Fifty years ago this week, the world's first Automatic Teller Machine or ATM was put into service by three European banks, almost simultaneously.

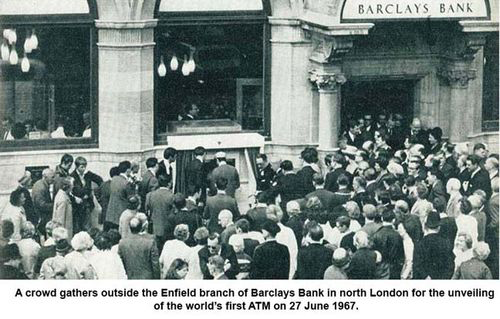

On June 27, 1967, at the Enfield branch of Barclays Bank in London, the world's first customer-operated cash machine was open for business.

It was the brainchild of Scotsman John Shepherd Barron, managing director at banknote manufacturer De La Rue, who was inspired after he arrived at his bank 'one minute too late' to withdraw money. There were already chocolate vending machines everywhere. Why not cash vending machines, he thought-- and turned his idea into a piece of hardware. He got an order for six ATM machines from Barclays, and then another 50.

Barclay's commemorative website today, explains that there were no cards yet. "Customers had to get special vouchers from the bank, which were processed in the same way as cheques and debited to the customer’s account. Each voucher was worth £10 and was valid for six months. Vouchers were issued only to “approved customers”, who were given a six-digit code known only to them and the branch manager. An “unbreakable punch code” of the same numbers would be printed on the vouchers. Customers would sign the voucher and place it in a drawer in the ATM. The machine would then test the “carbon-14” stripe on the voucher, which was a slightly radioactive material. Customers were then asked to enter their code, which was checked against the one on the voucher. If the two matched, the cash was dispensed in £1 notes in another drawer. Those who needed more than £10 could repeat the process with additional vouchers."

This week, Barclays unveiled a golden ATM at the site of that 1967 machine.

Only three days later, on June 30, 1967, a bank in Uppsala, Sweden, launched its own ATM, calling it the Bankomat. And in the first week of July, another British bank—the Westminster Bank (later NatWest and now part of the Royal Bank of Scotland group)—launched its own ATM using technology from safe-maker Chubb & Smith.

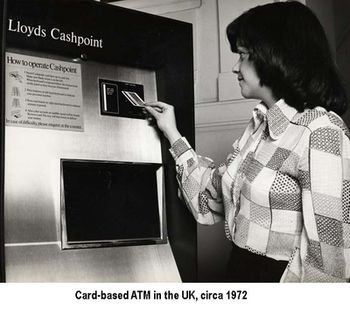

The tipping point came when Britain's largest bank, Lloyds, placed what it called Cashpoints in all its branches and many public places like shopping centres, starting from 1972. Cashpoints worked like ATMs today—with cards.

Close encounters of the financial kind

When I landed in UK a few months later as a postgraduate student, the manager at the Birmingham University branch of Lloyds, opened a checking account for me in two minutes flat. Those were less complicated days—all I need to show him was my ID card issued, not by the University, but by the Students' Union. No 'minimum balance'. No 'two sureties'. The manager gave me a Cashpoint card and simultaneously deposited £5 in my account as an 'enrolling' gift. I stepped out and promptly withdrew £2 from the ATM, to pay for my lunch in the cafeteria next door. It was thrilling for me, who had never seen a cash machine, to draw money, anytime anywhere, without going to a bank. I did not then appreciate that by the accident of being in the UK at the right time, I was among the earliest users of what was to become the greatest self service finance technology of the century.

Back in India after a year, I had to wait another decade and more, to use an ATM. It was introduced by HSBC in 1987 in the Sahar Road branch of Andheri East, Mumbai.

But it was to be another six years before ATMs came to Kerala, where I then worked. The first ATM in Kerala was set up in Velayambalam, Thiruvananthapuram by the British Bank of the Middle East (now HSBC) in 1993, followed by the State Bank of Travancore at Statue junction in 1994 and Centurion Bank in Ernakulam. Among private banks, Citibank soon had the largest Indian ATM network. Way ahead now is State Bank of India with some 60,000 ATMs. The number will go up when the ATMS of affiliate State Banks, now merged, are also added

Today in India, there are over two lakh ATMs. But in a lopsided policy flowing from demonetisation, the government seems to have pressured banks to go slow on growing their ATM network, so that e-cash takes off . In doing this, it hasn't sensed the popular will. Even as the ATM crunch eased around April 2017, e-payment transactions shrunk as people returned with relief to cash.

ATMs will not go away in the foreseeable future—they will morph into new systems that are cardless, contactless—and work with mobile phones.