The Union health ministry's ban on 344 fixed dose combination drugs has left Lakshmi Prabha, 44, of Delhi worried. All these years Saridon, which has been banned, was her magic pill for migraine. But now, she wonders whether it was silently taking a toll on her health.

“I wonder if my most reliable medicine has already damaged my system,” says Prabha, who works with an insurance company. “Was it really so bad?”

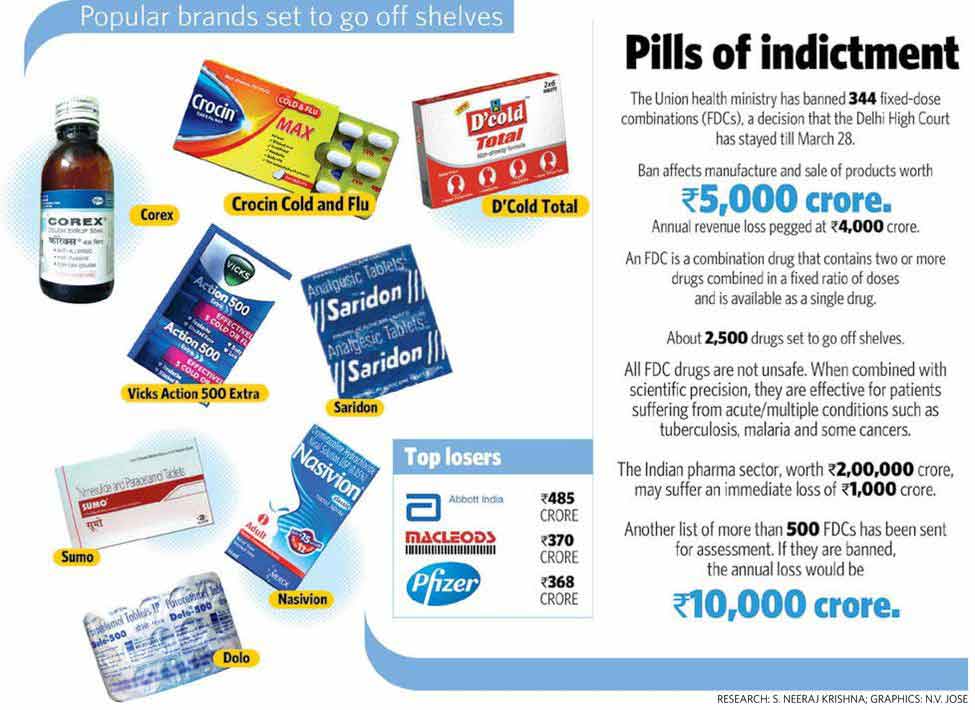

Piramal Healthcare's Saridon—a combination of paracetamol, caffeine and propyphenazone—is not the only popular brand that has been banned. And Prabha is not the only one flummoxed. FDCs for common cold, flu, pain, diabetes, hypertension, cholesterol and a few antibiotics also are on the list. Several cough syrups, too, have been banned.

Talk of cough syrups, and Shema Suresh, 45, raises her eyebrows. Whenever she has a slight throat discomfort, she buys a bottle of Corex or Glycodine or Benadryl. Now that it is being said that these syrups are harmful, she is perturbed.

“It is true that I feel a little drowsy after taking them. But I have been taking these syrups for years and, so far, I have not had any problem,” says Suresh, who also works with an insurance company. “I would like to know in detail what these combinations can do to one. Also, how could the government allow these [allegedly] unsafe medicines to enter the market?”

The government says these FDC drugs pose a “risk” to consumers, and safer alternatives are available. (The Delhi High Court, however, has given interim relief to pharma companies by staying the ban till March 28.)

The government’s decision came after an expert committee headed by Dr Chandrakant Kokate, vice chancellor of KLE University, Belgaum, found 344 FDCs unsafe. Many of them are banned in the west.

Some popular drugs affected by the ban are Pfizer's Corex cough syrup, P&G's Vicks Action 500 Extra, Glaxo's Piriton expectorant, Reckitt's D'Cold, Glenmark's Ascoril and Alex cough syrups, Abbott's Phensedyl cough syrup and Alembic's Glycodin cough syrup.

Incidentally, a Central expert committee is analysing another list of over 500 FDC drugs. More bans are likely.

Shema Suresh

Shema Suresh

Pharma companies say the sudden ban would result in a loss of thousands of crores. The health ministry says the companies were asked to prove the safety of their products, but they failed to convince the expert committee.

FDC drugs have two or more medicinal molecules combined. The Central Drug Standard Control Organisation has to assess every FDC like a new drug, as bringing different molecules together may alter their functioning and the composite drug could have undesired effects on the body.

“Giving licence to a drug is a rigorous process with many phases of clinical trials,” says a health ministry official. “Pharma companies bypass the Centre and acquire licences from state drug authorities, which may not have adequate expertise.”

