In the film Sully, Captain Chesley Sullenberger makes a sudden decision that, he thinks, will help save the lives of his passengers and crew, even as both engines of his craft are unexpectedly destroyed in mid-air. Though he pulls it off, the question remains whether his action may have actually endangered the lives of his passengers unnecessarily. The human element, which he so relied on, may well have erred.

AUTOMATION

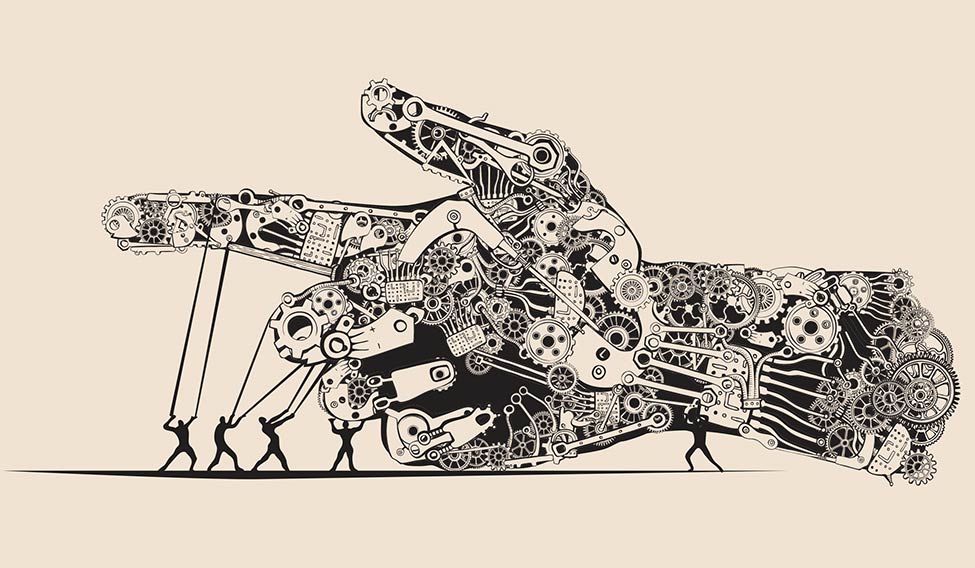

Our world is pushing itself towards becoming increasingly automated and digitised. Stuff that was mechanical is passé. In the 'smart' zone we aspire for, office ware and all systems at home will be digitally controlled, from refrigerators to centralised electrical systems.

Automated or driverless cars are the next big push. At least four giant US companies are working on the technology, and now they have federal backing. With about 40,000 deaths on US highways last year, spokespersons of the technology state that self-driven or automated cars will save “time, money and lives”. Things will be simpler and more efficient.

But would they, really?

WHAT IT TAKES

Cars and trucks are increasingly relying on complex computer code to operate. In the past few weeks, automobile companies are promising periodic updates of software systems within cars, so that their features won’t seem outdated.

Driverless cars, in addition to complicated coding, require several cameras and laser-based sensors to read and translate information, then dig into the programming to operate. The maps they rely on are detailed, three-dimensional ones that only map roads, and not all so far. They don’t take into account diversions, and are not precise about puddles or potholes for that matter.

In May, a 40-year-old professional died after his self-driven car crashed into a stationary truck, which its programming failed to take note of. In another test, a self-driven car stopped on the road, as it sensed a black spot ahead. That was a shadow, not a pothole or puddle.

Engineers and programmers are looking to make this better and the way ahead in that direction is more complicated and will need even more sophisticated programming, technology and support systems to be put in place—right from satellite information to the car’s own software and hardware. Simplicity is not its key word.

Efficiency is also under question. With so many cameras and all the hardware required, the vehicle is heavier and more sensitive than other cars. If one system fails, however small the hitch, the user would be helpless.

HUMAN ELEMENT

In 2005, Mumbai was awash with floods. Two young men got locked inside their car, as its electronic central locking, both for doors and windows, failed. Unable to escape as the water filled in, the men died.

Critics of the driverless car, so heavily reliant on complex technology, warn, that climate is one thing the machine, however sophisticated, may not be able to handle.

Apart from systems that may fail under extreme weather, the car cannot decipher the road if the dividing lines are covered with snow or water.

In another incident, in 2009, on a tour in Pakistan, the bus with the Sri Lankan cricket team on board came under terrorist attack. The bus driver Meher Khalil held his nerve through rocket launcher and machine gun fire to drive the team to safety. Driverless cars don’t take into account impediments—even a ball that may bounce suddenly in front of it, or the child who may run behind to collect it.

While we search to perfect that technology, we seem to be dispensing with what indeed can handle it—the human factor. Captain Sully would testify.