Bishnu Deka runs a travel agency in Guwahati. His company did not have any vehicles and rented cars were eating into its profit margins. Once Deka bumped into an advertisement of the tourism department which offered a subsidy on commercial vehicles. He applied and received an offer of $3 lakh. It was, however, not enough to purchase the vehicle he needed for his business. He approached every bank in the city, but in vain. Then he approached Mahindra Finance, a non-banking financial company (NBFC). The very next day, a team from Mahindra Finance visited his home and explained to him the terms and conditions, and his monthly instalments. The loan was approved in an hour and the vehicle was delivered the next day.

Deka's life took a dramatic turn after acquiring the vehicle. His profit grew and he got two more vehicles with the help of Mahindra Finance. Soon he launched radio taxi service, one of the first in the northeast. “After I explained my business plan to the Mahindra Finance people, they helped me finance ten vehicles for the taxi service and today I am happy with my business,” said Deka.

Deka is one of the lakhs of people whose lives have been changed by NBFCs. And, encouraged by the good business, these companies are fast improving their reach and launching products that target semi-rural and rural areas. They have become the automatic choice of people who were denied bank loans. Take, for instance, the case of Inder Singh of Jamsedpura in Rajgarh, Madhya Pradesh. He used to work as a driver and owned 1.5 bighas. The income, however, was not enough to support his family. “I was not able to save a single penny,” he said. It was then he met an employee of an NBFC.

“I wanted to buy an earthmover with a construction equipment loan, but I did not have any proof of income. The representative understood my problem, and was willing to give a loan to me if I could pay a certain amount as margin money. Since I did not have the funds for it at that time, he suggested that I take the loan through a close friend or family member. When I pay the margin money amount, I would be able to transfer the loan and the vehicle to my name,” said Singh.

This worked as Singh began earning regularly from his earthmover. “I sold my land to pay the margin money. Though the NBFC had no physical proof or guarantee that I could earn enough and repay the loan, they agreed to sanction a loan in my name. They judged me on the basis of my ability and willingness to work. I worked hard and was able to repay all my loans. Today, I own an earthmover, a tractor and a jeep, and I am planning to expand my business,” he said.

NBFCs score on many aspects over banks. They have relaxed eligibility criteria and documentation. Over the years, they have created a place for themselves in a market dominated by banking giants. Today, they reach to crores of unbanked Indians, who were vulnerable to loan sharks, and have introduced them to the regulated financial system.

Over the year, NBFCs have built a strong and wide network in the underserved areas. In fact, many of them did not wait for a branch to open up in a particular area, and offered mobile branches at the customers doorsteps. “Low penetration of banking services, the ability of NBFCs to create products that are relatively simple and easy to distribute and focus on specific segments of the economy as well as relative ease of entry and exit are the primary drivers for this industry. Many NBFCs have also put in place good governance systems and use technology to create transparent and reliable systems,” said Shinjini Kumar, leader of banking and capital markets at PricewaterhouseCoopers India. Last year, the Reserve Bank of India reported NBFC assets of Rs17,140.55 billion.

“There is a lot of credit demand in the country, and, despite the banking structure, NBFCs are growing and trying to carve a niche for themselves in this market,” said Rashesh Shah, chairman and CEO, Edelweiss Group. He attributes NBFCs' success to their innovative and unique offerings. “For instance, our credit business offers five broad products, including mortgages, structured collateralised credit to corporates, distressed assets credit, SME and agri financing, loan against securities, and rural finance and other loans.”

While wholesale credit products offered by NBFCs cater to niche markets, retail segment loans help scale up business in the untapped markets. Many of these companies are trying to distinguish themselves in the crowded market by providing specialised offerings, minimal paperwork and faster loan approvals.

Shinjini Kumar

Shinjini Kumar

The multinational lender Fullerton India, for instance, has focused on the last mile reach ever since it started the Indian operations in 2007. With the use of advanced technology, understanding of risk, simplified processes and faster turnaround time, the company has been able to provide its financial services facilities at the doorsteps of customers. Each rural branch of the company caters to a radius of 30km, enabling its representatives to cover over 42,000 villages.

“We are offering our customers customised products and catering to their special needs, which helps increase their trust in us,” said Rakesh Makkar, executive vice president and head of business and marketing, Fullerton India. “We also take care of providing the rural customer with a simple and welcoming environment. Also, we hire from the local talent pool to bridge cultural, regional and language differences.”

Many of these NBFCs do not stop at just offering financial services. Fullerton, for instance, has social reach-out programmes. “Since many of our villagers are dependent on animal husbandry, we have been conducting regular cattle care camps to help them increase the yield,” said Makkar. The company invested heavily in technology by adding applications and tools in the past two years. “Given the extensive customer base, we are delivering more and more IT-led initiatives and are digitising our processes,” he said.