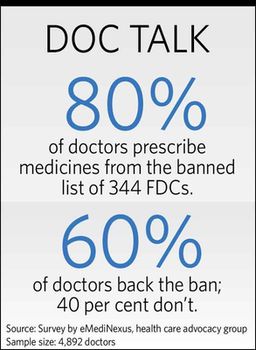

Majority of doctors support the ban. They say, at times, two compounds present in one drug interfere with the working of each other, and that could lead to formation of toxins in the body. Also, a molecule could prevent activation of another, rendering the drug ineffective.

There could be other problems as well. For example, injudicious use of a concoction of antibiotics could lead to antibiotic resistance. It is also difficult for doctors to identify side-effects of each component in FDC drugs. And since these drugs have a fixed dose, adjusting the dosage based on the patient’s requirement is not possible.

Not that all FDC drugs are unsafe. When combined with scientific precision, they are effective for patients suffering from acute/multiple conditions.

“A patient suffering from tuberculosis generally requires at least four drugs,” says Dr Vasan Sambandamurthy, a Bengaluru-based drug researcher. “In the absence of compliance to the four drugs, the patient is at the risk of developing (and spreading) drug-resistant tuberculosis. Here, a combination drug ensures compliance and makes it easier for the patient, as he has to take fewer tablets. Similarly, there are some effective FDC drugs for some cancers, malaria and viral or bacterial infections. In some cases, FDC drugs could cut treatment cost.”

What is needed is a stringent screening mechanism. But, in India, the system of scientific study of the safety and efficacy of drugs has many gaps.

Lakshmi Prabha

Lakshmi Prabha

In 2012, a parliamentary report highlighted that many drug approvals were granted without proper clinical trials. Soon, the Drug Controller General of India formed an expert committee headed by late Prof Ranjit Roy Chaudhury to overhaul the drug regulatory system.

The committee submitted a 100-page report in 2013. It noted that as many as 85,000 formulations had to be reassessed. Notably, a 2010 study by the Community Development Medicinal Unit and the NGO Health Action International said 1,356 irrational FDCs were marketed under 4,559 brand names.

Citing an example from the current list of banned FDCs, Dr R.K. Singhal, chairman, internal medicine, BLK Hospital, Delhi, says that a combination of nimesulide (an analgesic) and serratiopeptidase (an enzyme) is irrational. The enzyme should be given 30 minutes before food and the analgesic 30 minutes after!

Says endocrinologist S.K. Wangnoo of Indraprastha Apollo Hospital: “I never prescribe FDC drugs. In metabolic disorders such as diabetes, a doctor needs to the decide on time and dosage of a single drug depending on the patient’s requirement, which is not possible with FDCs.”

Indian guidelines advocate diet and exercise and a single medicine (metformin) to control diabetes. However, a 2013 study published in The Lancet noted that sales of metformin FDCs were much higher than plain metformin.

Doctors cannot go into details of each and every drug combination available in the market, says Singhal. “It is the regulatory body's duty,” he says. “Though doctors would outrightly reject absurd FDCs, some may make it to the prescription, especially if they belong to reputable brands.”

Pharma giants, however, defend their medicines. Kedar Rajadnye, COO, consumer products, Piramal Healthcare, says: “The drug [Saridon] has been available in more than 40 countries since 1981. We have the highest level of responsibility towards the health and safety of consumers. We will study the government's reply to be filed by March 28, and represent our case to the High Court.”

Until convincing answers emerge, the anxiety of patients—the biggest stakeholders in the matter—would continue.

A REMEDIAL ACTION

By Dr Anoop Misra

Twenty years ago, when I was working at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, I was called to the office of the Drug Controller General of India. There was a panic situation. A popular drug for abdominal pain (a fixed-dose combination of three drugs) was about to be banned, but the High Court had put a stay on it, asking for further proof on whether all three drugs were needed, or only one of them was equally effective.

I was asked to do a clinical trial to resolve the issue. The trial proved that the effect of one drug was similar to the effect of all three drugs in treating abdominal pain. The court ordered in favour of the ban.

Was it a lesson for pharma companies not to make irrational FDCs? Yes. Did they learn the lesson? No. More FDCs followed. Also, the quality of many FDCs was questionable.

Why do physicians prefer FDCs? Because it is easy to give more medicines in a single tablet. This is something I have never done, unless a drug combo is synergistic. (Addition of two drugs in a single tablet results in therapeutic effects which are more than the individual effects of each drug; that is, 2+2=5, instead of 4, in terms of therapeutic effects.)

Giving each drug separately allows me to change dosages, and to monitor adverse effects in a better manner. Also, each drug has different positioning as regards to meals and time of the day. Giving all in one tablet does not allow me to prescribe them appropriately. So this major ban on FDCs has not affected my practice.

Would patients be affected? Yes, in a way. They tend to stop medications if there are too many tablets. On the other hand, patients may ascribe betterment of their symptoms or adverse effects accurately with the use of drugs taken individually.

I believe that this action of controlling FDCs is scientifically correct and should be vigorously pursued.

Misra is chairman, Fortis-CDOC Centre of Excellence for Diabetes, Metabolic Diseases and Endocrinology