India is the biggest arms importer in the world today, having outspent the nearest competitor—Saudi Arabia—by nearly $12 billion last year. Long before this dubious tag stuck, successive governments in New Delhi had tried in vain to make India self-reliant in defence production. Now the Modi government is betting on its ‘Make in India’ initiative to transform the subcontinent into a manufacturing hub, motivating foreign defence majors to come and set up shop in India. Sources in the ministry of defence say the procedure has been “simplified” and that the government will fund 90 per cent development costs to Indian industry, while “reserving projects not exceeding development cost of Rs 10 crore (government funded) and Rs 3 crore (industry funded) for MSMEs”.

The defence ministry has now invited foreign defence companies to join Indian firms as “minority partners” in manufacturing activities. The narrow focus on Russian arms supplies had complicated things in the past for India. But now that New Delhi has recalibrated its strategic prerequisites, India’s acquisition bids for foreign arms are driven by need rather than by ideology. As it looks to win various deals here, the international defence industry will keenly watch the new policy's impact on New Delhi’s approach to procurement.

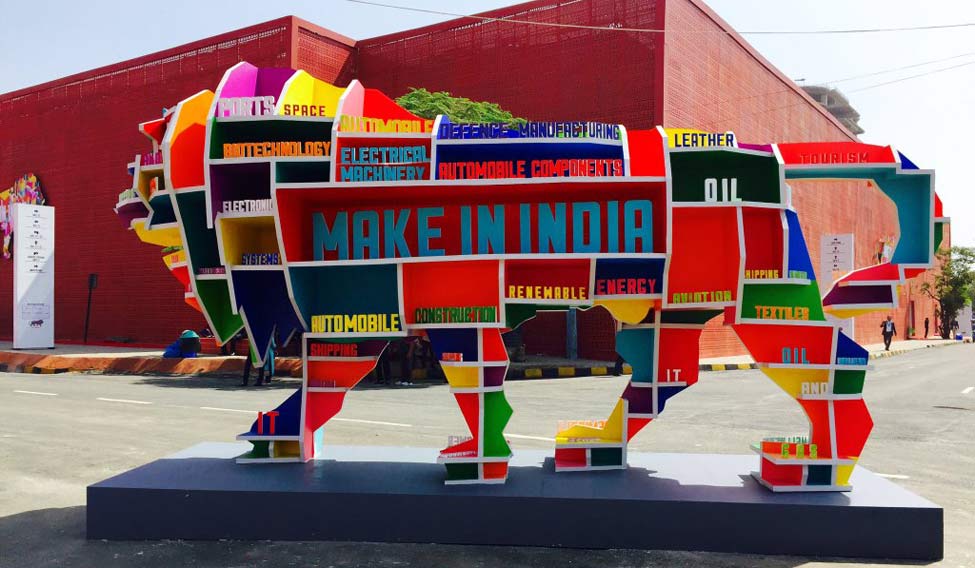

The government believes joint ventures (JVs) will not only help India assimilate cutting edge technology, but also help create thousands of jobs in the country. This makes sense for the Modi administration, which is under pressure to accommodate the legions of youth that join the work force every day. The pressure may only increase as the growth rate of the economy is reportedly slowing and the Goods and services Tax (GST) rollout last month has unsettled businesses across the country. With general elections barely a couple of years away, the government may be looking for quick solutions.

New initiatives to bolster the defence industry such as dramatically increasing FDI in defence, and the surprise appointment of Nirmala Sitharaman—who, as commerce minister, proved her mettle in tough negotiations with foreign governments—indicate Prime Minister Modi’s intention to bite the bullet. But will it be enough to augment the fledgling manufacturing climate and reorganise the muddled defence procurement process (DPP)? The new strategic partnership (SP) model, for instance, selects companies to build military platforms like submarines and fighter jets in India in partnership with foreign majors. But it is yet to be tested and, as a result, ministry sources say some key projects are stuck in the pipeline. The SP model will be put to its real test in the upcoming multi-billion dollar bids for single-engine fighter aircraft and helicopters where Lockheed Martin (US) partners Tata Advanced Systems Ltd and Saab (Sweden) has a JV with the Adani Group. Neither of the Indian firms has experience in building aircraft and it remains to be seen how the JVs take off.

Many observers feel New Delhi should emulate countries whose dynamic defence ecosystems were developed by awarding long-term contracts to a few major companies, and cheerleading smaller local firms to build around them. China, for instance, initially allowed foreign defence firms to develop manufacturing centres in major cities on the condition that they form JVs with Chinese companies. Transfer of technology to the local partners was an intrinsic part of the deal. True, in India, many private sector companies do not need to scale up their capabilities as they have already been supplying spare parts to foreign defence majors. So JVs under the ‘Make in India’ programme could help these companies participate in the design and development of defence hardware as well. But the big question is: can they measure up? Also, foreign firms will need reassurance that delays and controversies plaguing India’s acquisition bids are just bad memories and bureaucratic red tape will no longer hinder their operations.

During Modi’s recent visit to Israel, several defence cooperation compacts were signed, which include Israeli-Indian JVs. US majors and dominant players in the Indian market have won many mega deals in the recent past and are favourites to win several more. A few are in the foreign military sales category—direct government to government sales—while others face stiff competition from international companies. US military spending has increased under President Trump after nose-diving in the aftermath of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. So defence giants like Lockheed Martin Corp, Boeing and Raytheon are eager to corner new deals in the subcontinent. Having made India a ‘major defence partner’, the US is ready to sell F-16 and F/A-18 fighters and even start an F-16 production line under the ‘Make in India’ framework. But the Trump administration’s reluctance to establish manufacturing bases abroad with US technology, at the cost of American jobs, could derail it.

The coming weeks and months will tell if India has finally turned a corner in laying the foundation to a strong defence industrial base with export capabilities.