Diabetes in India is treated like a garrulous, old, family friend; bothersome, but mostly familiar and harmless. The seriousness of the condition is undermined by its ubiquitous nature. Ritwik Pradeep (name changed), 38, felt the same way about the disease. Diagnosed with diabetes at age 27, he paid little heed to his lifestyle, despite both his parents suffering from, and eventually succumbing to, the effects of the disease; his father had a heart attack and died of complications of a bypass surgery, and his mother died of stroke in her 40s. A senior executive in a company in Mumbai, Ritwik worked long hours and had erratic meal timings and sleep patterns. A few months ago, while parking his car in the basement of his office building, he felt uneasy and began perspiring profusely. He managed to make it to his desk, but seeing his condition, his colleagues immediately called for an ambulance and he was rushed to the P.D. Hinduja Hospital. Ritwik had suffered a massive heart attack. Doctors summoned his family and informed them that his condition was serious and he needed a triple bypass surgery. After the surgery, Ritwik was put on insulin therapy and told that he urgently needed to alter his lifestyle.

Ritwik's attitude to diabetes was no different from that of millions of Indians. According to the Diabetes Atlas, out of 4.9 million diabetes deaths in 2014, one million occurred in India. There are already 66.84 million Indians with diabetes; an estimated 80 million more in the pre-diabetes stage. By 2030, it is estimated that there will be 101.2 million diabetics in India. What is worrying is that less than 50 per cent of them meet their glucose targets; hence they are prone to related complications of the eyes, kidneys, healing of wounds, and increased risk of heart disease and stroke.

Only fifteen days before his heart attack, Ritwik's glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level—which shows the average glucose level in the blood over three months—was 13 per cent. The normal level is 7 per cent. For years, Ritwik never ate breakfast, nor bothered to exercise. Today, after overhauling his lifestyle, his HbA1c is 6.8 and he does not need to take insulin. He jogs 7km each day, carefully monitors his diet and does not eat after 8pm. “Earlier, all I cared about was work and climbing the corporate ladder,” says Ritwik. “Now, I don't get so stressed as I have managed to achieve a work-life balance. I enjoy my kids and spend more time with family.”

Though he took a while to realise the seriousness of diabetes and its complications, Ritwik was lucky enough to survive the heart attack. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death for people with diabetes, accounting for almost 50 per cent of deaths in people with type 2 diabetes. Statistics show that diabetes affects Indians a decade earlier than their western counterparts; and coronary artery disease, up to two decades earlier than their western counterparts. Unfortunately, most Indians are unaware of these facts.

Multiple factors make the incidence of heart disease and diabetes so widespread among Indians. “In India, there is genetic predisposition to both coronary artery disease and diabetes. Also, Indians do not tolerate obesity as well as other ethnicities; even a little bit of fat around the abdomen puts an Indian at higher risk for heart disease than same-waist Caucasians,” says Dr Roshani Sanghani, endocrinologist, P.D. Hinduja Hospital, Mumbai. “Many people in India have a sedentary lifestyle and do not exercise at the required intensity to build optimal cardiac fitness or muscle mass. Also, there is a tendency for carbohydrate-rich diets with inadequate amounts of protein. Insulin resistance, coupled with central obesity, increases the risk for heart disease in Indians.”

Empowering with exercise: Dr Roshani Sanghani at a workshop for diabetes patients at P.D. Hinduja Hospital, Mumbai | Vishnu V. Nair

Empowering with exercise: Dr Roshani Sanghani at a workshop for diabetes patients at P.D. Hinduja Hospital, Mumbai | Vishnu V. Nair

When diabetes is not controlled, blood vessels become vulnerable to damage caused by high blood pressure and fatty deposits on the artery walls. Diabetics are also more likely to suffer from hypertension and obesity. More than preventive measures, however, patients—and sometimes even their doctors—are often more focused on blood glucose control. “Most treating physicians are at the level of primary care and mainly focus on glucose control,” says Dr Prabhakaran Dorairaj, director, Centre for Chronic Conditions and Injuries at the Public Health Foundation of India. “Indeed, we now know that it is very important to control blood pressure and cholesterol among patients with diabetes for better long-term outcomes, particularly for prevention of heart attacks.”

If more diabetes patients were aware of their heightened chances of developing cardiac complications, they would take better care to evade the risk factors. The life expectancy of patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease decreases up to 12 years. “Fifty per cent of our patients are 50 years and above and have diabetes,” says Dr Tilak Suvarna, head of cardiology, Asian Heart Institute, Mumbai. “A large number of diabetes patients do not receive evidence-based treatment, which puts them at high risk for cardiovascular disease.” This is primarily due to the lack of health literacy in India. In the west, a diabetes educator spends time counselling the patient about how to manage the disease. In India, this practice is mostly non-existent.

