Melissa Baker, 41, had been feeling itchy for a few months and then one evening she felt a lump in her neck. She went to see her doctor and by the end of the week, she was diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma. She was told it was a “good cancer” and that she would be cured with six months of treatment.

Unfortunately, that wasn't the case. When the first line treatment failed, she underwent a stem cell transplant and nearly died from pneumonia in the lead-up to it. The transplant also failed. This was followed by treatment with an expensive targeted chemotherapy drug. After an initial good response, Melissa's lymphoma started progressing again.

“I was running out of options at this point and my outlook was pretty grim. I found a new haematologist and enrolled in a clinical trial for Keytruda [pembrolizumab], an immunotherapy drug that allows my own immune system to fight the cancer,” says Melissa, a pathologist by profession.

After just three treatments and virtually no side effects, she was in remission and she remains in remission one year on, still having treatment. “This drug has literally saved and transformed my life. I have returned to work after being unable to work for two-and-a-half years. I am enjoying a near-normal life,” says Melissa, mother of a four- and a nine-year-old.

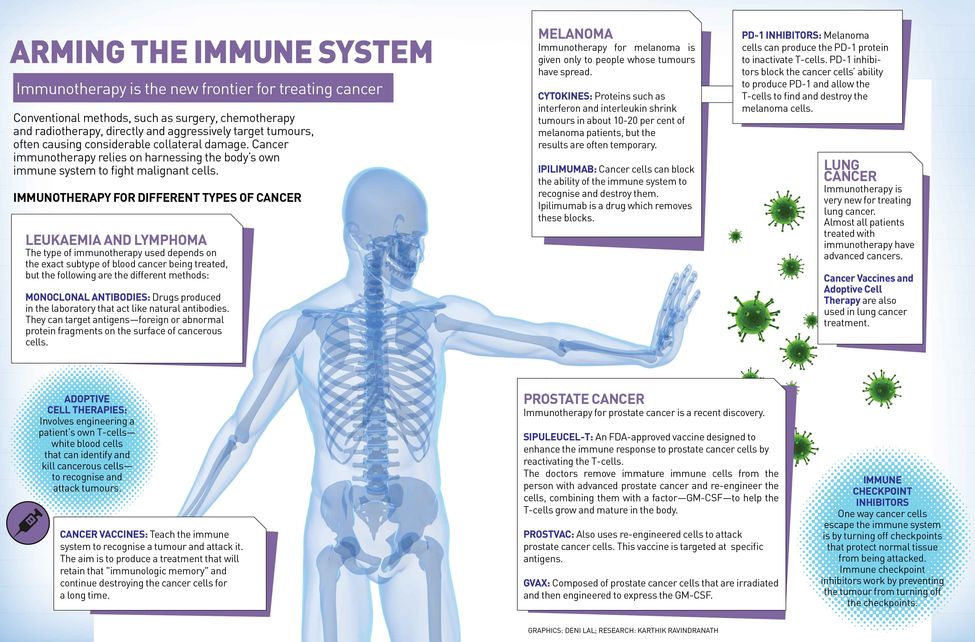

In recent years, researchers have made significant strides into finding a cure for cancer, which claim 8.2 million lives annually. Cancer immunotherapy, which relies on harnessing the body’s own immune system to fight malignant cells, is the new frontier for treating cancer alongside the conventional therapies—surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Globally, more than 100 clinical immunotherapy trials for a whole range of cancers are underway. “Traditional methods of cancer treatment—surgery, radiation and chemotherapy [slash, burn and poison, as they are not-so-fondly known]—directly and aggressively target tumours, often causing considerable collateral damage. Immunotherapy leaves it to T-cells [a type of white blood cells that can identify and kill infected, damaged or cancerous cells], the assault troops of the immune system, to do the searching and destroying,” says Professor Grant McArthur, associate director of Cancer Research and head of the Cancer Therapeutics Programme at Melbourne’s Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre.

