shows, our average lifespan is almost 70 years. However, the current healthspan is just 60 years, by which time half of us who have managed to reach the age of 60 will have at least one or more chronic diseases with some disability/morbidity.

If however, our healthspan were to go up to 65 years (scenario B), without a change in the lifespan, we would live a shorter diseased life of just 5 years. If the lifespan were also to increase, which is likely to happen in the years to come (scenario C) then we will live longer, but the period lived with disease will also increase.

The trick, therefore, is to increase our healthspan and lifespan both, but healthspan relatively more, so that we reduce the number of years with disease to as less as possible, as I have shown in scenario D, where if we could increase our lifespan to 100 years and healthspan to 90 or 95 years, we could compress our years of disease before death to a very short period of time of just 5-10 years.

Many of us currently touching 60 years of age, will statistically live another 1,500 odd weeks till the age of 90. This means we need to do everything we can to ensure we live a long healthspan of at least 1300 weeks to enjoy our remaining lifespan.

The aim of this weekly column is to discuss the various points that help us live long, healthy, to have a long healthspan within a long lifespan.

This is my 15-point guide that I will elaborate further upon in the weeks to come.

1. Move - be physically active - daily

2. Eat less, eat smart - eat sensibly - daily

3. Sleep well - daily

4. Calm your mind and build cognitive reserves - daily (meditation, downtime, learning, reading)

5. Manage your medications, supplements, vaccines - daily, once in six months, yearly, one time

6. Moderate your addictions and stimulants (smoking, gutka, alcohol, caffeine, marijuana) - daily

7. Do not fall (improve balance, take care not to fall) - daily and assess frailty - yearly

8. Manage your senses (oral, vision, hearing) - daily, yearly

9. Address abnormal environmental exposures (your exposome) and stressors at a personal level (air pollution, noise pollution, extremes of temperature, digital noise, accidents - intended and unintended, management of incidental findings when asymptomatic) - daily, one time

10. Be aware of your weight - monthly and log calories for 4-5 days in a month - monthly

11. Manage your cardiovascular risk yourself - quarterly, yearly

12. Screen for cancers and diseases, where screening actually makes a difference - yearly, biennially, every 5 years

13. Get/renew good health insurance - yearly

14. Identify doctors and health systems around you and work out the associated health and disease logistics in advance - one time

15. Take stock of the remaining 1500 weeks of your life (between ages 60 and 90) - yearly

One day we may even be able to add two more lines to Stephen Crane’s poem,

“That may be fine sir”, the man retorted,

But I may no longer need anything from you.”