Former chief election commissioner of India, Navin Chawla, first met Mother Teresa in 1975 at Nirmal Hriday in Delhi. The diminutive figure clad in a white sari with blue border made quite an impression on him with her simplicity, devotion and, above all, love for the poor. It was the beginning of an association which went on till she breathed her last in 1997, and beyond. Chawla had the privilege of penning the official biography of a woman who was loved and venerated around the world by people belonging to different strata of the society. Here are a few excerpts from the book:

When Mother Teresa finally left the Loreto Order and draped herself in the trademark white sari with blue border for the first time

It had to be a secret. Father van Exem, who was her spiritual director, had asked her not to speak about it for a year, to let it mature in her mind as it were. If she still continued to feel the same after the year [1947] was over, it would be real. When news finally came that Mother Teresa was to leave the Order, I felt very happy and said, “Well, it’s a challenge, I hope she will have the health.” ’

Meanwhile, letters went out to every Loreto institution in India. They were asked neither to criticize nor to praise, but only that they should pray for her.

That evening, Mother Teresa came to the sacristy of the Convent Chapel and asked Father van Exem to bless the dress that she would wear from then on. Placed in the sacristy were three white saris with blue borders, and on them a small cross and a rosary*. Father van Exem recalled the scene. ‘Mother Teresa stood behind me. Standing next to her was Mother du Cenacle, her Superior, who was sobbing. I blessed the saris because they would be a religious habit for her.’...

… On 17 August 1948, Mother Teresa wore for the very first time one of the saris that Father van Exem had blessed. Her pupils were especially curious to see her and tried unsuccessfully to get a glimpse of her, but it was already quite dark when she slipped out of the Convent at Entally. ‘The Bengali Teresa’ had started on her ‘little way’.

*The saris she chose were similar to those worn by the sweeperesses of the Calcutta municipality in those days.

How Mother Teresa opened the Motijhil chapter

On the morning of 20 December, according to Father van Exem, she stepped out, for the first time, into the ‘bustee’ of Motijhil.

Motijhil, literally translated, means ‘pearl lake’. It was nothing of the kind. It was actually a largish tank in the middle of the locality. Today, its residents would be outraged if one were to attempt to call their habitation a ‘bustee’. For Motijhil boasts paved roads, electricity, a proper drinking water supply and sewage. The houses may be small, but most of them are well-built. TV aerials sprout from many a roof.

But, in 1948, when Mother Teresa first entered into her work, there was no sign of well-being. The sump was the sole source of water for drinking and washing. Sewage flowed into open drains, and rubbish piled up for days before it was removed. There was no clinic or dispensary. There was no school. It was not unexpected for Mother Teresa to begin her work in Motijhil. It was already a familiar sight from the windows of the classroom block of the Entally Convent. Moreover, the members of the Sodality at St. Mary’s had worked there. Father Henry the parish priest, knew the ‘bustee’ well, and was anxious to help her. It was from him that she obtained the addresses of several poor families who lived there and whose children attended St. Teresa’s parish school.

It was these parents whom Mother Teresa met on the very first day. They were delighted at the prospect of a little school in their midst and promised to send their children to her. That there was neither a building nor even a room available did not deter her. She had no money for even a blackboard or for the slates used commonly by village children to write on with pieces of chalk. On her second morning in Motijhil she found five little children waiting for her. The only open spot was under a tree near the sump. ‘I took a stick and used it as a marker on the ground where the children sat. We began right on the ground,’ she had said.

How Shantinagar changed a taxi driver's perception about the "Lepers' Home"

Initially, the taxi driver was puzzled when we asked to be driven to Shantinagar. In a conversation that involved the use of Bengali, Hindi, English and a great deal of gesticulation, we succeeded in communicating our objective. ‘Why couldn’t you say “Lepers’ Home” in the first place?’ enquired the taxi driver. But surely, he must recall the name ‘Shantinagar’, I asked. After all, he must have ferried several people there over the years. ‘I have only been there once in the last ten years,’ he said. ‘No one in his right mind would wish to visit a lepers’ home.’

Sometime, somewhere that afternoon, Ramu, for that was the taxi driver’s name, changed his mind. Bored in the isolation of his taxi, curiosity and perhaps hunger got the better of him. At first he refused the Sisters’ offer of lunch, probably believing that he might find a small roadside eating house. Finding none in the immediate vicinity, he finally went into the kitchen, where the Sisters fed him as generously as they had fed us immediately upon our arrival, parboiled rice of the cheapest kind found in Bengal, some dal and a little salad. There was fish, too, fresh from the lake, which Ramu admitted was delicious. He confessed that his family and friends would be appalled to know that he had visited, let alone eaten, in a leprosy institution, but that afternoon he had learnt an elementary lesson: that leprosy is easily curable if detected early, and that contagion is no longer a dread.

