J.A. Gemmell was a senior corporate executive in Calcutta. Like hundreds of other English citizens, he left India in the 1940s when the Independence struggle was at its peak. In 1994, Gemmell died in the United Kingdom, 11,000km from Calcutta, where he left behind bank accounts in Standard Chartered Bank and shares in New Birbhum Coal Co Ltd and Naihati Jute Mills Co Ltd. Then, his Indian estate’s worth was approximately Rs35 lakh.

But neither Gemmell’s family nor his executors, the National Westminster Bank, had any clue of his Indian assets. Enter Rakesh Gujral, 46, crusader of lost assets. Tall, thin and wearing a T-shirt and slacks, Gujral looks anything but a crusader. Over the past ten years, he has been patiently tracing families with old assets in Indian companies. He approached the National Westminster Bank in 2008 and prodded them to dig out Gemmell’s will, which was executed in the 1970s. While there was a fleeting mention of Indian investments, the will threw no light on other details. But Gujral’s meticulous research found the names of Standard Chartered Bank, New Birbhum Coal Co Ltd and Naihati Jute Mills Co Ltd. Armed with a power of attorney, Gujral approached the district court for a succession certificate. Soon, he was able to administer the estate and remit the proceeds.

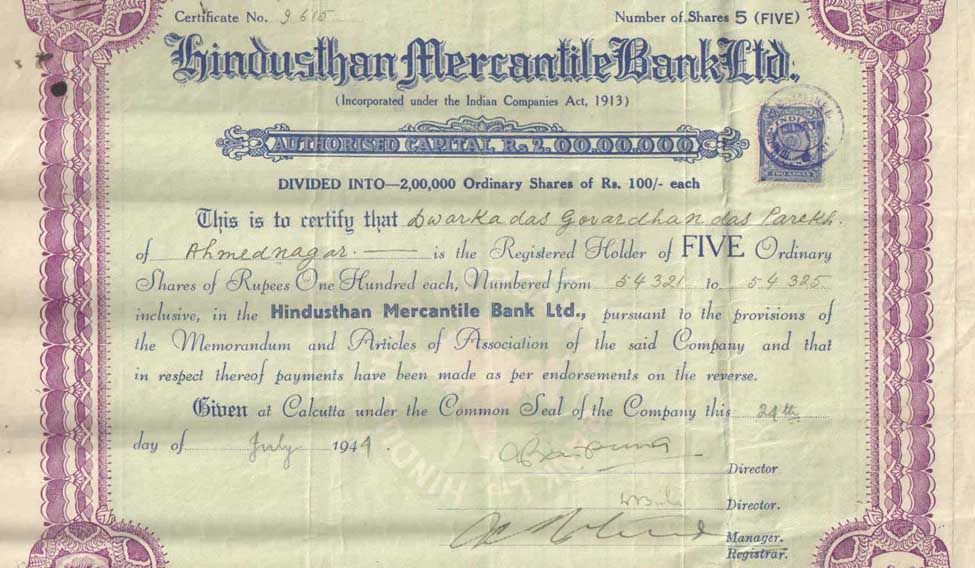

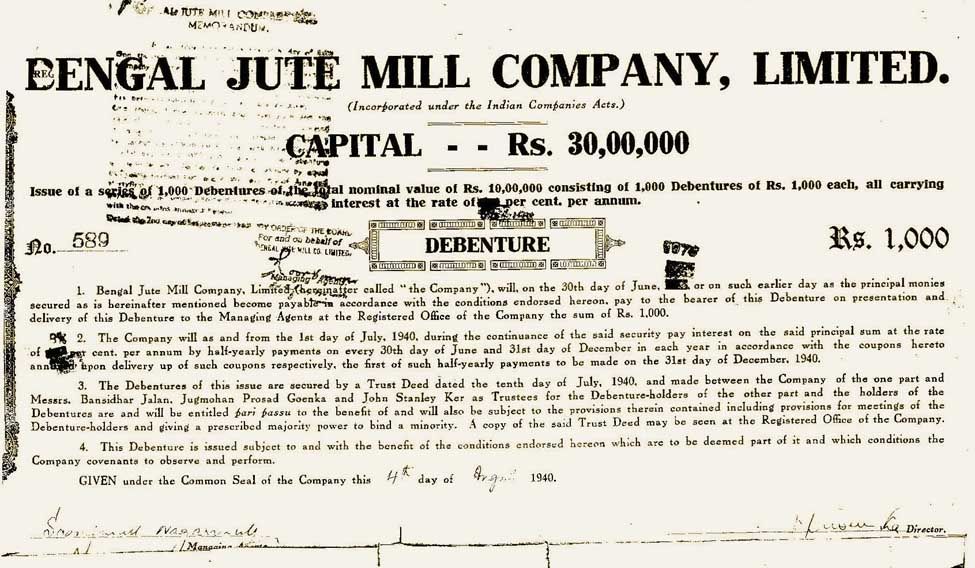

This is just one of the cases where Gujral played saviour. In the past decade, he has helped people from Nepal, the UK and the US besides India trace long-lost assets. His vocation, however, was rather unplanned. A law graduate from Delhi University, Gujral was on one of his many trips to Kathmandu in the late 1990s when a card game of teen patti changed his life forever. Bored of watching his friends play, he picked up an old booklet being used to keep score. It turned out to be the annual report of a jute company from the 1930s. His interest aroused, Gujral rummaged his friend’s storeroom and unearthed scores of yellowing, decrepit share certificates from ramshackle metal trunks. These records belonged to the extended Rana family of Nepal and mentioned the Mercantile Bank of India (presently HSBC Bank), Imperial Bank of India (presently State Bank of India) and bills from Tata Steel.

“I spent days going through old records, preparing a list of the companies named therein. I knew a few were in existence but I had no clue about many of the others,” says Gujral. He visited company offices throughout India looking through their annals and examining the records of the registrar of companies. “I had to answer the question―did these companies exist. And if they did, were the investments still there? The search had to be manual as this was when Google was not popular in India,” he says.