Melissa Baker | Neena Bhandari

Melissa Baker | Neena Bhandari

It was in the 1890s that a New York surgeon, Dr William B. Coley, first came upon the idea of cancer immunotherapy while removing tumours from his patients. He noticed those patients whose tumours became infected often had a better remission. He infected patients with strep bacteria in the hope that they would have a strong response that might eradicate their tumours. He called it Coley’s toxins, but didn’t fully understand why it worked sometimes and often did not.

Today, immunotherapy has reached the forefront of oncological medicine in cancer treatment largely because of major breakthroughs in two areas. “One is 'checkpoint blockade', and there has been quite an amazing success story there in inhibiting inhibitory receptors on the cells of the immune system, particularly the T-cell receptor that] is really the key endpoint for all cancer immunotherapy. That has been very successful with drugs like Opdivo [nivolumab], Yervoy [ipilimumab], Keytruda, which have been effective in patients who have a variety of tumours in melanoma, lung, renal cell, bladder, head and neck cancers and Hodgkin’s lymphoma,” says Dr Laurie Glimcher, who is on the Cancer Moonshot 2020 Committee, advising US President Barack Obama.

Scientists now know that T-cells have built-in brakes, known as 'checkpoints', to prevent them from attacking a person’s own healthy tissue. It was Dr James Allison of the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, who first identified one of these checkpoints—a protein called CTLA-4 found on the surface of T-cells—which led to the development of the first-ever drug Yervoy that blocks CTLA-4 antibody.

But 'checkpoint blockade' only works in a minority of patients and doesn’t extend to all tumours. So, additional agents are required to activate the immune system. “Those mechanisms and those protocols include adoptive T-cell therapies as well as the development of vaccines and studying a very immunosuppressant tumour microenvironment [microenvironment is the tissue immediately in and around a tumour], where our own work comes in,” says Glimcher, dean of Medicine at Cornell University, and president and CEO of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in the US. “If you take out a chunk of tumour, you will see that the majority of that tumour is not made up of tumour cells but it is made up of a variety of immune cells that are highly immunosuppressant.” Certain tumours, she says, are particularly affected by this very immunosuppressant tumour microenvironment. Ovarian cancer is one of them. “In preclinical studies, we have demonstrated that turning off the gene XBP1 [X-Box Binding Protein 1] restores the immune responses against ovarian tumours. The high death rate in ovarian cancer has remained the same over the last 40 years because there have been no new therapeutic strategies. This study offers us a new approach,” says Glimcher.

Her team's research basically showed that a pathway called the ER (endoplasmic reticulum) stress response had some surprising functions in cancer. “First of all, it attacked the tumour cell directly,” says Glimcher. And, for this, her team studied triple negative breast cancer, one of the most aggressive breast cancers that affects young women. “Aside from chemotherapy, it really has no targeted therapeutics. We showed that simultaneous pathway in triple negative breast cancer cells led to progression of tumour in patients’ xenograft models. We then went on to look at silencing this pathway, which is driven by a transmembrane ER sensor called IRE1alpha whose downstream substrate is a factor called XBP1, which was isolated in my laboratory two decades ago. Right now we are in the midst of studying a number of different cancers to see how broadly this ER stress pathway can convert an immunosuppressant tumour microenvironment into a tumour microenvironment that actually activates the endpoint cell, which is the T-cell,” says Glimcher.

Professor Grant McArthur

Professor Grant McArthur

Adoptive cell therapy, on the other hand, uses the concept of vaccine to alert the immune system to the existence of tumours. Professor Jay Berzofsky, chief of the vaccine branch, Center for Cancer Research at the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda (US), has developed a vaccine that targets prostate cancer. “These are therapeutic vaccines that are given after the person already has the disease, in this case cancer, to try to awaken the immune system and to direct it towards the molecules in the cancer,” says Berzofsky. “If one can do that, then one can take advantage of these other mechanisms such as 'checkpoint blockade' to try to enhance that response. So it is expected that cancer vaccines that induce immune response and 'checkpoint blockade', which allows that response to be fully effective, should work together and be more effective.” He says they have had some early success, where almost three-fourth of early stage prostate cancer patients have had some beneficial effect and slowing of tumour growth. They have now started a randomised placebo-controlled phase 2 trial to test it further.

Immunotherapy drugs work differently in individuals depending on their immune health and genetic makeup. It may restore perfect health in a few, reduce tumour size in some and do little or nothing in others.

