Lights off, and the demons would creep out from memories past. The room went dark, as did her mind. Insia Dariwala, 43, was ten when she was sexually abused—“16 times by people I knew, including family members". “The number was something I only got to know under hypnotherapy. I felt betrayed and though on a superficial level, the emotional and mental wounds had healed, below that layer, something had altered psychologically,” says Dariwala. "It has been only two years since I can sleep alone in the dark. Previously, that would have been impossible as I was sexually abused in a dark room.”

Over the years, Dariwala experienced a lot of unresolved anger along with migraines, bouts of depression and anxiety. It was only in 2009 that the Mumbai-based filmmaker could come to terms with the assault. “While doing some research for my movie on child sexual abuse [The Candy Man], I read a few studies online on post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD] and how sexual abuse survivors could suffer from it. It was only then I realised how anxiety disorders like phobias and other symptoms like migraines, flashbacks, nightmares, insomnia and constipation are common among child sexual abuse survivors,” she says. She laments over the lack of support group programmes in India and says she was finally able to deal with her psychological trauma after reaching out to other child victims through her NGO, The Hands of Hope Foundation.

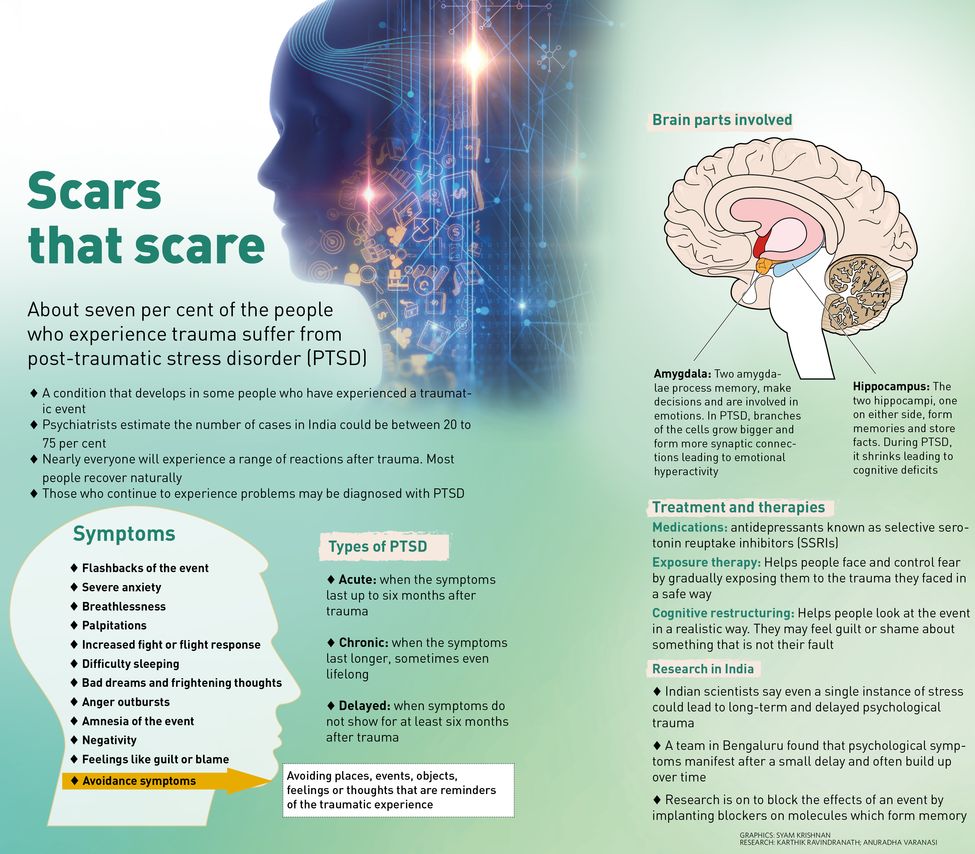

For nearly three decades, Dariwala was left with unseen scars that manifested in her mind. The most predominant impact of all anxiety disorders, including PTSD, is emotional, says a team of researchers from the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) and Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine (InStem) in Bengaluru. Even a single instance of stress could lead to long-term and delayed psychological disorder.

Charlotte Wang, who, along with her husband, suffered from PTSD following an accident | Amey Mansabdar

Charlotte Wang, who, along with her husband, suffered from PTSD following an accident | Amey Mansabdar

Since 2005, the team, led by Sumantra Chattarji, professor of neurobiology at the NCBS, has been studying how a stressful or traumatic incident can affect the brain. Chattarji started his laboratory in NCBS in 1999. Having never worked on stress before, he says, what struck him most as an outsider was that all previous research on stress disorders focused largely on cognitive symptoms. It was observed that patients with PTSD have cognitive deficits. So, the studies were centred around one area of the brain—the hippocampus, which is crucial for forming memories and storing facts—and how stress damaged it structurally and functionally.

