The scorching sun blinds the eyes and depletes me of the little energy I have remaining. I quit complaining as I realise it's just the start of the week. To add to this, the flashing news headline steals my attention. A water crisis in Delhi is flooding the internet with questions being asked about who is responsible for this calamity. As I witness yet another humanitarian crisis turn into a political controversy, I cannot help but think of the catastrophic damage that human beings have caused to the planet and its resources.

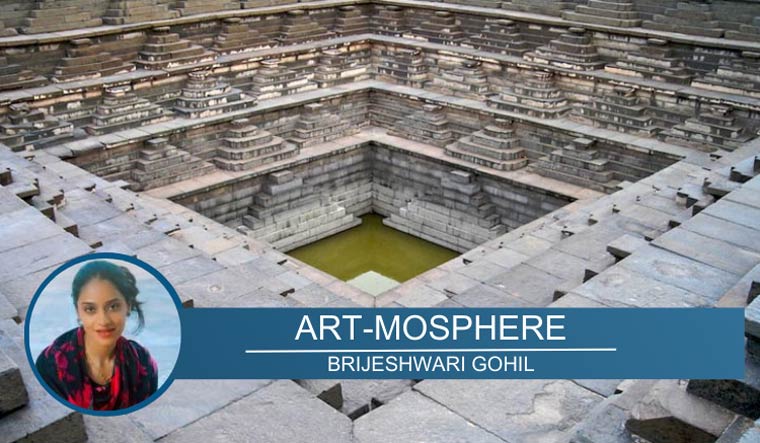

This is what has led to the scorching heat, water shortage and overall climate change. Historic, architectural marvels, such as stepwells, were built across western India to deal with weather fluctuations, droughts and deluges. Similarly, kuhls were created in northern India to allow glacial water to reach the remotest of villages. At a time when the nation, especially our metro cities, face water shortages, perhaps restoring and reviving these traditional water conservation systems could be of utmost importance?

So far, a few popular stepwells in India have been spotlighted as tourist destinations. Usually these are given importance for their architectural beauty, exquisite craftsmanship or the sentiment with which they were built. Rani ki Vav in Patan (Gujarat), for example, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, inviting several visitors daily. The monument is believed to have been built by Queen Udayamati in memory of her husband Bhima I. Once submerged by the River Saraswati, Rani Ki Vav was excavated only in the 1980s and took over seven years to be restored.

Stepwells served an important purpose and few people have bothered to understand the science and engineering of these historic monuments. The water collected was used for drinking, irrigation, agricultural purposes, religious rituals and practices. It was also these sites that served as places of community bonding. If revived, these could be hugely beneficial. The Rajasthan government has been working for the past five years on reviving traditional water systems under the Mukhyamantri Jal Swavalamban Abhiyan for this precise purpose.

In my hometown Bhavnagar too, a drought-prone region of Gujarat, local organisations are attempting to do this. I recently had the opportunity to be part of one such project where stepwells between two towns in the Bhavnagar district were documented. Since none of these stepwells are attractive or of elaborate design, they were neglected and never caught the eye of town planners and developers. Over the years they were covered by soil and were not in any working condition. When the water shortage became an alarming crisis, local villagers decided to take up the task of opening these heritage structures and utilising them for the purpose they were built to serve. Perhaps they were inspired by the conservation work at Kishan Kund in Alwar (Rajasthan) or Toorji Stepwell in Jodhpur (Rajasthan). Both of which are success stories where the revival of the stepwells has turned out to be a blessing for the locals. Even the World Monument Fund, India, is attempting to take on a similar task in stepwells of Rajasthan and Gujarat.

Rightly so, as these inverted monuments, stone cisterns have the power to combat our water crisis. However, restoration is not cheap or easy. Furthermore, unplanned development and damage to the soil are leading to a severe decline in the water table. If this continues to occur at an unprecedented rate, the hope for stepwells as water saviours may also be bleak.

A vast number of resources go into the revival of a stepwell. This includes but is not limited to recharging the groundwater and cleaning out the toxins and waste, clearing up clogged channels and at times creating new channels, which would ultimately help water reach the villages. Restoring the structure includes sandblasting the stone and brick in order to clean it. Strengthening the structure in the right manner is integral so that it can successfully house clean water.

Given the sheer growing population of the country and it being the largest user of groundwater in the world, government and corporate CSR donors need to start utilising their financial resources to restore these functional heritage monuments. While several private and not-for-profit organisations are attempting to do this, with the hope of serving the community. Once revived, there is also the responsibility of maintaining them. Keeping the stepwells clean and protecting them from being vandalised would require heritage sensitisation amongst the local community.

While heritage tourism is beneficial for a local economy financially, heritage conservation of cultural and natural heritage sites like this can serve the local population with basic needs. Perhaps if we give the political controversies a rest and focus on reviving traditional water systems, historic technological advances can safeguard our present-day crisis.

Restoring India’s historic stepwells, a solution to the water crisis

A few popular stepwells in India have been spotlighted as tourist destinations

Photo credit: Dharani Prakash (via Commons)

Photo credit: Dharani Prakash (via Commons)