A hush fell over the room just before the arrival of the maharaja of Jodhpur, Gaj Singh II, a man whom many affectionately refer to as Baapshi— father— in his native Rajasthan. He entered with a subtle smile to his coterie, wearing a gray Nehru jacket with ruby and emerald-encrusted buttons, his salt-and-pepper hair and paintbrush mustache neatly combed.

Polite greetings—“Good evening, your Highness”—were murmured with a touch of reverence as the maharaja inspected the room’s installation: Bleu de Jodhpur, this year’s haute jewellery collection from Boucheron. It was born of a collaboration between the maharaja and the house’s creative director, Claire Choisne.

Choisne, in a leopard print Gucci dress and hovering around six feet tall in her customary spike heels, swooped in behind the maharaja and playfully squeezed his shoulder as she mugged for the cameras, her face incandescent, his, amused. “He is so friendly,” Choisne said later, “that you forget what his position means.”

The two first met a year and a half before, during Choisne’s visit to the maharaja’s ‘blue city’ of Jodhpur, a place that enchanted her with its indigo-washed, cube-shaped houses, its colossal Mehrangarh Fort—a 15th-century sandstone citadel that sits high above Jodhpur on a desert cliff—and the Indo-Art Deco splendour of the Jazz Age Umaid Bhawan Palace, where the maharaja lives and received the designer.

“We shared the same desire to create a modern collection with a modern vision of Jodhpur,” Choisne recalled. The maharaja is no stranger to jewellery: They discussed jewellery ideas and the rich culture of his region. “I organised for Claire to see things to get the feel of Jodhpur; one of the Sufi festivals with the dervishes, and the festival of colours,” he said. “She saw the palace and the blue houses of the old city, she saw so many things. She didn’t know what hit her!” The maharaja said Choisne wanted to use materials that had a physical connection to Jodhpur, so he prodded her to order veinless, milky Makrana marble from the local quarries that supplied the builders of the Taj Mahal in 1631.

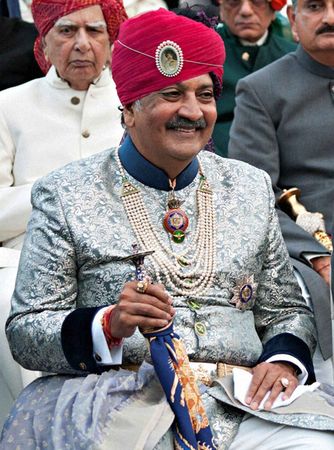

Royal touch: Gaj Singh II, the Maharaja ofJodhpur | PTI

Royal touch: Gaj Singh II, the Maharaja ofJodhpur | PTI

The result, the Plume de Paon necklace, was the first use of marble in haute jewellery and, Choisne said, the collection’s greatest technical challenge. “The Plume de Paon necklace is a paradox,” she said. “It’s a feather, a feather is light, but it’s made of marble and marble is hard, marble is heavy, but cut so thin, it becomes light.” The necklace sells for more than 1 million euros, as do many of the largest of the 100 designs in the Bleu de Jodhpur collection. Prices start at Rs.35 lakh approx.

The Nagaur necklace also used an unexpected material: sand from the Thar desert that surrounds the medieval Mehrangarh Fort, captured in a transparent rock crystal pendant shaped to echo the fort’s geometry.

“Claire brings a flat design up here to us, and we make the composition feasible, no matter what it is,” said one of the goldsmiths in the upstairs atelier, where 13 artisans create Boucheron’s haute jewellery. “We make it wearable, comfortable, we give it volume, we make it real.”

When Choisne, then 35, was appointed creative director at Boucheron in September 2011, she had only a week’s time to invent a collection for the house’s return to the Biennale des Antiquaires, the pre-eminent event in haute joaillerie. Was it intimidating?

Having spent a decade as studio manager for Lorenz Bäumer, where she produced collections for many of the Place Vendôme jewellery brands, she was, in her words, “entreiné”—in shape—ready to create quickly and confidently.

“Now I have one brand to focus on, I have all of the archives, I have the pleasure to work directly with the craftsmen,” the Paris-born designer said, clapping her hands together and grinning.

Boucheron, in business since 1858, is one of the last jewellers on the Place Vendôme to have an in-house atelier. It was also the first to set up shop there, in 1893, a few years after Frédéric Boucheron invented his groundbreaking “question mark” necklace—an open, asymmetrical collar, now incorporated into many of Choisne’s designs, including the Plume de Paon.

Her approach, “the rebirth of the archives” as she calls it, revisits many early Boucheron concepts—like the rock crystal she uses in every haute jewellery collection. “This material gives you a lot of creative freedom to play with the transparency,” she said.

She pulled out the design for the reversible Jodhpur necklace, a majestic plastron that took 1,700 hours to fabricate, with linear Makrana marble and diamond drops on one side, and on the opposite, a classic Indian floral motif in sapphires that seems to float on rock crystal.

Placing the design side by side with the archive illustration of the traditional Indian necklace that inspired it, Choisne explained, “You can see the plastron shape, the tassel and the cord. I kept these from the past, added marble and made it reversible.”

The inspiration necklace is one among 149 designs that Boucheron created for the maharaja of Patiala in 1928. “That order is legendary at Place Vendôme,” according to Vincent Meylan, author of Boucheron: The Secret Archives. “He was very famous because he was two metres tall, he was obscenely wealthy and he was crazy about sex and precious stones,” Meylan continued. “One day, he arrived at Boucheron from the Ritz with all these caskets of stones”—an astonishing 566 carats of diamonds and 7,800 carats of emeralds—“and ordered them all turned into jewellery for himself. Back then, the biggest jewellery was worn by the men.”

Palace on wheels: Gaj Singh II drives a vintage car during a photo shoot for a vintage car rally | PTI

Palace on wheels: Gaj Singh II drives a vintage car during a photo shoot for a vintage car rally | PTI

Said Choisne: “I always wanted to do something with the Patiala designs. And then in Jodhpur I met the maharaja, and I had such a traditional image in my head, but he was so modern.”

Born in 1948, the maharaja, now 67, has positioned himself as a modernising force in Jodhpur.

“When I came home from university in my 20s, whatever remaining privileges we had were taken away by the government,” the maharaja said, referring to the 1971 abolition of the titles, lands and state salaries of princely India. “I felt the need to stay connected, with the people, with the culture, with one’s history, with one’s own land.”

He has since revolutionised the role of a maharaja, casting himself as a cultural ambassador for Jodhpur and an activist in the preservation of the region’s cultural treasures. He transformed his Umaid Bhawan Palace into a luxury hotel to attract tourism and turned the Mehrangarh Fort into a museum and research centre.

He created a host of festivals, including the Sufi festival that Choisne visited. Recently, he organised an international exhibition of 18th- and 19th-century paintings from Jodhpur, which inspired Choisne to create a “Garden and Cosmos” chapter for Boucheron’s collection, featuring the Fleur de Lotus necklace with a stylised sapphire, rubellite, diamond and marble flower springing from the tip of the pioneering question mark collar.

“When you look at the first pieces of Frédéric Boucheron, he developed such creative techniques, like the question mark necklace,” Choisne said. “So we have to keep the spirit, we have to create emotion.”

Over the few July days in which the Bleu de Jodhpur collection was viewed, “Ooh!” and “Très jolie!” was the chorus as visitors glimpsed the jewels for the first time.

But the greatest compliment came from the man involved in their creation. “They really understood my city,” said the maharaja, who, after viewing the collection, ascended the stairs to thank each of the atelier’s artisans personally.