But what baffled the researchers was that the damage to the hippocampus did not explain how and why patients experienced strong emotions following a stressful incident. “We realised that in order to understand the emotional symptoms of stress, we need to look at the neighbouring region of the brain, called the amygdala, which is involved in emotions,” says Chattarji. “In previous studies, nobody had really looked at what stress does to the amygdala and the brain cells in it and there was a glaring gap in knowledge.”

According to previous studies, the hippocampus volume in PTSD patients shrinks, which is visible even in an MRI scan. Also, the neurons in the hippocampus shrink as their branches are lost and all the molecules involved in maintaining normal structure are suppressed. However, the Bengaluru researchers observed that all these downhill effects could not explain the increase in emotions. “The question was what happens in the amygdala differently that explains the increase in emotions as opposed to the decrease in cognition,” says Chattarji. “When we did the same cellular analysis in the beginning, surprisingly, we found the amygdala cell’s branches growing bigger and forming more synaptic connections.”

The researchers then started getting insights into how stress can cause hyperactivity in the amygdala. “For the next few years we worked hard to show how at any time any form of stress caused the amygdala cells to grow bigger and form more synapses,” explains Chattarji. If you have these changes at the cerebral level—whatever be the reason, stress or genetic—you will get higher anxiety, he says.

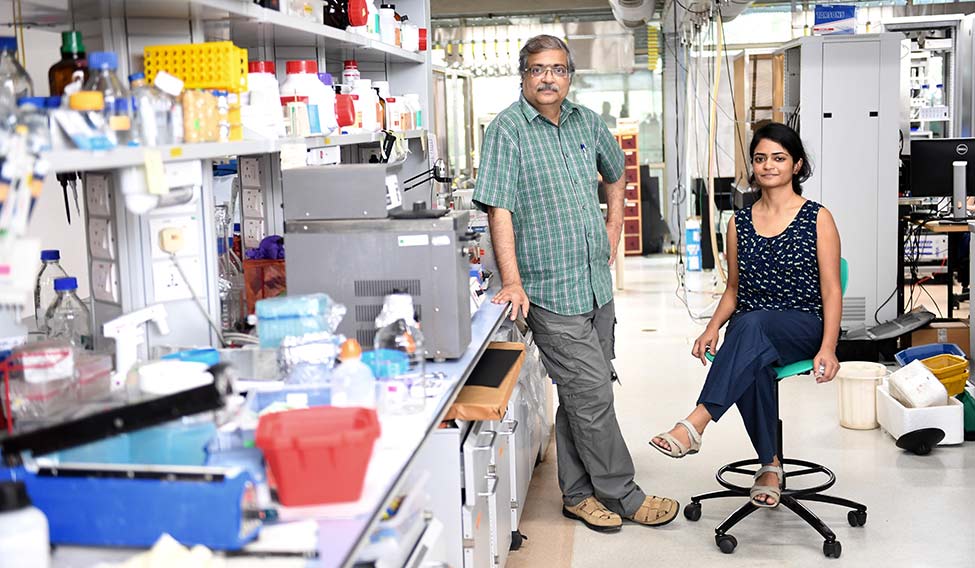

Sumantra Chattarji(left) and Farhana Yasmin | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

Sumantra Chattarji(left) and Farhana Yasmin | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

The team was able to make this discovery after stressing lab rats for two to six hours daily, which is known as repeated or chronic stress. While long-term stress gave immediate results, the team then decided to subject the rats to one episode of stress that lasted two hours and see its effect on the rats and amygdalae over the next ten days. A day later, there was no increase in anxiety among the rats or changes in the amygdalae. But, after ten days, new synaptic contacts were fully formed and the animals were found to be experiencing anxiety.

That is when the scientists knew they had made their first breakthrough. “When you have a traumatic or life-threatening experience, the physical symptoms may be immediate, but the psychological symptoms often manifest much later on and build up over time,” says Chattarji. This gap between the actual trauma and the eventual manifestation of the strong emotions, he says, is the hallmark of PTSD.

But, at times, the psychological impact is visible soon after the trauma, like in the case of Charlotte Wang and her husband. Last August, the Mumbai-based couple met with an accident while travelling from Ganpatipule to Mumbai in a friend's car. They underwent an extensive treatment for multiple fractures. But post recovery, they suffered from mood swings. “We were constantly angry and had fights more often and we suffered from bouts of depression,” says Wang, 27. “Despite resuming with work while my fractures were still healing, I had faced difficulties in concentration on daily tasks for around three months following the mishap. No one had told us about the mental trauma we would suffer from or how to deal with the constant anxiety. From being a happy and extroverted couple, we became isolated and angry individuals due to PTSD.” The duo is now paranoid of traveling by road as they are scared of the trauma of another accident. After surviving the physical and emotional wounds of the road accident, the couple strongly advice other accident victims to consult a psychiatrist to deal with the stress as a part of their treatment, just like they would consult a physiotherapist.