David Mitchell, 54, had a melanoma surgically removed 23 years ago. Suddenly 16 months ago, the father of three had a brain haemorrhage and was rushed to emergency. The haemorrhage and a brain tumour were surgically removed. However, two more brain tumours were found and further scans revealed that the cancer had metastasised and spread to the intestines and kidney. He underwent targeted chemotherapy, but reacted badly to it.

“The oncologist then asked me if I would like to participate in the trial for the immunotherapy drug, Keytruda. It hadn’t been trialled for brain tumour so the doctors weren’t confident that it would necessarily enhance my life expectancy. I have been on the drug for the past 12 months. While chemotherapy had knocked me out, I have had no side effects from Keytruda. The last scans show only one tumour and I could be in complete remission. When my oncologist gave me the good news, there was a sense of relief and disbelief at the same time. From a prognosis of 12 months, I have got my life back,” says David, reassuringly holding his wife’s hand.

So, what is the success rate of immunotherapy versus other treatments? Or, are multi-modality treatments the way to go? McArthur says, “The unique thing about immune-based therapies is the duration of response that appears far better than most [but not all] conventional chemotherapies or targeted therapies. Overall, the response rates are not that much higher, it is the length of response that we are excited about. Combinations with other therapies is a very promising prospect as lab-based studies indicate combinations—include radiation therapy, chemotherapy and targeted therapy—may lead to even further improvements. But it is early days for these combinations in clinical trials.”

Dr Laurie Glimcher | Neena Bhandari

Dr Laurie Glimcher | Neena Bhandari

The new cancer immunotherapy is revolutionising the treatment of cancer, and the lessons learnt from cancer can also be applied to HIV. In 2015, there were 36.7 million people living with HIV globally. Professor Carl H. June, director of translational research in University of Pennsylvania’s Abramson Cancer Center, who is considered the 'father of cancer immunotherapy', says, “We are only a year away from the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] approval for gene transfer using CAR T-cells for cancer [chimeric antigen receptor T-cells is a technology that modifies patients’ own cells to attack their cancers]. There is emerging data that those similar approaches in cancer will also have promise in HIV. We have learnt that the part of the immune problem with cancer is the same as HIV. So the cancer therapies will provide the field with the infrastructure to move towards more cure research for HIV.”

Also, laboratories are working with pharmaceutical companies to take drugs that have gone through phase 1 clinical trials for one purpose and were not effective in that setting but were shown to be safe to see if they may perhaps work in cancer. For example, Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG), which is a vaccine used to prevent tuberculosis, is an effective intravesical [drugs are put directly into the bladder through a catheter] immunotherapy for treating early-stage bladder cancer.

Many new drugs in development are now being awarded accelerated or breakthrough status by the US FDA, which gets them through phase 1, phase 2 and phase 3 trials much more quickly with smaller cohorts of patients.

Professor Jay Berzofsky | Neena Bhandari

Professor Jay Berzofsky | Neena Bhandari

Cancer immunotherapy treatments, however, are currently prohibitively expensive and beyond the reach of most patients. For example, the price of Keytruda currently sits at about $8,800 [around 05.8 lakh] per dose. MacArthur suggests an access model similar to HIV therapies' to make these breakthrough medicines available to more patients worldwide. Participating in clinical trials is one way of accessing these treatments, but a majority of patients don’t participate in trials. “We need to change that paradigm because to my mind each patient’s best clinical care requires offering them experimental therapies if the current state-of-the-art therapies for their unique tumour are not adequate,” says Glimcher.

David Mitchell with his wife. He had two brain tumours | Neena Bhandari

David Mitchell with his wife. He had two brain tumours | Neena Bhandari

According to Glimcher, combination therapy is going to be the ultimate requirement so that no patient with cancer has to die of their disease. “Just as HIV and AIDS was converted from a uniformly lethal disease into a chronic disease,” she says, “we need to provide therapies such as vaccines, adopted T-cell transfer, checkpoint blockade and new agents like, we hope IRE1 inhibitors, that will reverse an immunosuppressant tumour microenvironment.”