When the Central Depository Services Ltd hit the capital markets in June 2017, it was hoping to raise about Rs 520 crore. But the investors were so excited about the initial public offering that it received bids worth almost Rs 64,000 crore—170 times the actual number of shares on offer.

CDSL's was the most subscribed initial share sale in more than a decade, but it was not a flash in the pan. Many companies that went public in 2017 saw unprecedented investor interest. The IPO of Capacit'e Infraprojects was subscribed 182 times, MAS Financial Services IPO 128 times, Dixon Technologies IPO 117 times and D-Mart IPO 105 times the total shares on offer.

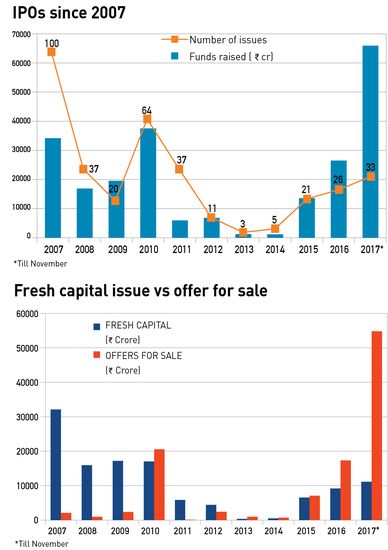

It was a record year in terms of total funds raised via capital market listing. Till November, there were 33 public share offerings that raised a total of Rs 65,923.12 crore, says an analysis by Prime Database. It was higher than the total funds raised between 2011 and 2016. Also, there were 119 IPOs of small and medium enterprises, raising Rs 1,500.90 crore, in the year. The previous best year for IPOs was 2010, when 64 companies raised Rs 37,534.65 crore. In 2007, the year before the global financial crisis hit, there were 100 issues worth Rs 34,179.11 crore.

The surge in fundraising in the primary market has come at a time when the equity markets hit record highs on the back of huge investments by domestic investors via mutual funds and foreign institutional investors. The Bombay Stock Exchange's benchmark, Sensex, increased about 27.50 per cent in 2017, hitting a life high of 34,005.37 on December 26. During the year (between January and December 26), foreign investors bought Indian equity worth Rs 49,835 crore, more than double they invested in 2016. Domestic investors, too, invested heavily in the markets via mutual funds, taking the total assets under management of equity mutual funds to some Rs 6.57 lakh crore by the end of November.

“The relative abundance of IPOs in 2017 was due to a combination of factors on both demand and supply side,” said Munish Aggarwal, director, capital markets, Equirus Capital. “On the demand side, we had a very strong performance and unprecedented fund inflows into the secondary markets. On the supply side, this represented a long-awaited opportunity for issuers to provide exit to private equity investors and raise growth capital.”

Interestingly, much of the funds raised went either to the promoters or to existing investors who were looking to pare down their investments or exit completely. For instance, Singapore Exchange, Atticus Mauritius, Caldwell India Holdings Inc and Acacia Banyan Partners sold their shares in the IPO of Bombay Stock Exchange. In the IPO of footwear retail chain Khadim India, promoter Siddhartha Roy Burman and Fairwinds Private Equity sold some of their shares. Bessemer India Capital and Mayfield pared some of their stakes in the IPO of matchmaking website Matrimony.com. The government, too, pared its stakes through several IPOs like that of Cochin Shipyard, General Insurance Corporation and New India Assurance.

Of Rs 65,923.12 crore raised in 2017, Rs 54,793.32 crore was through offer for sale (shares sold by existing promoters and investors) while only Rs 11,129.80 crore was fresh capital raised (funds that went to the companies for their growth plans). “It's a cycle,” said Dara Kalyaniwala, vice president of investment banking at Prabhudas Lilladher. “When the IPO market was not conducive to public fundraising, private equity players, who could understand the risk-reward, had invested in the companies in 2012-2014 period. Today they are making an exit, because one would expect them to sell off when the markets are good.”

It also points to the state of the economy, where existing capacities remain underutilised and, therefore, very few companies are investing in fresh capital expenditures. “The underlying fact remains that new funds are not being raised by companies. This is proof enough that capital formation is not happening,” said Kalyaniwala.

Some experts say things will start looking up as the impact of demonetisation and the rollout of the Goods and Services Tax wanes and earnings growth picks up. “Capacity utilisations across most industries have been below 70 per cent, a key threshold in our understanding for capex decisions. Once the utilisations cross this threshold, managements start contemplating capex and sources of funds for the same. We anticipate that with the twin shocks of demonetisation and GST implementation behind us and relatively strong consumer sentiment, capex growth will come back and corporates will raise growth capital to fund the same,” said Aggarwal.

It is not just the traditional manufacturing companies and service providers that are seeking to raise money now. In a first, a stock exchange went public in India—the BSE raised Rs 1,243 crore in the first mega IPO of 2017. CDSL became the first depository to list on Indian bourses and Reliance Nippon Asset Management became the first mutual fund company to list in the country.

Several insurance companies hit the capital markets last year. State-owned reinsurer General Insurance Corporation raised Rs 11,372 crore in October, making it the largest share sale in the financial services sector. It was also the third largest IPO on Indian stock exchanges. New India Assurance, HDFC Standard Life Insurance, SBI Life Insurance and ICICI Lombard General Insurance were among the other insurance companies that took the capital market route in the year.

While most IPOs did get fully subscribed, not all of them managed a strong debut. For instance, GIC listed on the stock exchange at a 7 per cent discount to the issue price, while New India Assurance listed at a discount of more than 6 per cent to the issue price. “We have seen new funds coming up to participate only in the IPO market,” said Mahesh Patil, co-chief investment officer of Aditya Birla Sun Life AMC, the country's fourth largest mutual fund. “That creates some kind of exuberance and that leads to a kind of aggressive pricing in the IPOs and then there is not much money to be made.”