Dr Amit Desai, consultant psychiatrist, Jaslok Hospital, Mumbai, says there are two types of PTSD—acute PTSD that lasts for around six months and chronic PTSD that lasts for years on end and sometimes even lifelong. “However, chronic PTSD is not very common,” he says. “The symptoms of PTSD are usually severe anxiety, breathlessness, palpitations, flashbacks or repetitive memories and nearly 7 per cent of the patients who have experienced traumatic or near-death experiences suffer from this mental disorder.” The standard treatment for PTSD, he says, includes taking antidepressants—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—along with counselling and psychotherapy. Dr Sagar Mundada, a Mumbai-based psychiatrist, says apart from SSRIs, PTSD patients need to undergo behavioural therapy in order to manage their stress and prevent hyperactivity.

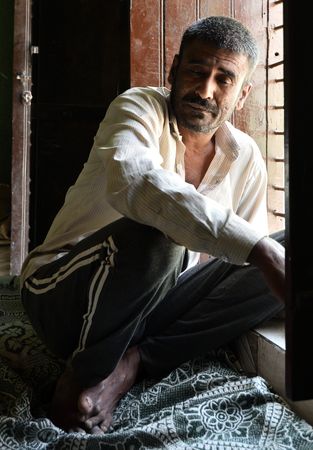

Naik Suraj Bhan, 45, was discharged from the Army on medical grounds after he developed severe psychiatric symptoms. He had served in counterinsurgency operations for eight years | Sanjay Ahlawat

Naik Suraj Bhan, 45, was discharged from the Army on medical grounds after he developed severe psychiatric symptoms. He had served in counterinsurgency operations for eight years | Sanjay Ahlawat

In order to figure out how PTSD can be prevented altogether, the Bengaluru researchers conducted another study. They took a cue from a study conducted in the United States where a small per cent of ICU patients who suffered from PTSD were given cortisol, a stress hormone, following treatment. The study found that cortisol helped in reducing the prevalence of PTSD symptoms later in life for those patients. “This was very strange and made no sense to us since cortisol is the hormone that triggers stress in the first place,” says Chattarji. The Indian team tried the same on their lab rats, and found that cortisol helped in preventing the delayed effects of PTSD like anxiety or the formation of synapses in the amygdalae ten days later. However, prescribing cortisol to PTSD patients regularly might not be advisable as it could have severe side effects, says Chattarji. Another major drawback is that every animal model has its own limitations. The researchers were only able to measure the rats’ anxiety levels and could not determine if they were suffering from flashbacks.

“If faced with an emergency situation, for example, a road accident, cortisol can help in fighting against PTSD symptoms,” says Mundada. “However, it acts on only certain disturbances caused by PTSD and is in no way a standard treatment and is still in the experimental stages, as it still needs to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration.”

For further understanding what goes on in the amygdala during stress, the lead author of the study, Farhana Yasmin, studied how the formation of new synapses in the brain is one of the signatures of memory formation. “Given the delayed formation of synapses in the amygdala after a stressful incident, we know the molecules for memory formation and we focused on one such molecule known as the NMDA [N-methyl-D-aspartate] receptor,” explains Yasmin, 29.

A synapse releases chemical transmitters that activate the next neuron. This chemical transmitter is known as glutamate, which is like a key that can unlock the gates to the next neuron. While glutamate triggers synaptic currents in the next neuron, it can connect to several different types of receptors and one of the subtypes is the NMDA receptor, which is also known as the golden molecule for forming memories in the hippocampus and amygdala.

“We surgically implanted a pharmacological blocker in the animals against the NMDA receptor, owing to which the chemicals blocked the glutamate and did not allow the current to flow through. The drug was infused in a targeted fashion only to the amygdala in such a way that as soon as the stress starts, we release the drug,” says Yasmin. Following that, the NMDA receptors, even after the rats were subjected to physical stress, were no longer activated in the amygdalae. There was, therefore, no hyperactivity in the amygdalae ten days later and the animals did not suffer from increased anxiety. “This confirmed that NMDA receptors are crucial for stress-induced delayed effects in the amygdala, and if you can find a way to block the NMDA receptors, you can possibly block the effects of a stressful incident,” she says.

However, the limitation of this finding is that in humans, it is not possible for doctors to infuse a blocker before or during a stressful life incident. “In real life, for therapeutic intervention, the only thing we can learn from this are about the molecules involved, and doctors will have to adopt a very different strategy,” says Chattarji. “However, that strategy is fraught with danger. Also, NMDA receptors are required for other memory formations as well. So you can’t just have a pill of NMDA blocker every morning in anticipation of something bad happening.”

