Kanti Rai, 67, is watching the screen in front of her with rapt attention. As she moves her legs—connected to a machine—an inch higher, a tiny character on the screen moves faster or jumps higher. This earns her more coins. Every time her coin count goes up, Kanti's husband, Awadhesh, and her physiotherapist cheer for her and encourage her to try harder. The duo’s glee over Kanti's ability to complete this seemingly small task is because she was bedridden for three months after suffering a stroke on March 19.

Kanti's right side was paralysed following the stroke, and she lost her ability to speak and move. “She was first admitted to a nursing home after she suffered from high blood pressure, giddiness and vomiting. Then, she had a stroke and we decided to shift her to Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital, [Mumbai], where she underwent extensive treatment for the next three months. An MRI revealed a part of her brain was swollen. Fortunately, there was no bleeding,” says Awadhesh.

Kanti was in the ICU for a month and a half before she was shifted to a ward. Her condition was monitored round the clock for another month. “After that, she was shifted to a private ward. The next big challenge was to enable her to move her right leg and arm and to make her talk again,” says Awadhesh.

When a stroke occurs, the blood supply to an area of the brain is reduced or completely cut off. Owing to this, the brain cells are left deprived of oxygen and die. In case of a major stroke, patients suffer from muscle control loss and lose their ability to speak. According to a 2016 study published in the Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, stroke is the most common cause of chronic adult disability.

While Kanti was undergoing physical, speech and occupational therapy, she was advised to undergo robotic rehabilitation therapy along with virtual reality therapy (VRT) to regain mobility. When she was finally discharged from the hospital on June 26, she had regained 80 per cent movement in her right leg and 90 per cent in her right arm. However, the progress was gradual and was accomplished after 42 sessions of robot-assisted therapy along with virtual reality therapy, which cost the Mumbai-based couple around Rs 2 lakh.