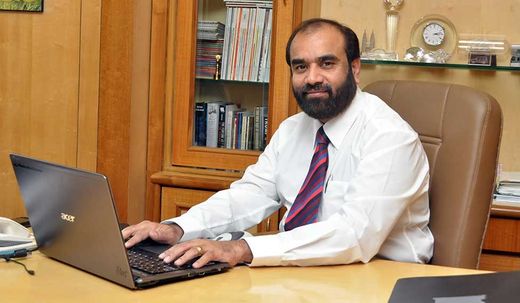

Ramesh Iyer

Ramesh Iyer

Digitisation has been a game-changer for NBFCs. Now these companies blend digital and physical resources for innovation and to achieve operational excellence. “We have online channels, machines equipped with digital sensors, agile design and frontline teams equipped with smart phones and tablets for customer interactions, and cloud-based software. We will use digitisation to increase revenue and drive operational excellence agenda in real time,” said Makkar.

Realising that a larger footprint, especially in the semi-urban and rural areas, is key to their business, NBFCs have gone into overdrive to improve their reach. “Over the past 20 years, we have penetrated deeper into the rural market with around 1,200 branches covering customers in more than two lakh villages,” said Ramesh Iyer, managing director and president (financial services), Mahindra and Mahindra Ltd. “In order to understand the customer requirements, we have recruited people from local colleges.”

In fact, a better understanding of customers is the cornerstone of most strategies applied by NBFCs. “It is extremely important to understand customers' requirements and partner them,” said Iyer. The customers' cash flows in rural market depend on various factors. We have had several situations in the past where the customer had not been able to service loans on time in view of lower cash flows and our approach had always been one of partnership. We have also designed products based on customer cash flows rather than standardised products that might not suit the customer requirements. Our entire lending process and product design is based on understanding of customer earnings.”

Interestingly, the back-up documents for credit decision often fail to give the precise knowledge of customer cash flow. That is why Mahindra Finance has trained its field executives to understand income flow from different activities and developed an internal matrix for making credit decisions. “Our lending is interactive-based,” said Iyer.

Similarly, Muthoot Finance, India's largest gold loan company, has thoroughly institutionalised gold loan processing. “We have built clusters and have 68 regional offices across the country. The gold loans are processed within a few minutes unlike a bank which takes a few hours to a day to process a gold loan.We have the capability to check the purity of gold quickly and to keep it safely. We have trained people to do the whole process,” said K.R. Bijimon, chief general manager, Muthoot Finance.

Muthoot has around 4,300 branches across India. “We do not have franchise models and since it is the gold loan business we want to have full control over all the branches. We have employed locals in our branches who can interact with the local people better and understand their requirements,” said Bijimon. More than 70 per cent of Muthoot's branches are in rural and semi-urban areas. The company also offers housing and vehicle laons.

Rashesh Shah

Rashesh Shah

Despite the growth and the huge market, NBFCs face many challenges. The biggest of them is the high cost of funds. But experts say strong players will overcome this by accessing equity and debt markets on the back of their growth potential, management strength and good track record. Large NBFCs that focus on infrastructure have access to cheaper external commercial borrowing.

And, there is this constant fight against discrimination. “There is an inherent policy bias against NBFCs as they are often seen as shadow banks, that have a 'light touch' regulation and are able to charge high rates of interest due to lack of access to many sectors or client segments,” said Kumar of PwC India.

The rural Indian market is still cash-driven and most customers like to repay their instalments in cash, rather than via banks. When it comes to NBFCs, they expect the lender to collect instalments at their homes and understand the reasons for default rather than taking standardised decisions. NBFCs meet this challenge employing a large field force and offering different repayment facilities to their customers. Some companies even offer part-payment facilities based on customer cash flow.

Experts say NBFCs have an important role to play in expanding the market for farm vehicles, tractors and pre-owned vehicles. “NBFCs will play a very important role in the SME sector and the housing segment given the initiatives of the government in infrastructure, manufacturing, housing and development of smart cities,” said Iyer.

The future of NBFCs in India, to a large extent, will depend on bank licensing and consolidation policies. “If many small banks get licences, they will compete with NBFCs, presumably with a lower cost of funds. However, small banks will lose the advantage of specialisation as banking regulations are focused around diversity of portfolio and a prescriptive priority sector loan portfolio. In that sense, unless banks are given much more flexibility in terms of entry, exit, consolidation and operations, NBFCs will continue to find their niche. However, long-term growth path for really large NBFCs may gradually become more challenging if banks are able to create distribution models that are low-cost and customer-friendly,” said Kumar.

Two recent developments might make the future of NBFCs in India is bright—the guidelines released by the Reserve Bank in November 2014 to create a level playing field among the financial institutions and the announcement for NBFCs to use the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act in the Union budget. The budget proposal to treat non-banking financial companies as financial institutions under the SARFAESI Act had been the industry's long-standing demand and will allow NBFCs to enjoy the benefits that presently apply only to banks. The move is broadly aimed at bringing parity in regulation for NBFCs with other financial institutions in matters relating to recovery. The move will be applicable to all NBFCs registered with the RBI.