He zeroed in on 30 companies that still existed and started corresponding with them. A few confirmed that there was shareholding in the name of the deceased. “We had to get a succession certificate from relevant district courts in India. In 2005, after following various company procedures, the share certificates finally came in from 15 companies,” says Gujral.

It took him two and a half years to help the family retrieve unclaimed assets and, before long, he was flooded with similar requests from other Nepalese citizens with shares in Indian companies. “Another friend from Kathmandu and belonging to the Rana family approached me. He had certificates of Chinese loans, Japanese loans and French rente [loans],” says Gujral. But these loans had already been written off and Gujral ended up successfully liquidating other share certificates from existing companies. And what started off as just an interest soon laid the foundation for Fundtracers, Gujral’s Delhi-based company set up in 2006.

While researching the records of companies, Gujral also found that some shareholder names were recurrent. “There were names from Sri Lanka, South Africa, Malaysia, Europe and the US. I realised this is not limited to Nepal alone,” says Gujral. He created a database of people who invested in companies in India before the 1960s. He then started seeking them out one by one. That is how he ended up helping Ludhiana’s Sama family retrieve Rs22 lakh and H.C. Allen’s family in Scotland claim Rs45 lakh.

But how do people forget about investments and assets? British investors, for instance, lost their assets when they left India. Records were mostly lost when the person died and, sometimes, changes in address were not communicated to the companies.

Gujral works with three lawyers, a chartered accountant and a couple of researchers. His primary source of income, however, comes from the stock exchange. He does what he does for the love of tracing unclaimed assets. “The fee varies from case to case. The understanding is that I will take care of India-specific expenses including travel, court expenses, company expenses and newspaper advertisements. Everything outside of India is the client’s responsibility,” says Gujral. Courts, for example, demand a surety to reward the succession certificate. Gujral provides his own fixed deposit as court surety when his clients are foreigners.

Right now, Gujral is busy ferrying relief material to his second home, Nepal, destroyed by the recent earthquake. Once back, he will track members of the royal family of Darbhanga in Bihar. “I have travelled to Purnea, Katihar and Darbhanga but have not managed to find them till now,” says Gujral. He will try once again before moving on to the next name on his list.

.jpg.image.234.136.jpg)