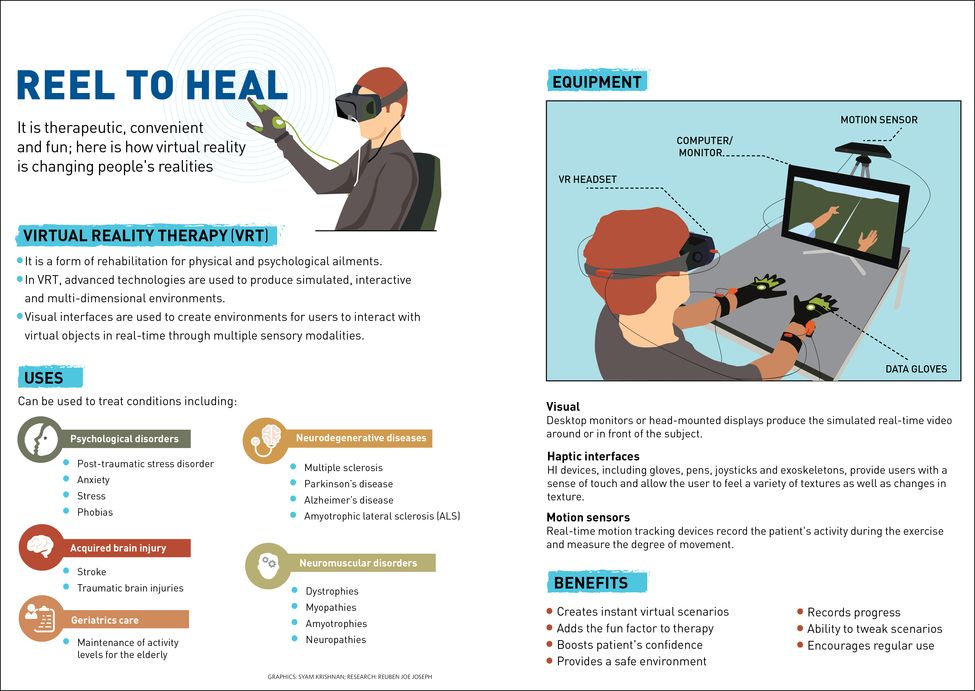

Dr Abhishek Srivastava, a neurorehabilitation specialist and director of the Center for Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital, says for patients like Kanti, robot-assisted therapy is a game changer. “For stroke patients, virtual reality therapy is either used individually to stimulate centres in the brain, which were not being used before, to enable movement or as part of neurorehabilitation [a procedure that aids recovery from a nervous system injury]. VRT can be used when there is some form of mobility in the patient,” he says. In Kanti's case, since she was

completely bedridden, “robotic-assisted therapy helped in moving her hand and leg virtually at first,” he adds. There are two types of robotic devices—end-effector [connected to the end of a robot arm] and exoskeleton, but at the hospital, exoskeleton devices are more commonly used.

Dr Abhishek Srivastava | Sameer Joshi

Dr Abhishek Srivastava | Sameer Joshi

For a stroke patient, high-intensity training can go a long way in recovery, and doctors rely on neuroplasticity for functional outcome after a stroke attack. Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to organise itself functionally and physically by forming and reorganising synaptic connections after an injury. Doctors say patients see some form of improvement usually after completing at least 15 sessions of robot-assisted therapy and VRT.

Kanti was able to regain her lost movements and reflexes over a period of one and a half months by using this man-machine interaction for two hours every alternate day during her stay in the hospital. “Now, she can walk with the help of a walker or stick, which was previously not possible. She still lacks the confidence to walk without support, but I am optimistic about her condition improving,” says Awadhesh.

So, how does robotic-assisted therapy and VRT work? In order to improve the patient’s balance, motor movements, reflexes and mobility over a period of time, the man-machine interaction mainly comprises a locomotion therapy equipment known as the Lokomat, which is used to provide support for the lower body, along with the Armeo or upper limb rehabilitation device. In the beginning of the therapy, when patients have no power or control over their limbs, the therapy is fully remote-assisted.

Doctors and physiotherapists use these equipment to create a real-life environment and to monitor the patients' responses and progress. “In some cases, we use biofeedback, where a graph appears on the screen and shows the patient his or her range of movements in the immobile limb. In other cases, we use video games after the Armeo or Lokomat is strapped to the patient’s affected limb. On the screen, they will have to lift an object or move their arm or leg to gain more points,” says Srivastava. Or else, the virtual feedback will show the patient walking on a mountain, surrounded by cattle, and the patient will have to navigate his/her way through it. With these simulations, the patient is able to gradually move the limb on their own. This is done under the constant supervision of physiotherapists and doctors.

A study published in the Journal of Stroke in 2013 says robot-assisted therapy with exoskeleton devices might not be able to fully replace conventional physiotherapy for improving gait function in stroke patients, but is recommended for use in combination with conventional physiotherapy. After being discharged from the hospital, Kanti was advised to discontinue robot-assisted therapy and VRT following her progress. She is now undergoing conventional physiotherapy.

For Henry Joseph, 25, it seemed like his life had come to a screeching halt after he suffered a stroke in September 2016. He then had to undergo a minor surgery to remove a blood clot in his brain and was hospitalised in Apollo Hospitals, Chennai, for a month. He had a partial paralysis on the left side, and underwent conventional physiotherapy for six months, followed by VRT and robot-assisted therapy.

Dr Raj Prasanna Chief | R.G. Sasthaa

Dr Raj Prasanna Chief | R.G. Sasthaa

“For the last three months, I have been undergoing VRT for 30 minutes every day and the best part about this form of physiotherapy is that it is so much like playing a video game. This helps me in staying motivated and focused as I have to score more points, which simultaneously improves my balance and coordination,” says Henry, who used to work as a software engineer.