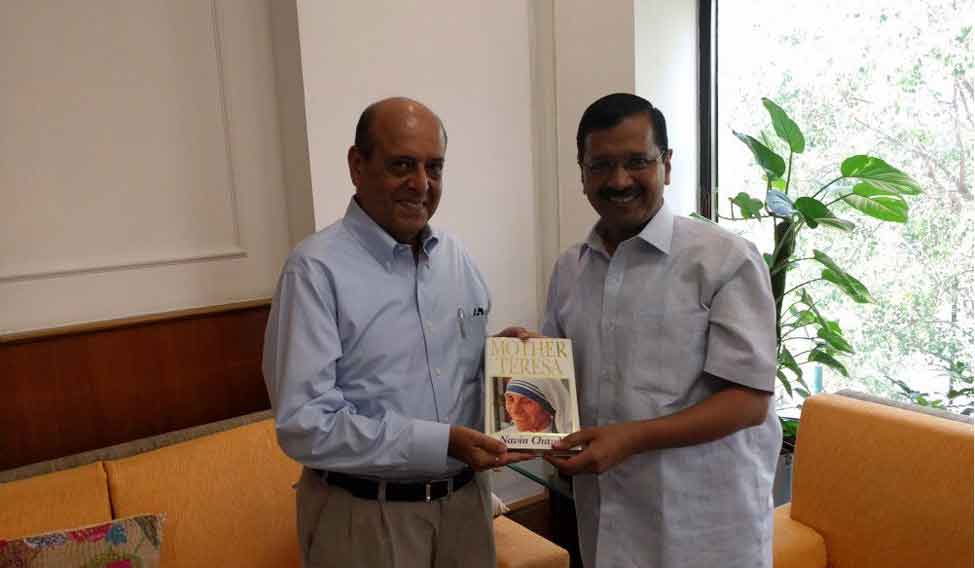

Navin Chawla presents a copy of the book signed by Mother Teresa to Arvind Kejriwal. The Delhi chief minister has worked at her Kalighat ashram for two months in 1992 | Source: Twitter

Navin Chawla presents a copy of the book signed by Mother Teresa to Arvind Kejriwal. The Delhi chief minister has worked at her Kalighat ashram for two months in 1992 | Source: Twitter

When Pope Paul VI was touched by the work of Missionaries of Charity

Then a ‘miracle’ occurred. Pope Paul VI visited Bombay to participate in the International Eucharistic Congress in 1964. For his visit, a custom-built Lincoln Continental limousine was flown out for his use as a gift from the American people. He rode in it to bless the multitudes of the faithful; it also carried him on his pilgrimage to Mother Teresa’s Home for the Dying in Bombay.

So touched was he by the work of the Missionaries of Charity which he witnessed that, before leaving India, he gave the limousine to Mother Teresa. Nothing if not practical, Mother Teresa promptly raffled it, and obtained far more money than she would have had she advertised its sale through newspapers, such was the publicity that the event attracted. The money she received went towards the building of the main hospital block in Shantinagar.

How Mother Teresa overcame the opposition to Nirmal Hriday in Kalighat

The idea of a place for the dying, so close to a venerated Hindu shrine, upset the temple priests. Furthermore, the Brahmin priests were shocked that the precincts of the Kali temple had been handed over to a Christian missionary. They petitioned the municipal authorities several times to discontinue the arrangement. These petitions remained unattended.

Then one day, a strange incident occurred that brought opposition to an end. A young temple priest, not quite thirty, began to vomit blood. He was diagnosed to be in an advanced stage of tuberculosis, and no hospital was prepared to admit such a hopeless case as it would mean depriving a curable patient of a bed. Sick in body and heart, the priest was finally brought to Nirmal Hriday.

Mother Teresa gave him a special corner to himself, where she nursed him. He was angry and felt humiliated, but with each passing day, he slowly began to accept his situation. By the time he died, rage had given way to tranquillity.

Meanwhile, the temple priests, who had been unable, or unwilling, to help their brother, observed the care that he received. Nor did they fail to notice that when he died, far from being given a Christian burial. Mother Teresa sent his body to be cremated by Hindu rites.

Mother Teresa on how her work has changed Calcutta

The prayers are over. The last of the worshippers has left. It is dusk. Mother Teresa joins me on the little bench on the bridge outside the chapel. I ask her what changes she believes her work has brought to the people of her adopted city.

‘We have come a long way,’ she replied. ‘The people of Calcutta have come to know and love the poor. No one is left to die on the road. Someone, somewhere will pick up the man and bring him to us. I have seen children pick up and take old people from the street to Kalighat. People of all faiths come to share in the work. They say, “Mother Teresa, we want to help.” They are willing to touch the poor, no? That is the beauty of the work. It is the same everywhere else.’

Her work had expanded throughout the world, and yet it was difficult to imagine her belonging anywhere other than Calcutta. Her life and that of the city came to be inextricably bound, one nurturing the other, each strangely incomplete without the other. Millions around the world knew her as ‘Mother Teresa of Calcutta’. It is almost as if it were a tide. For the people of Calcutta, she was one of its presiding deities, certainly its conscience keeper. The former Governor of West Bengal Dr Nurul Hasan once told me that whenever he met Mother Teresa, he asked himself, ‘What have I done to serve humanity?’ Like thousands of others, he too felt humbled by her presence.

It is no wonder, then, that the people of the state called her the ‘Mother of Bengal’.

(Excerpted with permission from Penguin Books India)