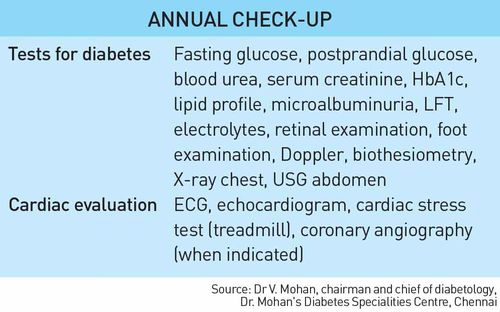

“To prevent micro-vascular complications, eye, kidney and nerve, blood glucose control alone, with HbA1c below 7 per cent, should be sufficient,” says Dr V. Mohan, chairman and chief of diabetology, Dr. Mohan’s Diabetes Specialities Centre, Chennai. “However, for prevention of heart disease, we need a multi-pronged approach and, apart from controlling the glucose levels, it is necessary to keep the blood pressure and lipid profile under control. In addition, regular physical activity, healthy diet, and decreasing stress would help prevent heart disease in people with diabetes.”

Dr Vijay Surase, consulting cardiologist at Jupiter Hospital, Thane, says that patients with diabetes don’t get classical symptoms of heart disease or heart attack and this leads to delayed diagnosis and treatment. “Diabetic patients don’t recover fast. They have elevated cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood, and have depositions of glycated protein in the blood vessels which narrows them, making it difficult to treat,” says Surase. If an average blood vessel is 3mm, it would be 2mm in a diabetes patient. It is even smaller in women because of their smaller frame. “In diabetes patients, the pumping rate of the heart is very low and there is a chance of developing cardiomyopathy which cannot be treated by angioplasty or bypass surgery,” says Surase.

Kuldeep Bachani had blockages in his arteries and was scheduled to undergo an angioplasty. However, when the surgeon found that his weight was 108kg, his blood sugar levels were above 400mg/dL, and that he had high blood pressure, he deemed Bachani unfit for the procedure. “My doctors told me to change my lifestyle,” says Bachani, 56. He read Dr Dean Ornish's Program for Reversing Heart Disease and changed his lifestyle by meticulously following the instructions in the book. Bachani turned vegetarian and completely cut out oil from his diet. He started walking daily for 45 minutes and eating small meals with raw fruits and vegetables. He also meditated for an hour every day, which gave him energy and reduced his stress. After a year of following this regimen, he lost 20kg and his cholesterol and blood sugar levels became normal. “I didn’t have a choice,” says Bachani. “It was do-or-die for me, but I realised it was possible to reverse heart disease with a good lifestyle. People now come to me for advice.” He has maintained this lifestyle for more than three years and now does not require any cardiac procedure. As his older brother died from heart disease, Bachani is keen on educating his nephews and children on preventive measures, ensuring they don't make the same mistakes.

Dr Anoop Misra gives an example of the effective power of lifestyle change to correct diabetes-related complications. “About 5 to 7 per cent of weight loss—with diet and exercise—in diabetes patients can decrease the blood sugar level by 50-70mg/dL, blood pressure level by 5 to 7 per cent, and triglycerides by 50mg/dL. This 'power' of improvement is nearly similar to (sometimes better than) the effects of the frontline drug metformin,” says Misra, chairman, Fortis-C-DOC Centre of Excellence for Diabetes, Metabolic Diseases and Endocrinology, and chairman, National Diabetes, Obesity and Cholesterol Foundation. "Such weight-loss alleviates pressure on the liver, kidneys, and heart, and help prevent complications. Moreover, a correct lifestyle is never glucocentric, but deals with all risk factors of heart disease and even cancers effectively.” Besides doctors, patients need the help of a team of nutritionists, physical trainers, nurses, and diabetes educators.

“Medications are important but they are add-ons,” says Sanghani. "The primary line of treatment is lifestyle change. Yet, as doctors and health care providers, we can do much better to truly guide our patients to embrace a lifestyle change. We need more providers really owning and championing it (as a cause).” Sanghani makes her patients attend a workshop on mindful eating to help them develop healthy eating habits. She also takes sessions on Diabetes Self-Management Education, developed on the “patient empowerment” model rather than the “patient compliance” model, which focuses on getting patients to take better care of themselves rather than doing things simply because the health provider expects them to.

Dorairaj recommends that the government, too, joins in the fight against diabetes through non-personal policy measures such as taxation on sweetened beverages, and tax benefits for improving supply of fruits and vegetables or reducing their post-harvest storage and transportation losses. “To do away with physical inactivity, an enabling environment is needed,” says Dorairaj. “These include freeing up footpaths for walking, cleaning and improving existing parks, and incorporating health-friendly policies in smart city plans.”

To help diabetics eat healthily, a group of diabetologists of the United Diabetes Forum have started the Blue Dot initiative. A blue dot on food packets will indicate the food is diabetic-friendly, similar to the green dot indicating vegetarian food and a brown one indicating non-vegetarian. Says Dr Rajiv Kovil, secretary of the forum, “As diabetes patients are often at a loss about what to eat when they go out, we plan to have blue dots on packaged food and restaurant menus to make healthier food accessible to them.”