After the first one month of VRT, Henry was able to regain movement in his left hand and there has been an improvement in coordination between his legs and hands as well. “My favourite game is the one where I have to catch an animal peeping out of different holes,” he says. However, he is yet to regain movement in his left leg. He is hoping to make a full recovery soon so that he can resume work in the next few months.

Stroke patients are not the only ones who benefit from robotic-assisted therapy and VRT. This technology is also used by neurologists and physiotherapists to treat accident victims and also patients with neurological conditions like Parkinson’s disease, cerebral palsy, children with developmental delays, autism, multiple sclerosis and peripheral nerve damage.

“VRT helps in training the neural activity to send signals to the affected limbs and eventually enable them to move,” says Dr Raj Prasanna, chief, physiotherapy and rehabilitation at Apollo Hospitals, Chennai. “The virtual environment psychologically motivates the patient as they are provided with constant positive reinforcements like a smiley face or sounds each time they achieve a new level. If required, joysticks and Wii consoles are also used, as VRT is tailor-made for each patient and their course of rehabilitation depends on the creativity of the physiotherapist.”

While studying MBA in Goa, Aniket Mishra injured his back and fractured his spine in a bike accident. After undergoing surgery at Manipal Hospitals, his doctors advised him to go to the Indian Spinal Injuries Centre (ISIC) in New Delhi for rehabilitation. “I had to undergo another surgery and was left wheelchair-bound owing to paraplegia. While going through conventional physiotherapy, I was advised to also try VRT to improve my balance and to be able to stand again,” he says. Since last October, he has attended six sessions, lasting one to two hours, of VRT a week.

Now, Aniket is able to walk with the help of support and has regained movement in his right leg. He has also been doing strength training with weights and swims regularly. “VRT, with the help of skiing and hula hoop video games, helped in improving my balance by training me to put equal weight on my left and right side,” he says.

Another patient at the ISIC, 65-year-old Sushma (name changed) has been struggling to cope with the symptoms of spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA), a group of genetic disorders characterised by incoordination of gait that progresses slowly over the years. SCA is also known to cause poor coordination of hands, speech and eye movements. “When I was diagnosed with this genetic disorder a decade ago, I was told there was no cure and that my only option was to control the symptoms with medication and exercises,” says Sushma, a Delhi resident. “However, I was unable to do the exercises regularly at home and that is when a neurosurgeon recommended VRT. The best part about VRT was seeing wheelchair-bound patients and others like me opting for video games, which kept us motivated to do these exercises. In the last few months, my balance has improved.”

Dr Chitra Kataria, chief of Rehabilitation Services and principal of ISIC Institute of Rehabilitation Sciences, says the main goal for such patients is to improve balance, strength, capacity, endurance and even aerobic capacity. “We first assess a patient according to their cognitive impairment, muscle strength, balance and range of movement and then customise their programme accordingly. For VRT and rehabilitation, it is important to remember each patient is different,” says Kataria.

Prasanna says for patients with neurological diseases and other movement related issues, VRT is possible only if they have sufficient cognitive abilities. “The patient should be able to understand and carry out the orders given to him by the therapist during VRT. If their cognitive abilities have been affected due to cerebral palsy or any other neurological condition, the patient won’t benefit from VRT at all,” he says.

For children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, doctors use colour therapy and sounds to help them. When it comes to VRT, geriatric patients tend to benefit from group therapy. Prasanna says patients with urinary incontinence can also benefit from VRT. “The electromyography shows their muscle activity and we generate a pressure base for tightening pelvic floor muscles. Once the patient attains their target, they are rewarded with a bonus on the screen and sounds to keep them motivated,” says Prasanna. He says most patients are women over the age of 50 who have poor control over their urine and bowel movements due to menopause, changes with age, childbirth or neurological disorders. In men, incontinence could be due to prostate enlargement or cancer. “To treat urinary incontinence,” says Prasanna, “pads are placed on the patient's perineal area and they are used to record the electrical activity of the muscles, which is also known as electromyography. This way, we know if the patient is using the right muscles or not.”