The fascination with the east is apparent for millennia, from the time of the Silk Roads. The journey grew in leaps and bounds with better connectivity and a deep interconnectedness of communities. In more recent times, the Orientalists travelled the length and breadth of the east, writing and painting along their journey. These traveller accounts became important historical narratives and the cultural exchanges are an interesting way to understand and unravel global heritage.

The year 2024 has seen museums and historic institutions of the west tap into their collections as well as borrow works from other institutions to celebrate cultural crossovers and bring communities together. The east remains a topic of fascination and intrigue.

The Wallace Collection in London recently concluded a six-month long exhibition titled, ‘Ranjit Singh: Sikh, Warrior, King’. The exhibition explored the life of the Sikh leader Maharaja Ranjit Singh whose conquests and leadership led to a flourishing empire. Almost hundred works of art from 1780 till 1839, bring to life and are testimony of the great, highly influential Sikh Empire. His ornate, decorative sword for example, gold mounted and detailed with pearls and rubies was one of the striking artefacts on display. While attributed to have been made in Lucknow, it is interesting to see the Damascus steel sword now placed at an exhibition in the United Kingdom. Objects travel near and far, shedding light on people, politics, and culture of a bygone era.

The sheer sea of humanity coming to witness this exhibition is not only testimony to the interest in the Maharaja who was a hero for many Sikhs but also an indication to the continuing interest in the east.

Parallel to the Ranjit Singh exhibition, ‘Silk Roads’ at the British Museum takes you back in time to AD500 to 1000 where overlapping networks from East Asia to Britain and Scandinavia to Madagascar connected communities across continents. The exhibition, which is on display till February 2025 is a thought-provoking show to understand the rise of universal religions and the trade networks that contributed to art, design, culture, community.

The exhibition also makes one rethink the period which from a western context is popularly known as the Dark Ages. The web of routes that connected people and goods across land and sea, led to the flourishing of new ideas, artistic styles and technological advancements. In which case, was it really the dark ages?

A wooden panel, from a Buddhist shrine in Khotan, describes the legend of the Chinese princess who smuggled the secret of how silk was made in her elaborate headdress. She concealed cocoons of silk as well as seeds of the mulberry tree across the border to her marital home in Khotan. With this knowledge and technology, production of silk travelled from China via the Silk Road to Byzantium and further to northern Europe. If it was not for objects such as these, our knowledge on the past would be limited with many gaps and uncertainties.

To solidify research and successfully present elaborate exhibitions such as these, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum launched the Asian Art Initiative in 2006. Dedicated to integrating Asian art into its larger collection and education programme, the initiative has led to exemplary exhibitions, retrospectives and acquisitions.

Landmark exhibitions such as Silk Roads as well as ‘Asian Bronze: 4000 Years of Beauty’ at Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam are great examples of how museums of the west are evaluating their collections as well as rethinking global art history. Asian Bronze explores the connectivity within Asia through centuries, examining beautiful bronze works of art. One of the many artefacts displayed at the exhibitions which is open until 12th January 2025, is a bronze work of Buddha under Naga’s hood from the National Museum, Bangkok, Thailand. The object is an example of exquisite craftsmanship and intricate detailing.

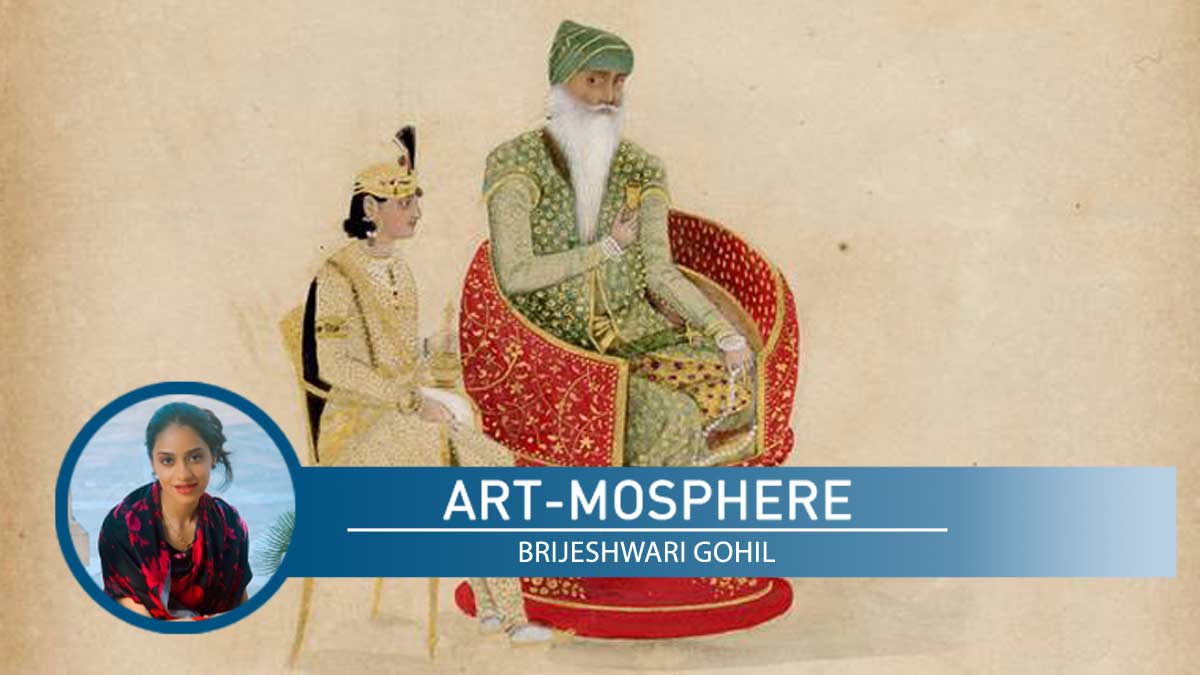

This week, a new exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London commences on the Mughals. ‘The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture and Opulence’, celebrates the contributions of the Mughal Empire during its golden period from 1560 to 1660, during the reign of Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan. A time when patronage was at its prime and ornate, opulent art and architecture was commissioned.

England's earliest official encounters with India have been documented in 1616 by the first ambassador to the Mughal Court, Sir Thomas Roe. In a letter, Roe writes about Emperor Jehangir's kingdom being a treasury of the world. The exhibition celebrates the culture of cosmopolitanism that prevailed, the rational discourse, religious diversity, scholarly enquiry and intellectual tolerance which was encouraged. These artefacts are a symbol of the aesthetic achievements of a great empire.

Amongst the many captivating objects, artefacts, textiles presented is an exquisite hunting coat embroidered with satin and silk. The embroidery termed as fine ‘chain stitch’ was done by male embroiderers of Gujarat who were patronised by the Mughal court to create garments for not just royalty and aristocracy but also to be exported to the west. Narratives such as these help in understanding colonial influences as well as the socio-political relations of the time.

Cultural exchange and global travel are far easier now. Museums have understood the power of art in bringing together communities and building networks. Today, people are visiting these storehouses of wealth from across the globe to understand world history and the cultural exchanges that took place. The fascination for the exotic east prevails.