But, these findings, say researchers, have given them a start on how to prevent PTSD. In another study conducted by Yasmin, which is based on longstanding data that states cannabis helps patients of PTSD, depression and anxiety, she developed a substitute drug that yielded similar results. “Cannabis has its own set of side effects like psychosis and drowsiness,” she says. “So, I used a similar drug that targets a part of the brain called the endocannabinoid system. This was mixed in the animals’ food and ten days later we found it could block the physiological and structural effects of stress on the brain. This is a more realistic intervention and something we could try post stress. All of these studies are getting us closer to multiple targets to alleviate stress.”

Despite these new findings, the most puzzling aspect for researchers is that not every trauma victim suffers from PTSD. Psychiatrists and researchers say the reason could be genetic or due to past experiences in the patient’s life. For instance, Sunoj Matthew, 47, from Mumbai was almost run over by a lorry while riding his bike on a busy street in Mulund last October. He suffered multiple fractures in his right arm and had to undergo two surgeries and extensive physiotherapy that cost more than Rs 10 lakh. Despite that, he says once he was able to use his right arm again, he resumed riding his bike as usual. “My mentalhealth did not get affected nor did I suffer from increased anxiety or flashbacks of the incident,” he says. “My life is almost back to normal and if a stranger met me, s/he wouldn’t be able to tell that I was close to losing my life a few months ago.” He resumed work in February and is undergoing physiotherapy to prevent water retention in his right arm.

Chattarji says insufficient cortisol in certain individuals makes them more vulnerable to stress disorders. “It is contradictory but we showed that is the case,” he says.

According to studies in the US, only ten per cent of the general population suffers from PTSD. There is no data on the prevalence rate of PTSD or other anxiety disorders in India, but psychiatrists estimate it could be anywhere between 20 per cent to as high as 75 per cent among the general population, says Dr Niti Sapru, president of the Bombay Psychiatric Society.

Her youngest PTSD patient, says Sapru, was only two years old. The patient lived with her parents abroad and she was at the risk of being taken away from them by the authorities due to allegations that her parents were unable to take care of her. “The child would watch her mother crying and expressing anger and other such strong emotions on a daily basis, which resulted in the baby suffering from PTSD,” says Sapru. When the child moved to India for six months, she was able to recover from the symptoms gradually after counselling.

Among US war veterans, around 30 per cent are diagnosed with PTSD, says Yasmin. In India, too, there is no denyingthe fact that those who have served in the armed forces are prone to PTSD.

Naik Suraj Bhan, 45, was discharged from the Army on medical grounds after he developed severe psychiatric symptoms. He had served in counterinsurgency operations for eight years. In 2002, while he was deployed in a peace area, he had a fall while on duty, following which he was diagnosed with ‘unspecified psychosis’ along with 40 per cent disability, says Navdeep Singh, an advocate in Punjab and Haryana High Court. To make matters worse for the family, they had to fight for his pension in the High Court and then the Supreme Court. His pension was finally released in 2013. The pension is his family's main source of income.

Today, Bhan is confined to his bedroom in Bhiwani, Haryana, and is being taken care of by his wife, who does odd jobs, and four children. “He has been suffering from regular outbursts and increased anxiety since 2002. He was put on psychiatric treatment by the Army, which we continued for a few years. But he stopped taking his medicines a few years ago as the treatment did not help in reducing his symptoms,” says daughter Rinki Bhan, 20.

According to advocate Singh, also the founding president of the Armed Forces Tribunal Bar Association, after serving in counterinsurgency operations for eight years, Bhan suffered from severe PTSD, which aggravated to an unspecified psychosis after the fall in 2002.

“There used to be a time when he would walk around the village naked,” says Jagbir Singh, Bhan’s neighbour. “He would go to a nearby jungle in the middle of the night. He had to be chained for his own safety. However, it has been a few years since we have stopped restraining him physically. Now, he stays at home all the time.”

Navdeep Singh says it is unfortunate that psychiatric disorders are not being taken seriously by the Army despite its high prevalence and how badly it is affecting soldiers’ lives. “In one case, a soldier who was posted in Kashmir started suffering from PTSD symptoms like nightmares, flashbacks and increased anxiety. This happened after his patrolling party was attacked by militants,” he says. “He would wake up screaming in the middle of the night and when he underwent a psychiatric evaluation, his condition was dismissed by the doctor as ‘disturbed sleeping patterns’. This was absolutely shocking. The system is against the soldiers and is subjecting pointless litigation on disabled soldiers to deny them their pensions which they are entitled to.”

Like most mental disorders, PTSD, too, is either ignored or overlooked. There is a need for more awareness and research in India, and studies, like the one done by the Bengaluru researchers, will go a long way in understanding and dealing with mental illness.